Up or Out is no longer common in business, except for the cutthroat ranks of management consulting, Wall Street, and Big Law. (And hiring McKinsey’s self-serving consultants, for instance, is often a fatal move for a firm).

For a very long time, up-or-out has been the iron rule of the Army’s very large, but very unsatisfactory, personnel system. It is one of the key reasons it’s unsafisfactory.

Let’s pause for an aside on what “unsatisfactory” means. Nobody likes the system, and everybody tries to fix it. After President Bush (#43) recalled retired GEN Pete Schoomaker to service, the Army’s personnel geniuses (that’s sarcasm) failed to pay him for approximately six months. When they were finally convinced that he wasn’t retired, it’s because they declared him dead and sent all the paperwork that requires to his “widow.” She called his office to see if there was any truth to the matter. (We don’t actually know if “Shoe” ever got paid). If that’s how it is for a serving four-star in the top position, imagine how screwed a private or corporal is when the personnel clerks, who are literally the lowest IQs in the Army, screw up his pay.

After that, Schoomaker vowed to fix the system, and he appointed a guy he knew, a high functioning combat infantry general, to fix it. He did his best, but the system still won in the end. It still employs tens of thousands of low-IQ paper-shufflers, and it’s still completely without accountability, and it still fails. All. The. Time.

One reason personnel is a nuclear disaster in the megaton range is up-or-out. Borrowed, along with many other personnel “best practices” of the day, from the General Motors executive management practices of the late 1920s (!), but up-or-out is no longer common in business, except for the cutthroat ranks of management consulting, Wall Street, and Big Law.

Up-or-out is a reaction to the “retired on duty” problem that was one of the pathologies identified in the thin but brilliant book The Peter Principle by Laurence J. Peter (although the policy in business and the military long predates Peter’s 1950s insights). But instead of leaving someone in position at his “ultimate level of incompetence,” as Peter posits, it promotes everyone to his ultimate level of incompetence and holds him there for two promotion cycles before canning him.

Meanwhile, the need for all officers (and, increasingly, NCOs) to pursue whatever fads are currently driving promotions produces an officer corps where the best are operating under unnecessary and counterproductive pressure and changing jobs before mastery, and the rest are turned into a cade of self-serving, duplicitous, back-stabbing preferment-seekers.

Up-or-out drives dishonesty in evaluation or efficiency reports, in awards and decorations, and in such places as readiness and after-action reports, where an army is depending, in vain, on the integrity of a corrupt process. It becomes a “zero-defects” regime where the rewards go to the best liars and the greatest hypocrites. To the boot-lickers and knob-polishers. To the “leader” who sucks up and $#!+s down on superiors and subordinates respectively.

These personal characteristics are not correlated with leadership ability. Strike that: not positively correlated. Inversely is another question.

Few of the generals and admirals that brought the US (or, for that matter, the UK or USSR) victory in World War II would survive the ruthless culls of their nations’ new personnel systems today. We defy anyone to tell us the present crop of zero-defects zeroes is their equal.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

30 thoughts on “The Problem of Up-or-Out”

You’re spot-on about the zero defects. Since it’s impossible to never make a mistake, an officer looks good by either lying about it or putting the blame on someone else. When you have a careerist officer corps, the career becomes the point of main effort (hey, everyone has wives, kids, mortgage), especially since you don’t get 20 unless you make major (O-4).

Let me also add that right after Desert Storm the armed forces began paying officers to leave. And they let everyone self-select themselves out. The smartest ones with the most viability on the outside looked into the crystal ball and beat feat (I certainly did). The rest got promoted in the 90’s by training (to look good), deploying, and having no incidents while on deployment.

So when we rolled into war in the 2000’s we had a generation of commanders who treated their time in combat as they did deployments back in the day. Get the minimum number of people hurt (or at least not hurt doing anything outside the box), trigger no investigations, wear your reflective belts, and look good until you turn over to the next guy.

