How about an authentic, combat-deployed, Normandy-captured 88? Yep, the 8.8 CM Flak 36, lovingly and freshly restored by the now defunct Normandy Tank Museum, whose former displays — all of them, apparently — are hitting the auction block next month.

The good news: this is probably the best 88 in the world. The bad news? While it’s offered at no reserve, they expect it to go for €70,000-130,000. There are also a number of tanks and armored, amphibious and soft-skinned vehicles representative of the armies that met in Normandy in 1944, as well as small lots with mannequins and artifacts.

The auction is being conducted by French auctioneer Artcurial; the catalog website is bilingual French-English, there’s a .pdf press release and the catalog (.pdf of course) is downloadable.

The catalog has an excellent précis of this individual artillery piece’s history:

History:

This fine example of a German “Flak 88” was assembled in 1942 by the Bischof-Werke in Sud Recklinghausen using components supplied by a multitude of manufacturers in both Germany and her Occupied Countries.

Here is just a small list of the many diverse companies who sent their output to Recklinghausen for incorporation into this deadly cannon:

- Gunsight optics by Steinheil Sohn of Munich;

- Electrictal system by Merten Gebruder of Gummersbach;

- Gun breech and heavy castings by Schoeller-Blecknaan of Niederdonau and Maschinenfabrik Andritz of Graz, Austria;

- Gun barrel and collar by Skodawerke in Dubinca, Slovakia;

- Electro-mechanical instruments by Siemens Schuckert of Budapest;

- Cable drum holders by Biederman & Czarnikow of Berlin;

- Cable drum reels by Franz Kuhlman of Wilhelmshaven;

- Major steel castings by Ruhrstahl AG of Witten-Annen;

- Bogie winches by VDM Luftfahrtwerke AG of Metz;

- Winch gearboxes by Gasparry & Co of Leipzig;

- Air brakes and fittings by Knorr Bremse, etc.

And of its provenance:

Origin and condition

This weapon has a true Battle of Normandy provenance. It was painted in the standard “Dunkel Gelb” or dark and finish [sic] and supplied in 1942 to a Luftwaffe anti-aircraft division where it found its way to Normandy in early 1943. By June 44, it was positioned in defense of a German Command Center located in an occupied chateau near to Cherbourg.When the Cherbourg pensinsula was over-run by the Allies in July/August, our weapon was captured intact by the Americans who, deciding it might be of some use, painted it olive drab green and presumably had some intention of using it.

As the Liberation of Europe continued, this 88 was left behind and was eventually destined to become a hard target on a firing range. To this end, it was daubed with great splashes of bright orange paint but, thankfully, was rescued after the war by the French Army who repainted it in their own color and who most probably used it for training and educational purposes. After all, it was a very advanced weapon for its day and possessed many innovative technical features.

Finally, our weapon left French military service and passed through the hands of scrap dealers until nally being shut away in a huge barn by an eccentric collector – it has to be remembered that back in the 1970’s there was not a great deal of interest in German WW2 hardware.

And so it languished, becoming covered in grime and dirt until 2014 – all the time the multiple layers of paint ©aking and peeling and ending up a bizarre variegated hue. The Normandy Tank Museum rescued the weapon and placed it in the hands of their highly experienced German restoration expert who, over a period of 8 months, brought the sad relic back to the amazing condition one sees today.

Missing or badly damaged parts have been replaced with locally sourced original replacements – an example of which was a set of the 3 part “Trilex” wheel rims and locking ring which our restorer found amidst a load of farmer’s scrap dumped in a forest when walking his dog.

The 4 brand new wheels and cartridge cases came from the Finnish Army who used them as practice rounds up till the 1980’s. They are obviously empty but, interestingly, are dated June 1944. The fuse nosecones are 3 anti-aircraft and one anti-tank. So a weapon with true Normandy provenance and a major rarity these days as many of the surviving and displayed “88’s” are of Spanish origin. This cannon is one of true German manufacture- a fact which adds significantly to its value.

The 88 was a revolutionary gun and its carriage, in particular, was copied not only by larger German AA guns used for homeland defense against the Allied bomber offensive (in 10.5 and 12.8 cm flavors), but also by American and Soviet AA gun designers.

Silenced Enfield Obrez…? Uh, no.

Hey, what’s this? We found it on a Russian forum, and it almost looks like a suppressed version of one of those cut-down Mosin “Obrez” sawn-offs used by various Russian mischief makers. But that can’t be what it really is. Where would Russians get a Lee Enfield (well, apart from any left behind by the Allied intervention in Archangelsk 1918-19)?