Winning the wars didn’t even enter into it. So we lost.

Love the Schoomaker anecdote. Really enjoying this series of posts on personnel policy.

Up-or-out is horrible policy, and you nailed it: it makes the Peter Principle the rule, not the exception. The overall problem is that S-1/HRC (and the one ring to rule them all, budget) drives operations. Key staff members and commanders get added to a battalion a few months before a combat deployment, COs get two years on the nose, not enough time to make any enduring changes, NCOs are pulled out of the operating forces for “broadening tours” lest they be unable to pick up rank. All of this is because the system, heavily driven by up-or-out, prioritizes individuals and careers instead of units and cohesion.

It will take a lot of big brains and serious willpower from the White House on down (and a spiritual son of Sam Nunn or Ike Skelton on the Hill) to fix the military personnel system. Until we do it though, everything else is pretty inconsequential.

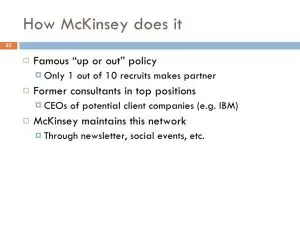

One other benefit of up-or-out to the big consultancies is that consultancies usually treat their alumni very well-e.g. giving them leads for other jobs and good references and such-and use them as an ongoing source of sales leads. So it’s actually beneficial to them to be cycling a large number of folks in and out of their system, and the folks who get cycled benefit from it as well.

With the Schoonmaker anecdote and the ongoing charnel house that is the VA system, I think the military has missed the “treat their alumni very well” part, and last I checked, the politicians were doing a fine job finding countries to screw up without the help of ex-military folks, so I don’t think .mil needs a source of sales leads.

-John M.

I couldn’t possibly agree more. The personnel system hasn’t really worked to the military’s benefit for decades, and service members have paid the price for it.

On my second deployment to Afghanistan, I had a battalion commander who was severely allergic to risk and the possibility of friendly casualties. Needless to say, we didn’t really accomplish much.

I’ve seen a steady succession of senior leaders for the last decade plus who inspired zero confidence in me, both on the O side and the E side.

It’s a rare guy from the WW2 armed forces who would have been able to navigate the system in place today, or would have wanted to.

There is a “New Sheriff in town” General Mattis, Don’t know if he is a member of the up or out school but maybe he has enough brass to bring some organization into the Defense Department. Time will tell and we can only hope for the best and lend as much support as we can to the way it needs to be. Things are moving pretty fast. Better get a good solid (White knuckle) grip for the foreseeable future of not only the military but the country at large.

Good Luck and God Speed USA!

I have to confess to being excited with the new president. He is doing the things I have been preaching about for years. He has a mandate and is beholding to no one. There are going to be a small few who will be hurt or “Run over” by the rapid changes but not as many who would have suffered without them. Hoping for the best.

I thought all that was the point of adopting it by the can’t-cut-its.

And when you force people to lie, and provide perverse incentives for doing so, you can’t be surprised when they take you up on the idea.

The huge flaw is that the only rater that matters is the superior.

Peers and subordinates should get equal say in all ratings, including a go-no go question of

“I would not wish to serve with this officer/NCO/enlisted man, and would recommend they be separated at the service’s earliest convenience//I would wish to serve with this officer/NCO/enlisted man in future, and would recommend they be retained indefinitely to the limits of their utility to the service.”

Throw out the lowest and highest ratings from peers and subordinates, and express the rest as a percentage, including totals (i.e “96% {43/45} of Lieutenant Schmoe’s enlisted men, 90% (18/20) of his NCOs, and 100% (5/5) of his officer peers said they would retain or promote him, and his CO concurs”) would probably give about as accurate a rating of an individual as it’s possible to get without relying on bodycams.

You may be able to snowjob your boss, but you can’t fool all of your people, all of the time.

And while you might get conflicting reports, anyone with a straight up or down, across the board, could be relied upon to absolutely deserve the rating given, in either extreme.