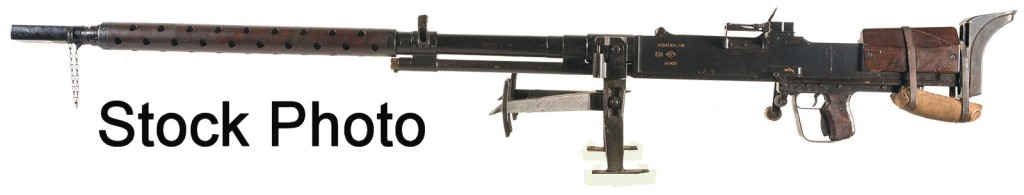

A pre-World War I vintage “Sht. L.E. III” which breaks out to “Short Lee Enfield Mk III,” it says here:

It has a King’s Crown and the cartouche ER, of Edward VII, who was King and Emperor in the first decade of the 20th Century. (He was succeeded by George V, King during the First World War).

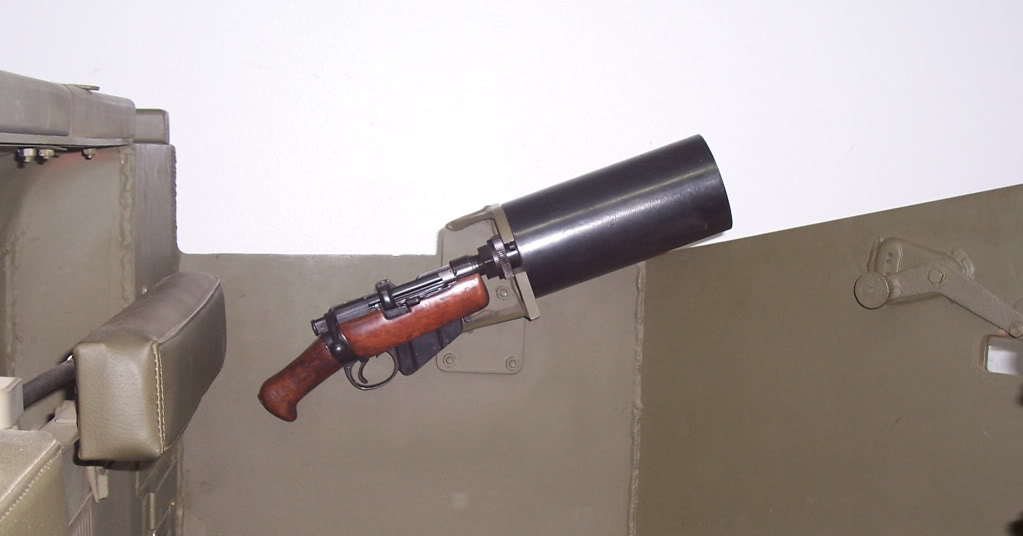

It even looks a little like a suppressor if you take it down:

But we’ll let you in on a secret — the muzzle end is wide open, like the X Products “Can Cannon.” That’s a clue. Know what it is yet?

Here it is in place, wrapped up:

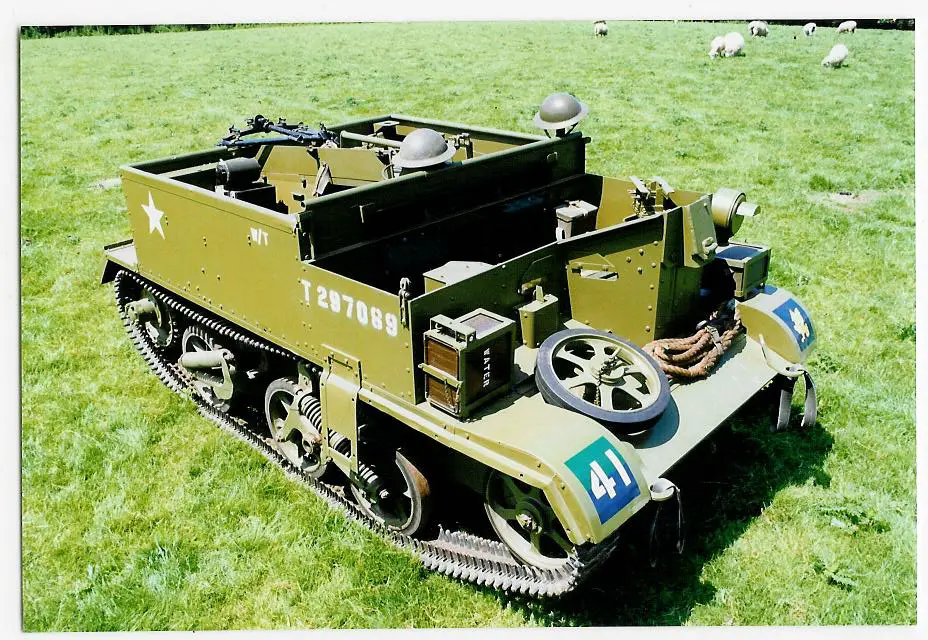

It’s a grenade launcher for the light Universal Carrier, aka Bren-Gun Carrier, a tiny armored vehicle much used by British and Commonwealth forces and descended from the flimsy Carden-Lloyd light tanks of the 1920s. The launchers were meant to be used with blanks only to fire (as far as we know, only smoke) grenades. Depending on the Mark of the Carrier and where it was built, this launcher might have been built on any available .303 action — Enfield, Ross, or even Martini. Here’s a Martini one in context:

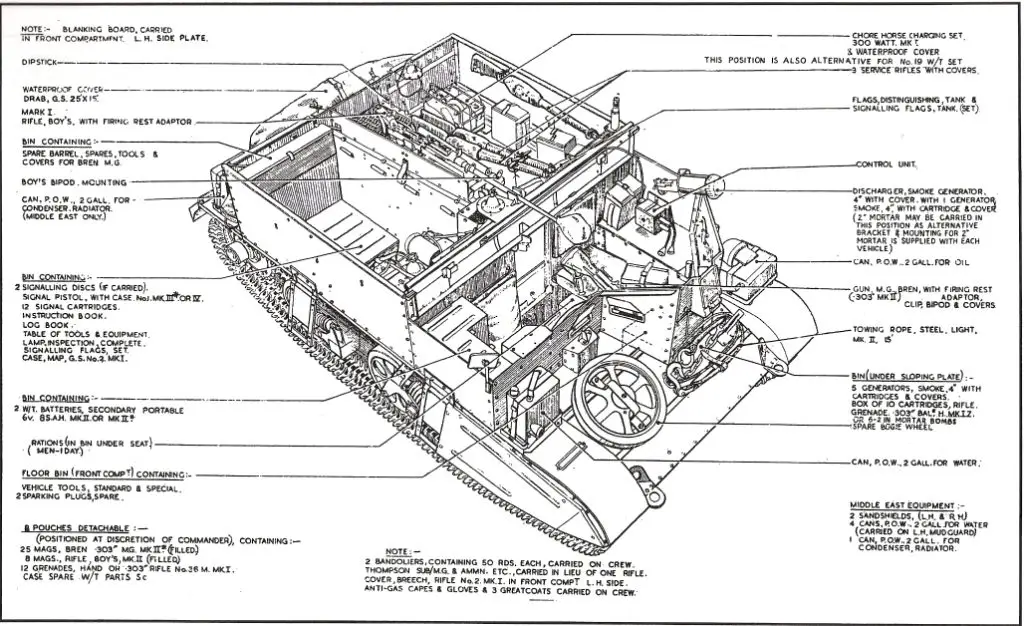

Yes, the Bren gunner or TC served this launcher from the left seat, whilst the driver jockeyed the vehicle from the right (even in the Canadian models, made in vast quantities by Ford of Canada and still occasionally turning up rusty in a Saskatchewan wheatfield). This sketch shows you where it all goes in the Mark II carrier (this one set up for a Boys 0.55″ Anti-Tank Rifle crew).

It was a tight fit for several men and all their kit in this tiny armored fighting vehicle, and it was at the mercy of nearly anything the Germans or Italians chose to fire at it. But you go to war with the Army you have.

Puts British and Commonwealth nerve in a bit of perspective, to think of calling this “armor.” It’s at the very bottom of the mechanized war food chain.

Here are a couple of pictures of restored carriers. The firearms and helmets should give you some idea of the scale of these toy poodles of the tank world:

After the jump, two videos of running carriers: one enthusiastically driven (he actually drifts a curve), and the New Zealanders Motor Vehicles Collectors Club in 2015, breaking an Aussie record for most running carriers at a display!

Continue reading

Paratroops vs. Tanks, 1945

The little-studied and nearly forgotten last airborne operation of World War II, Operation Varsity, eventuated along the Rhine River on March 24, 1945. The participants had no way of knowing it, but they were six weeks from V-E Day and the end of the War in Europe. That end happened for many reasons, in part because the Western Allies forced the Rhine in March. (But had the Allies been held or thrown back, the Germans still would have lost, because the Red Army was coming from the East in any event).

Both sides came to the Rhine fight with Operation Market-Garden in Holland and Unternehmen Wacht am Rhein (called “The Battle of the Bulge” by the Americans in its path) in the Ardennes fresh in mind. One was an Allied fight, one a German, but both were ambitious offensives that fell far short of their goals. The American division that would be tabbed for Operation Varsity, the 17th Airborne, had come in at the end of the Bulge to hold the cleared salient to Bastogne open, and to push the Germans back. They knew what fighting against German armored counterattacks would be like. The Germans holding their side of the river knew that the Allies had as many as four paratroop and glider divisions opposite them, and they knew just how weakened their units were by the endless meatgrinder of combat (one division was down to 4,000 men, counting walking wounded; that was about what the 17th was short after the Ardennes casualties, but the American unit got replacements).

One thing everybody knew: paratroops were overmatched by tanks. The Germans expected the Allies to land by night and planned to crush them by tanks at first light. The paratroops knew they needed to kill tanks. The problem was: it takes a hard hit by a heavy shot to kill a tank, and things that fired hard-hitting heavy shots tended to be bulky and heavy — not something you could jump out of a C-46 or C-47 with.