The ones in the murky middle should be reviewed at the lowest level immediately above their rater’s level, and referred to overall promotion/retention boards with suitable recommendations (promote/retain/shitcan).

There should also be gradations of performance, with the average, by command and service absolutely normed at a “C” (Stisfactory). While it would be permissible in any unit to have no one rated above average (“B”) or superior (“A”), no more than 25% and 10% of all personnel, by category, could occupy those tiers, whether down at the company level, the division, or between and beyond those points.

Unlike Lake Woebegone, no more than 35% of your people would be above average. Ever.

And anyone so rated would have to have justification included for the rating, not mere subjective input.

All the “broadening” nonsense should be subordinate to proficiency and excellence in one’s primary field. Anyone with less than 5 years in their direct field should be considered at best a journeyman, and anyone with less than ten years not promotable to senior NCO or officer ranks on grounds of amateur, rather than professional mastery, standing, validated by continued evaluations in that occ field.

“Broadening” should only kick in as a primary concern if they were worthy of retention/promotion to higher levels, once having achieved mastery of the primary duty field.

And there should be some manner of tagging people who are better at command roles, or staff roles, or those rare few good at both, with a view to avoid trying to shove good staff people ill-suited to command at higher levels, or vice-versa, into those positions merely to punch their tickets, after their career midpoint. Some people should be running their strengths, not running an entire organization, and others should be promoting to higher command levels without beating them to death pushing paper and commanding word processors and power points presentations.

Instead, those exceptionally gifted at either endeavor should spend mandatory time imparting the training to do same to the juniors similarly tasked, for the same reason pitchers coach pitchers, and hitters coach hitters in baseball, and not the other way around.

But first off, you’d have to make clear to the organization, probably while simultaneously wielding a whip, chair, and flaming welding torch, that the point of the entire endeavor was building an army that would kick any other country’s ass on command, and not building a gender-fluid eco-friendly Islamic empowerment zone, with transformative powers massaging everyone’s buzzword bullshit bingo splatter-gram of statistical variables, while maximizing budgetary expeditures in pursuit of mediocrity, which is the current paradigm.

This would probably require killing more people outright than were slain at Antietam and Chickamauga.

NTTAWWT.

360-degree reviews are a political nightmare of cartels, intrigue, mendacity and revenge.

And forced-rank systems (and their close cousins, the bell curve) are a political nightmare of mendacity, backbiting, shirking and blameshifting.

360 reviews can be tolerable, but forced rank systems are simply uninhabitable by humans. Anyway by humans who don’t thrive on backbiting and teamicide.

Instead of that nonsense, you need leaders. You know, men who can motivate other men to work for causes above their own narrow interests. You need men who can inspire and provoke integrity and self-sacrifice. You need men who will promote other good men and fire bad ones. You need leaders.

You can read up on Microsoft’s experience doing forced-ranking reviews. It’s reasonably well-documented.

-John M.

Sorry, John, but you’re speaking nonsense, and as if militaries haven’t existed since the dawn of time.

…men who will promote other good men and fire bad ones…

Um, that’s a classic “forced rank system”, descriptive of Roman legions, the Soviet Army, and every other military one could imagine.

And “cartels, intrigue, mendacity, and revenge” are the same problems with the current top-down rated up-or-out system. (cf.: West Point Protective Association)

Or did you imagine military rating officers have their human natures removed before swearing in?

Couldn’t a perma 0-3 or E-5 type fill a reserve or guard spot?

Maybe in a paper-pushing/tech outfit, but not in one where deployability to near-combat was an issue.

Nobody cares about a 50-yr old captain or sergeant in the 217th Mess Kit Repair Company in BFEgypt, but in a unit where you’re running a convoy through Indian territory, and you get ambushed, now you have 50 year old sergeants trying to do fire-and-maneuver.