In the Ardennes, along Dead Man’s Ridge northwest of Bastogne, a paratroop sergeant named Isidore Jachman had engaged a German tank formation with the only organic AT weapon the airborne infantryman had, the 2.36″ (~60mm) Rocket Launcher (aka Bazooka).

Jachman engaged two tanks, killing one and forcing a German retreat, but enemy fire killed Jachman, who became, posthumously, 17th’s only Medal of Honor recipient prior to Varsity. His citation:

For heroism January 04, 1945 at Flamierge, Belgium. When his company was pinned down by enemy artillery, mortar, and small arms fire, two hostile tanks attacked the unit, inflicting heavy casualties. Staff Sergeant Jachman, seeing the desperate plight of his comrades, left his place of cover and with total disregard for his own safety dashed across open ground through a hail of fire and seizing a bazooka from a fallen comrade advanced on the tanks, which concentrated their fire on him. Firing the weapon alone, he damaged one and forced both to retire. Staff Sergeant Jachman’s heroic action, in which he suffered fatal wounds, disrupted the entire enemy attack.

57mm and halftrack prime movers.

The AT armament of the paratroops would be carried by gliders. By 1945, the inadequate 37mm gun (called by the British the two-pounder) was retired and the standard gliderborne airborne-unit AT gun was the 57mm, a good weapon for 1941 but hopeless against 1945 main battle tanks; the British users called it the six-pounder. (British and American guns had different carriages but the same tube).

In other American units, the prime mover for the 57mm AT was a half-track or a 1 1/2 ton Dodge 6×6 truck. The glider units had to make do with jeeps as prime movers. Carrying a sufficient ammo supply was a problem, and the gun and the jeep each needed their own Waco or Horsa glider.

An American AT gunner in another unit remembers this weapon:

My platoon was three 57mm Anti-Tank guns. A squad of 10 men for each gun. This gun was a reworked British “6 pounder”, so called because it fired a 6-pound projectile. Our version had good ballistics. A muzzle velocity of about 3000 fpm. It would penetrate 2 inches of armor plate and ricochet with killing velocity about 50 times. It sure didn’t look very impressive. The gunner had to kneel or sit to look though the sight.

A British 6 pounder (57mm) showing the crew’s kneeling position.

His crew got a lucky hit on a Panther that let them barrage the tank and drive the crew out of it.

We had gotten our kill! That hole in their defense had to be covered by adjoining Panthers. Later a Bazooka team got another one. … At least we were no longer kidded about our “Little Pea Shooter”. Most didn’t consider the 57mm much of a weapon.

The 57 had definite limits when engaging modern tanks. But it was far more accurate and longer-ranged than the bazooka!

British forces had another option. Two batteries that airlanded on Varsity had three troops each with 6-pounders and one with 17-pounders. The 17-pounder was a high velocity 76.2mm weapon. This was, much more than its 6-pounder sibling, an effective AT weapon, but it was a lot bigger — by the time it, and its crew and prime mover were all lined up, it was a 17 thousand pound logistical nut to crack. They could only deliver these by the gigantic General Aircraft Hamilcar glider. And glider delivery was always risky. Two Glider Pilot Regiment Sergeants, Peter Young and Neville Shaw had one of these heavy guns in a Hamilcar that didn’t get off its departure runway. Young:

Our load was a 15-hundredweight truck and a 17-pounder antitank gun, with a crew of eight soldiers, 70 rounds of ammunition, and spare petrol. The total weight was around 17,800 pounds.

We have the distinction of completing the shortest flight. On take off, the Halifax [tow plane] got into a tangle in the slipstream of the aircraft in front and cast me off. There was no choice but to put down in the overshoot. There was a spare loaded glider, but it was decided not to use this.1

Shoulder patch of the now-forgotten 17th

Airborne Division.

In the American forces, there was no formal anti-tank organization, unlike the British unit’s. Instead, the 17th’s 155th Anti-Aircraft Battalion picked up anti-tank duty, and the weapons to go with it. (This may have been because of the weakness of the Luftwaffe by March 1945). Oddly enough, the unit had a mix of British 6-pounders and American 57mm, but since the tubes and ammo were the same, the mixture had no practical effect.

But a new wonder weapon came to the battalion less than two weeks before showtime: the 75mm Recoilless Rifle.

Exactly two of these newfangled gadgets replaced six-pounders, one in each of two batteries. One of the crewmen, Corporal Eugene Howard, remembers:

It looked a lot like a fancy bazooka. It had a 7 foot long rifle barrel mounted on a yoke, with a pin on the bottom of the yoke to fit onto a .50-caliber machine gun tripod. The rifle weighed about 175 pounds and the tripod weighed about 65 pounds.