Anyone who can’t ever grow beyond O-3 or E-5 should be fobbed off on the civilian world, and replaced by some stud who can do the same thing at 20 or 24, and then promote beyond it.

If the Russians ever invade Oklahoma, we can talk about units of Home Guard career low-level types.

Generally, those are your Wal-Mart and McDonald’s assistant night managers and custodial supervisors.

I defer to those with current experience, but anyone unable to promote past E-5 in the current .mil is out at 16 years max; you needed E-6 to get the OK to make 20, and a 50% pension.

As for O-3s, the problem for 70 years is that the .mil has 300-700% of the officers available who could do the O-3/O-4 and higher jobs, and so has purposely de-selected the underperformers, and even the slightly-less-than-absolutely-perfect, because they simply have vastly too many pigs for the number of extant teats remaining at that career point, ever since German and Japanese quality control measures winnowed out the excess company-grade officers prior to 1945.

(Strictly speaking, O-1s and O-2s are mere trainees being tutored by their senior NCOs until they no longer wet themselves in public, and O-3s are the first proto-leaders from that program. O-3s are not in particularly short supply, except in combat arms, at the front, in a shooting war, and under such circumstances, are readily replaced by everything from the brighter O-1s and O-2s down to even E-4s and E-5s, documented many times and places. Such is the business.)

You’re probably right, I was thinking only from my experience and what I think would have fit me. In my area are several grunt reserve units and looking back I would not have minded being a weekend warrior fire team leader at age 30. But it is a big leap to make such low ranks retirement ready and all that.

Any blanket policy, like the “up or out” one, is going to have edge cases where it doesn’t work. There are also places where it does make sense, but that doesn’t really help the ones where these policies are positively inimical.

Sure, a case where you allowed sixty-year old team leaders may net you a younger, fitter cadre, but it also puts you into the position where if you did have a truly superior guy who just wants to be an excellent team leader for twenty years, you can’t do that.

Root problem here is the “one size fits all” mentality, and the fear we have of actually trusting the judgment of leaders at all levels. I say, put that shit in the hands of ghe commanders, and if there are highly competent twenty-year team leaders out there, lrt the commander make the call as to whether or not that guy stays in that slot.

The Peter Principle is a real thing; up or out only institutionalizes it. Balances should be struck, and while you don’t want a unit filled with superannuated geriatric cases in the lower leadership cadre, having a few around to serve as mentors and unit institutional memory ain’t the worst thing in the world, either. Some guys are just on different timelines for professional development, too…

Ding ding ding. The root of the evil is not just up-or-out, but the mentality that says letting a leader hire, fire and promote his own men — you know, like he could if he had the greater powers of a Burger King manager — leads to favoritism and is better supplanted by Soviet style central management. That’s why the Army had 49,000 personnel and pay clerks by MOS last time I looked.

Solution: rate units, or leaders, not individuals, and rate them on one thing alone: performance. And give Commanders absolute hire, fire, promotion and demotion authority.

“Tentpeg, you’re not working out as the first platoon sergeant. Your platoon is always late, light, and last. You were a good squad leader, so you can take a bust to 6 and go to an open squad leader slot in Charlie company, if Captain Queeg will have you, or you can go into the Army Waiver Pool for reassignment. Be grateful I gave you the choice, and maybe you can strike for PSG again when you’ve got more experience.”

“Men of first platoon, meet Platoon Sergeant Kaputnick. We noticed that a whole platoon in Bravo was looking to him for informal leadership, and we thought we’d bring him in here and make it official.”

Precisely so.

Put the power back into the hands of the damn commander, where it belongs.

Hell, as I’ve said before, I think the commander ought to be the guy who passes out the damn goodies at ETS, as well-Do a good job, earn an honorable discharge? Fine; the commander is the guy who decides that you get one, and throws any incidental benefits like extra money for college in.

Thing is, you’d have to have damn good men as commanders, and select them carefully-Or, the whole system would corrupt itself into venal political bullshit in short order.