The gun was fitted with a new electronic sighting device that made it more accurate than the sight on the 57 mm [recoilless rifle]. In one respect it was like a bazooka: when the gun fired, a blaze of hot gases came out the rear of the gun with an equal force to the projectile coming out the muzzle. It had an effective range of about 1,500 yards.

The jeep was modified to carry the gun. The tripod mount was secured to the floor of the back section of the Jeep. A cradle for the barrel was welded to the front bumper of the jeep. One of the advantages of the gun was that it could be fired from the jeep. It could even be fired with the Jeep moving. Since we did not have to pull the 57-millimeter we would get a jeep trailer to haul ammunition. This meant we could haul more ammunition than we could for the 57-millimeter.2

Howard found the 75mm recoilless rifle worked well. The first time they were called on to use it, they killed a “self-propelled 88” (probably actually a 75mm StuG-III). Then they got the jeep into defilade, and began running the 75 against German vehicles, troops, and even an OP in a church steeple.

But that’s another story. What Howard and his gunner Pete found out was that the 75mm was an effective tank buster, within its limits, and they set a trend in paratroop AT weapons that lasted until the missile age. (Indeed, Russian and Chinese factories still produce much improved, larger caliber lightweight recoilless rifles).

Notes

- Wright, p. 68.

- Wright, p. 9.

Sources

Wright, Stephen L. The Last Drop: Operation Varsity, March 24-25, 1945. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2008.

Why Were Cannons Bronze?

This Bronze 1857 “Napoleon” is a Steen reproduction. They didn’t shine like this in field use!

Long after the Bronze Age was over for swords, knives and pole-weapon heads, the prehistoric alloy was still used for cannon. Why?

Because while iron and early, uneven-quality steel were fine for contact or melee weapons, they weren’t a sure thing for containing the violent deflagration of gunpowder that launches cannon projectiles towards one’s enemy. Bronze could be cast and machined with high consistency.

It turns out that this question has already been studied at length — and we’ll quote from a 2002 thesis by Chuck Meide at the College of William and Mary. (The whole thesis will be attached at the end of this post as a .pdf. It’s full of gems like this).

Writing at the end of the muzzle-loader era, British artillery officer Manley Dixon in 1858 summed up nicely the required material qualities necessary to create ordnance:

The material should be hard, so as not to yield too easily to the action of the ball when passing out of the bore; tenacious, so as to resist the explosive power of the Gunpowder and not to burst; and lastly, elastic, so that the particles of the material of which the Gun is composed should, after the vibration caused by the discharge, return to their original position (McConnell 1988: 15).

Bronze and iron were the only two metals with these requisite qualities available to historic gunfounders, and bronze was long considered the superior metal for ordnance manufacture. Up until the third quarter of the sixteenth century, however, iron guns outnumbered bronze pieces, though the former were almost all wrought iron, of decidedly inferior quality. The most powerful guns had to be cast, not hand-wrought, and as cast iron guns were overly heavy or dangerously unreliable, bronze was the material of choice throughout the 16th century. Though Henry VIII’s Mary Rose (wrecked in 1545) displayed a marked diversity of bronze and iron ordnance (Guilmartin 1994: 148) by 1569 the decision was made to equip Queen Elizabeth’s navy entirely with cast bronze guns (Lavery 1987: 84).

The main disadvantage of bronze guns was their price, which was generally three to four times higher than iron guns (Cipolla 1965: 42). In 1570 England, iron ordnance cost £10 to £20 per ton while bronze cost £40 to £60. With improvements in iron casting techniques, the price of iron began to fall by the turn of the century, and the difference in cost began to steadily increase, so that by 1670 iron cost only £18 per ton, while bronze cost £150 for the same amount (Lavery 1987: 84). As the principle maritime powers continued to increase the size of their navies in the 17th century, this cost became prohibitively expensive. An example, to put this greater cost in perspective: the four small bronze cannons carried as cargo on the French ship La Belle (wrecked in Matagorda Bay, Texas in 1686) cost more to manufacture than did the entire vessel! (personal communication, John de Bry, 1996)

Not surprisingly, rulers in the first half of the 17th century began to mandate and subsidize experimentation in iron gunfounding, in order to improve the quality of iron ordnance. Other than expense, however, bronze guns were still superior to iron ones in almost every way. Bronze was stronger, withstood the shock of discharge better, and lasted longer at sea. Bronze also was easier to cast, could be re-cast, and could be easily embellished with decoration. Because of this last quality, along with their hefty price tag, bronze guns also served as status symbols, an aspect whose importance should not be overlooked in the 17th century, when capital ships represented not only the might but the prestige of the king.