I’d go farther, and give commanders the ability to add performance incentive pay in every grade on top of base pay.

It would have to be justified by both individual and unit performance, or be reduced/revoked if not justified. But it would give a commander a way to motivate and reward without promotion to a higher grade.

You can’t have a century made up entirely of centurions.

My thoughts on the matter are that there are reasons these things happen, structural ones, and if you want to overcome the problems, you first need to step back and look at the structure of the organization, how it works, and what your actual incentives are, and how they really function, vs. how you have them laid out on your PowerPoint slides.

To my way of thinking, the structured hierarchy we habitually gravitate towards is an invention of the ancients, and is what it is because of the technology they had available to them. The lag in communication also played a role in how we got where we are.

Today, conditions are different than those obtained in the past. The fact we’re still doing business the way we did back in the days of yore, when it took weeks or months to get communications across oceans and continents tells me that we’ve failed to adapt. The structural elements and techniques that grew up in an era when all we had was runners and the post coach worked for a bit, but now that we can do better, we should.

Structured, pipelined organizational hierarchies serve as breeding grounds for careerists and the sort of organizational parasites that create ossified bureaucracies. You want to see how things get done, go observe any newly organized unit that has been put together to solve a particular problem. Done right, such entities are generally filled with adaptable, enthusiastic types who get things done. A good case study would be to take a look at how the First Special Service Force got built, during WWII. Looking at that, and examining the life cycle of that organization, you have to wonder why the hell the lessons from that experience were not taken in and used to build more such units, instead of running the 1st SSF into the ground and then disbanding it. Robert T. Frederick ought to be one of our most studied officers, because of what he did with that mission tasking, and we should have taken the experience as a model for how we do business in the Army as a policy.

Let me be king for a day, and I’d likely take a long, hard look at institutionalizing what Frederick did with that force, and make that the standard manner in which I ran and organized combat units. 1st SSF was something that should have become a prototype for building other units, but that one-off example has never been emulated.

Unfortunately, officers of Frederick’s caliber are rare birds, indeed. The fact that they are is something that really ought to bother the hell out of us, and we should be asking how to make more of him.

Great post. Off to scour Amazon for 1st SSF books.

The 1st SSF is a unit history that deserves a hell of a lot more attention than it gets.

The thing that struck me was that while the Canadians sent a bunch of hand-selected guys, who likely would have been what you’d pick as candidates for any elite unit, the US Army kinda did Frederick dirty, and sent a selection of men that were in some cases straight from the stockade. Not all, of course, but some…

But, the fascinating thing is reading the free-wheeling, entrepreneurial manner in which Frederick and his men went about training and preparing for their mission, which was supposed to be the destruction of the Norwegian heavy water infrastructure. The genesis of the mission started with one Geoffrey Pyke, of Pykrete fame, and Frederick was the guy who was supposed to say “No… Not only no, but hell no…”. Instead, a man who was the epitome of the establishment Army at the time, wound up taking charge of making Pyke’s somewhat poorly conceived ideas and turning them into flesh and steel. The Weasel tracked vehicle, and the 1st SSF were what resulted, and they became such a formidable force that the Norwegians took one look at them, and decided that they’d really rather not have these people running around Norway blowing shit up-Mostly because they were afraid they’d have no shit left to blow up, when it was all over. The unit wound up going into Kiska, and was eventually redirected to the Italian theater where they were used at the Anzio beachhead to cover a division-sized slice of the perimeter. Which they did, and put the fear of God into the Germans.

The whole thing should have been studied in the service schools, and the process by which Frederick took that set of resources and turned it into a devastatingly effective combat unit should have been copied. It’s amazing how often we’ve had these things happen, over the years, and yet refuse to consider the implications for our general organization and operations. The case studies from the British experience with the various “Private Armies”, which wound up producing the SAS and the LRDG in North Africa are also instructive, and things that should be looked at.