Despite the fact that bronze is 20% heavier than iron, bronze guns were lighter than their counterparts because the stronger metal could be used to make thinner guns of the same caliber (Tucker 1989: 10). The dramatic weight differences between bronze and iron guns of the same caliber are illustrated in Table 1 (keeping in mind that a gun of the same size and metal could vary by as much as 2-3 hundredweight or 224-336 lbs) (Tucker 1989: 10). The reduced weight of bronze ordnance was particularly important for field artillery.

| Gun Size | Bronze Guns | Iron Guns | ||||||

| Length | Weight | Length | Weight | |||||

| shot weight | feet | cwt | lbs | kg | feet | cwt | lbs | kg |

| 42-pdr | 10 | 66 | 7392 | 3356 | — | 75 | 8400 | 3814 |

| 32-pdr | 91⁄2 | 54 | 6048 | 2746 | 91⁄2 | 57 | 6384 | 2898 |

| 24-pdr | 10 | 46 | 5152 | 2339 | 91⁄2 | 49 | 5488 | 2492 |

| 18-pdr | 91⁄2 | 40 | 4480 | 2034 | 91⁄2 | 42 | 4704 | 2136 |

| 12-pdr | 91⁄2 | 31 | 3472 | 1576 | 91⁄2 | 36 | 4032 | 1831 |

| 9-pdr | 9 | 28 | 3136 | 1424 | 9 | 30 | 3360 | 1525 |

| 6-pdr | 9 | 19 | 2128 | 966 | 81⁄2 | 21 | 2352 | 1068 |

Table 1. Comparison of the weight of bronze and iron British naval guns, ca. 1742. Adapted from Gardiner1979: Table 8. Original source, undated table in British Admiralty records (ADM 106/3067). “cwt”=hundredweight, or 112 pounds.

One especially salient advantage was that bronze guns were less likely to break while firing, and when they did the barrel usually bulged or split open longitudinally at the breech rather than explode. When iron cannon burst they tended to shatter and fly to pieces, which caused much more catastrophic damage to nearby personnel (Tucker 1989: 10; Kennard 1986: 161; Guilmartin 1983: 563). Figure 7 illustrates the striking difference between two failed guns, one of bronze and the other of iron. Improved iron casting techniques and gun design, however, would help solve this problem, though the reinforced guns had thicker metal at the breech and reinforces, increasing their weight. While iron guns were never considered as safe as bronze pieces, by the 1630s both England and Sweden were exporting iron guns of reputable quality (Cipolla 1965: 43; Kennard 1986: 161).

Figure 7. Two guns, one bronze and one iron, that have catastrophically failed (burst). The upper gun is a bronze 6-pdr, cast by Richard Gilpin in 1756 (526 lbs/238.8 kg, 4’ 6”/1.372 m long). This English gun burst at St. Lucia in 1783, tearing open longitudinally at the first and second reinforces. Currently housed at the Museum of Artillery Rotunda, Woolwich, from McConnell 1988: Figure 15. The lower gun is all that is left of an iron cannon that exploded, with massive loss of life, while firing on English troops invading St. Augustine on 10 November 1702. Photograph by the author.

The sole disadvantage of bronze as a gunfounding material was its propensity to heat up quickly, which meant that when firing a great number of shots in continuous action it was prone to becoming soft and susceptible to sagging or other bore damage (McConnell 1988: 15). Due to the nature of 16th and early 17th century naval tactics, however, this defect was not readily apparent; by the time of the great broadside to broadside slugfests of the 18th century, ships had already exchanged their bronze guns for iron ones. It would not be until the sieges of the Peninsular campaigns of the early 19th century that this defect became widely known (Kennard 1986: 162; Fisher 1976: 279-280).

What caused bronze to finally lose its throne? First came some centuries of technological improvements, which had English and Swedish gun makers producing solid, safe iron naval guns by the time of the American Revolution.

Terrestrial artillery was another matter. Bronze first was replaced in large siege guns in the early 1800s, but the weight advantage kept bronze 6-pounders and mortars in the field for the British Army in the 1850s and 60s respectively, and the US didn’t give up the smoothbore 12-pounder bronze Napoleon until long after other armies had done so — until the 1880s, in fact.

The thesis covers all this and more (including what all the confusing traditional names for muzzle-loading bronze artillery, such as culverin and falconet, signify).

Meide2002_Bronze.pdf

What’s Cooler than a Suppressed FN SAW M249S?

What’s Cooler than a Suppressed FN SAW M249S? Well, how the same gun plus Jerry Miculek? Yep, we’re talking about Louisiana’s fastest-shootin’ son, king-hell competition and exhibition shooter Jerry Miculek, yielding a suppressed semi SAW, popping silhouettes at a few meters.

As God is our witness, if we had to face three bad guys that close with only a SAW, when we got finished distributing the 216 virgins, we’d then weld a bayonet lug on the gun.

For next time, you know?

If you can’t see it here you can probably pick up the movie on YouTube.

We’ve wanted one of these SAWs since FN announced it, and this video does not make us want it any less. It looks like they’re shipping now — at least, to reviewers.x

More AT Rifles for Sale

If you missed last week’s Boys Mk.I., that’s OK, there are other anti-tank rifles on the market. Just the thing for when “they” come, although to be sure these haven’t been tested against flying saucers.