If I were to set up a “new model Army”, I’d take a leaf out of the 1st SSF, and instead of having established standing units like we have now, I’d instead work by appointing a commander, who would then work to select and recruit his command team for the mission, and then go from there to stand the force up and train it. If the commander can’t attract the men he needs, or they can’t hack the training? Good sign that that commander can’t do the job, either. If a commander had to actually rely on his own leadership skills and competence to attract men to serve with him for a mission, well… He’s probably not going to do real well at it in theater, either. Our current model basically treats everyone below command level as serfs; you have to work with whatever the Army sends you as a commander, and while that can work… More often, it doesn’t. Were you to structure the entire force on a more entrepreneurial model, from start to finish, you would likely find that lot of your work in terms of assessment and rating has been done for you-If LTC Smith can’t put together a command team, and it’s because nobody wants to work for him, what does that tell you about LTC Smith? With a system like that, the 360 degree rating is built in, and you don’t have to worry about administering shit. “LTC Smith, you’ve been tasked with raising and training a unit from this set of resources… Nobody wants to work with you, because you’re an incompetent, ego-tripping martinet. You’re off the command track, and might want to consider retirement…”.

The Schoomaker case-link in nick goes to a Reuters story from 2013, which is probably worth a post in itself-didn’t actually make his wife call to check if he was dead:

“The letter didn’t cause any undue alarm at the Schoomaker home; the general was living there at the time. He did notice that the letter spelled his name three different ways.”

But since they had STOPPED his retirement checks, without any procedure in place to restart the normal paychecks, the computers did the automatic thing of sending

“a computer-generated letter arrived at his home, addressed to his wife and offering condolences on the general’s death. DFAS’s computers were programmed to assume that when a retiree was taken off the rolls, that person had died.”

One clue to how a COMPUTER generated letter could spell Schoomaker three different ways-“finger gapping” which means pay staff-who don’t type that well, and may not be 100% at actually reading-have to transcribe:

“information from one system onto paper, carry it to another office, and hand it off to other workers who then manually enter it into other systems – a process called “finger-gapping” that Wallace faults as a further source of errors.”

The DFAS computerized pay system was state of the art in 1971 when it was invented. (Seriously-it runs on COBOL.) When the youngish (he was 50) SecDef Dick Cheney put it in use in 1991, it was twenty years old. It’s not getting any younger.

If you ever sit down and talk to the folks who do finance…? At the end of your conversation with them, you’re gonna be astonished that anyone actually gets paid correctly and on time, at all. The word “Byzantine” comes to mind, and I suspect that if they actually ever tried fixing the system in any serious way, they’re gonna crash that sonuvabitch bad. Like, nobody getting paid correctly for significant periods of time bad.

Funniest finance story I know of though, was the one told me by one of the young ladies who I was working near in Kuwait, who had been around the finance block more than a few times. Her description of working at Fort Dix, where they did the final outprocessing for Europe back in the day was… Educational. Per her “There I was…” war story, when she was a brand-new private, fresh out of AIT, she was working in the section that did the finance end of the outprocessing. One day, they get this guy in to send home after 4 years in Europe, and he isn’t in the system. As in, there were no signs he even existed. No accession, and no sign that he’d ever been paid. Ever. Huge red flags go up, mass fear and panic… Where did this guy come from? He’s in every system but the finance one, so how the hell did he get lost?

You can imagine the situation-Everyone came unglued, because they couldn’t find a sign this guy existed or had ever been paid no matter where they looked. No casual pays, no monthly pays, no nothing. He didn’t exist, except that he’s got a full personnel jacket, and he’s in all the other systems.