Collector weapons dealer Bob Adams (whose long dark night of ATF persecution seems to be over, in his favor) has several Anti-Tank Rifles for sale at the moment.

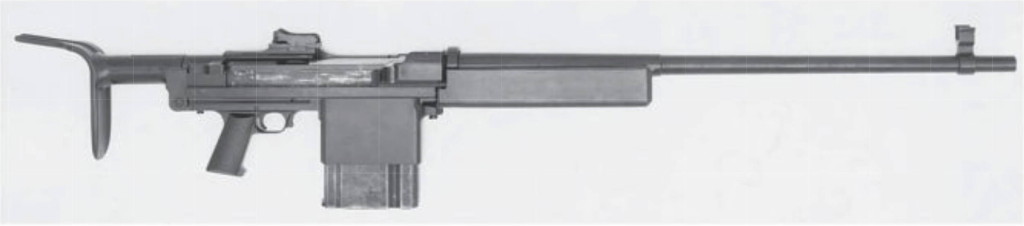

I: 20mm Lahti Semi-Auto: $10k

The first is a registered 20mm Lahti Model L-39:

Bob writes:

Description and pictures to follow shortly. This is a live destructive device requiring a $200 transfer tax. It has a Russian Heavy Machine Gun (DShK) tripod adapted to it by the Finns during WWII. The tripod alone is rare.

All he has at the moment is the stock photo and a picture of such a weapon in use by the Finns.

II: 20mm Solothurn M/39 Model S-1000 Semi-Auto: $12k

This is the Lahti’s Swiss cousin.

Bob says:

This was recently deactivated by drilling holes in the barrel. It can be re-activated by replacing the barrel and filing a Form 1 with ATF or rebarreled (or sleeved) to .50 BMG with no ATF registration.

We’re kind of doubtful a .50 x 99 conversion would be quite that easy, but people have done it.

Finally, we get to the king of beasts, historically speaking:

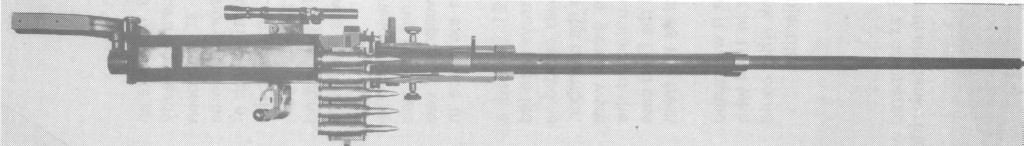

III: 1918 Mauser T-Gewehr: $10k with .50 BMG barrel and original barrel.

This is the original, single-shot, bolt-action Mauser anti-tank rifle, the gun that inspired the .50 Browning cartridge and machine gun. It’s set up as a shooter, but no irreversible alterations have been made to this historic piece.

The .50 barrel is mounted. The inset shows the original 13 x

Rare Mauser Tank-Gewehr 13mm WWI Anti-Tank rifle with extra .50 barrel. Rare and historic German military anti-tank rifle made in 1918 by Mauser to defeat early tanks. All matching and complete with original bipod. Very good condition with much blue & some brown patina. Very good or better original bore which can be improved. Excellent .50 Browning 45″ barrel w/scope rail installed on barrel for shooting. Original parts unaltered and complete with the original barrel! Note: ATF has ruled these are not a destructive device.

This is a close-up of the single-shot breech and the sturdy scope-mount rail as installed. As you can see, it attaches to the barrel, leaving the receiver unmarked.

Of these, in our opinion the one with the greatest historic significance and the best potential for appreciation is the original T-Gewehr. But all these guns are priced in Barrett territory, which makes them (in our opinion, for whatever value you may give that) underpriced.

Want to Own an Antitank Rifle? Here’s a Boys!

Maybe you’re going to get a tax refund in the low five figures (if so, you need to adjust fire on your withholding or quarterlies, but roll with us here for the sake of entertainment, will you?) Let’s take a quick survey of the market for original anti-tank rifles, shall we? This will be Part 1 (because we got 1200+ words out, describing the rifle that was going to be half of the original post).

Boys .55 AT Rifle, British Design, Made in Canada 1943.

Skip Edgley in Maryland, whom we don’t know personally, but with whom we think we’d get along famously, is selling a Boys .55 Anti-Tank Rifle as made by the Canadian wartime gunmaker John Inglis & Company, marked “US Government Property” like a US Military firearm. It comes with three original mags (which come up for sale from time to time) and 200 rounds of original ammo (which is much less common).

Yes, it’s a big beautiful doll of a weapon. Pretty much a lock that it will not fit in your existing safe. It’s a rare bolt-action, magazine-fed AT Rifle.