Investigation ensues, and he’s held over past his ETS date while they try to figure this out. End of the day, what it was turned out to be him getting lost in the shuffle during basic and AIT, never getting into the system, and because he was a green-card resident alien with limited English skills, he never made an issue out of any of it. See, he thought it was like the Army where he and his parents came from, and that he wasn’t supposed to get paid, ‘cos he wasn’t a citizen. His parents had been sending him spending money since day one, and the whole idea that he was supposed to be getting paid in the first place was apparently a huge shock to them all. What was bad was that nowhere along the line did any of his leadership even notice the fact that he wasn’t getting paid, and since he’d never raised any fuss about it, they just ignored the fact that he wasn’t on their finance paperwork (every company commander gets what amounts to a pay summary sheet for his entire unit, and he and the First Sergeant are supposed to screen it for issues). Since our guy got assigned to one of those weird little support outfits that was spread across Germany like thin margarine on rye bread, his leadership wasn’t all that to begin with, and he’d just fallen through the cracks for four years. Four. Fucking. Years.

Yeah, heads rolled.

I think they wound up cutting him a check for something like a couple of grand, when it was all over. I still don’t understand half the shit she was telling me about that case, because I was quite frankly incredulous that such a thing could happen, but her boss the Finance LT that she worked for swore up and down that the whole story was not only plausible, but that he’d heard it when he went through the schoolhouse. From his instructor…

Four years. Dude living on what his parents sent him, thinking he wasn’t supposed to be paid… I can’t even. Where the hell were his squad leader and platoon sergeant equivalents, and how the hell did that get missed for so long?

Very often, the old ways are the best ways. If we still had cash payment – you know, shavetail as pay officer, salute but he doesn’t return it because he’s busy counting money – someone would have seen that this guy was not getting a check to be cashed. However, since everyone was forced to go to direct deposit it would be much less likely to be noticed.

I hope he got more than a couple of grand.

Oh, and the actual lowest GTs aren’t finance; they’re cooks and gun bunnies.

Yeah, this supposedly happened about the time we went to mandatory direct deposit.

Thing that floored me was hearing this story, sitting around in the finance office bullshitting one night, going “No way did that happen…”, and then hearing her boss chime in and say “Yeah, that happened… They used that story at the schoolhouse, when I was up there…”.

In a line unit, that shit would be nearly impossible to have happen-Too many eyes on things at multiple levels, but when you are in one of those TDA-type units, doing support stuff at a remote location…? I can see how it might happen, if the soldier himself never raised a red flag. Hell, I got a guy in from some weird-ass assignment back east, where he was a “one each” guy working with and around mostly civilians and field grades for two years, and the poor bastard was nearly feral. He had never had anyone he worked for even ask him if he had issues, let alone take the time to try and fix them. The day I took him over personally to finance and personnel, after his team and squad leaders couldn’t get traction fixing things, he was in a state of shock. He’d never had the experience of any of his leaders doing their jobs and taking care of him, so after I got done doing my usual “restrained asshole” routine, we finally got a start on fixing his problems. Afterwards? He was pathetically grateful, to the point of tears, and I’m like, “Wait… What? Nobody has ever actually taken your issues seriously, before…? WTF? Who the hell were you working for? Wolves do a better job of taking care of their own…”.

Huge lesson there, for me. Ever after that, with that young man? I could literally do no wrong in his eyes. Due to a miscommunication, and something I failed to triple-check, he and another two soldiers got left out on a ammo guard detail and unfed. I found out about it too late to get them to the mess hall, and wound up having to go buy them fast food. I pull up on the site they were at, and got to listen to him telling the other two soldiers that there is no way in hell that Sergeant K would have forgotten to make sure they got fed, and that something must have happened… Yeah, it sure did; your platoon sergeant is an easily distracted dumbass. Anyway, got ’em fed, all was well, but I had two lessons imparted about things like that: One, once you hook ’em, you’d damn sure better live up to things forever after, and two, it is really an amazing thing how easy it is to get someone’s loyalty just by doing your damn job properly. It is also a huge responsibility, living up to that responsibility, as well.

The troops don’t expect all that much really, at least the half decent ones don’t. The little they do expect anyone ought to be able to deliver. Sad commentary, of course, that many do not deliver.

And it’s not merely laziness; it’s stupidity, too. You’re life will be ever so much fucking easier with troops taken care of and loyal than if you ignore them and their problems. I mean, that shouldn’t be your sole motive, but even a shithead should be able to figure out that that’s enough of a motive on its own. But noooo….

Used to have a part of my in-brief for new troops that, “If you go to the IG over a problem you will make me an enemy for life. Use your chain of command. If they can’t fix it, then come to me. If i can’t fix it I will drive you to the IG’s office and we’ll both throw a screaming fit.”

Never had an IG complaint, interestingly enough.

“Gun bunny” here: true, but false.

I saw both the battalion’s and one arty regiment’s Alpha roster, which included GT scores for everybody in the units.

(Sergeant of the guard gets long and boring, and one will read anything.)

What arty gets, is the leftovers from everywhere else, because they won’t turn them down. Intelligence wasn’t a factor either way. It’s simply that virtually no one asks for field artillery, officer or enlisted, for some decades. If ever.

Some of them assigned are actually stupid, and some anything but.

We had discards from aviation maintenance, band school, MPs, and just about anything else you could name.

But when we had an “old school” section chief who didn’t believe in ear plugs, and tested as functionally deaf after making staff NCO, guess who the new regimental mess sergeant was? Had nothing whatsoever to do with GT, coming or going. (Lack of basic common sense is another story.)

I could have been clearer. I was referring to the minimum required to enlist as a 13B. It was an 85 GT. If it’s gone up, it’s unlikely to be more than 5 points.

Now, some higher quality guys got sent redleg, though not in huge numbers. Friend of mine, also Boston Latin (and we went to IOBC together, too) enlisted the same time I did and went to Ft Polk for IET. I stayed grunt but he got tapped for artillery. His GT was, IIRC, high 130s. Similarly you could find cooks with very high GTs. Not common, but you could enlist for it and the recruiters got credit by ASVAB Cat, not by MOS enlisted for. (And an unsurprisingly large percentage of the high GT cooks were gay. Meh, so what, provided they were good cooks.)

Still, the arty (and spoon) average is low. To me it says something interesting about standardized testing, and that something is not at all favorable, that, low scores or not, Artillery has the best NCOs in the Army. I’ve heard from various jarheads that it’s a similar story there. (I was about to qualify that “best” as “non spec ops” best, but it’s an arguable point how many of modern SF types really are good NCOs. They’re superb human material, of course, but how does one become a good NCO without leading troops? For years? For the _formative_ years?)

Guy lives in the barracks and never leaves the post, eats 3 meals a day at the chow hall, wears his uniform all the time except for special occasions, Parents send him pocket money for haircuts and personal hygene items…

Compared to how he grew up he probably thought he had it pretty good.

Amazing, but I can see it happening.

The guys that didnt habla usualy found each other and helped each other out.

Surprising that one of his buddys didnt notice.

I should have commented on Byzantine. One of the things that correlated very closely with fucked up troop pay is extra pay, be it pro pay, jump pay, danger pay, demo pay, or anything along those lines. I spent a lot of time, circa 1991 and 92, unfucking people’s pay and found that to be a common denominator. I never did pin down exactly why or how the extra bits fucked things up, only that they did.

as someone who entered the Retired Reserve from the CA ARNG with 19 years, 11 months and some very odd days as a SP4/C, i have to laugh at “up or out”…

it’s stupid, non-productive, and, in the face of an utterly broken and/or corrupt promotion system, a fing joke, at best, and a deliberate sabotage of the military at worst.

as i often said over the years, then and now, advancement in any large organization is based on simple physics: 5hit floats, Gold sinks.

(true story: towards the end, they were threatening me with promotion. i LOL’d.)

There was another reason for it, too; namely the tendency for superannuated officers to simply block promotion for years or decades, especially after large wars – the Civil War, the Great War – and large drawdowns.