The sights are offset left to clear that enormous magazine:

And a lot of attention was paid to recoil management:

Here’s his description:

Up for bids is a British Boys Model RB MKI .55 caliber bolt-action Anti-Tank Rifle with bipod. Excellent condition, totally functional. All serial numbers match. Total of 200 original rounds, 40 sets of 5 rounds in stripper clips/bandoleers in two original wooden crates, one full and one partial. DO THE MATH! 1939 dated, original British made .55 caliber ammo is selling (WHEN YOU CAN FIND IT) for around $50.00/each. That’s $10K in just the ammo. That makes the gun cost $2K. This rifle is complete with the original front mounted bipod, three original magazines and the original muzzle break. The magazines are an original WWII British issue. Condition is excellent with 95% of the original wartime finish which has darkened from age, showing only minor edge and high spot wear overall. The bolt body retains its original factory bright finish and the various parts all show their original British proofmarks. The supple cheekpiece, front and rear pistol grips still show their original wartime finish. This is an excellent, all original example of a desirable WWII British/Canadian manufactured, U.S. Army issue Boys Anti-Tank rifle. Manufactured by Inglis of Canada.

These were bought by the United States, not for the US Army, but for Lend-Lease purposes, for Commonwealth forces and for China. As they were quickly obsoleted by improving Axis armor (and improving Allied infantry AT weapons)

This beautiful Anti Tank Rifle was designed and manufactured in Canada for the British and Commonwealth Armies. It is the most powerful rifle ever issued to any modern army. It was the infantry Anti Tank weapon of the British Forces in France and, at Dunkirk, helped to stave off the attack in the German Panzer forces, to permit the evacuation of the Allied forces. It was again prominent in holding intact the British defenses covering Egypt and the nerve center at Cairo”. The Boys Anti Tank Rifle weighs 33 lbs (including bipod) and is 63 inches long. Has three, five shot magazines in an original steel magazine box, muzzle brake, and a thick and soft recoil pad.

Gun is in MD on a Form 4. Curio and Relic. $12,000.00.

One of the reason we like Skip, even though we don’t know him, is his sense of humor (bold emphasis below is ours):

My hi-def close-up photos are part of my description. They are not taken from the Hubble or even a foot away. They might show imperfections that may or may not be apparent to the naked eye. They may also show reflections and some dust/lint that will not be included with your purchase. Please examine them closely. I attempt to list ALL imperfections in my description. Shipping includes insurance. AK & HI slightly higher. My email will not accept mail through the GB board. Please contact me directly at [email protected] Plastic +3%. NO RESERVE! Thanks!

via Boys Antitank Rifle 55 Cal MKI DD WWII British : Destructive Devices at GunBroker.com.

Starting bid is $12k; because it’s > .50 caliber, this is a Form 1 Destructive Device and needs an ATF transfer. (If you’re diffident about owning an enormous AT rifle chambered for a bizarre caliber obsolete for 80 years, he’s also got a bargain-priced ($6500) Stemple Sten that will transfer on Form 1, Form 3 if you’re an appropriately-licensed SOT of course).

More pictures of the Boys Rifle are after the jump at the end of the market survey!

Coming soon (hopefully Monday!): More Vintage AT Rifles!

Bob Adams has resolved his long battle with the ATF (entirely in his favor, it seems; the ATF decided to make an example out of him for being an FFL dealing with non import marked pistols, which is perfectly legal, and, mirabile dictu, the courts followed the law). Why does this matter here? Because, along with his usual high-end collector pistols, he has a treasure trove of anti-tank rifles for sale, including some examples that even the advanced collector seldom sees. Look for them RSN (Real Soon Now®).

Click More for (duh) More!

Once again, the “excess” pictures are after the jump, for the lover of AT Rifle porn.

Continue reading

Japanese Infantry Anti-Tank Weapons of WWII

Recently we’ve been talking about AT Rifles. The biggest that were deployed were the semi-auto Solothurn (used by Germany and Hungary), the comparable Lahti (Finland), in 20mm, and the daddy of them all, the 20 x 125mm Type 97 of Japan.

Recently we’ve been talking about AT Rifles. The biggest that were deployed were the semi-auto Solothurn (used by Germany and Hungary), the comparable Lahti (Finland), in 20mm, and the daddy of them all, the 20 x 125mm Type 97 of Japan.

You don’t hear much about Japanese anti-tank warfare. In part this is because, by the time Japanese forces were about to fight Allied tanks, they were logistically starved, down to eating tree bark, and, in some of the last island campaigns, their own and American dead.

The 1200 Type 97s made were scattered across the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. You couldn’t count on a supply of special anti-tank ammunition. Anti-tank tactics, for the retreating Japanese, involved infantry swarms on isolated tanks, or use of anti-tank artillery or general purpose field guns in direct-fire AT engagements.

The Russians had already encountered (and captured) some of these weapons in the fighting at Khalkin Gol in the so-called Manchurian Incident in 1939, so they knew what to expect when they declared war on Japan in 1945. The US on the other hand did not see the weapon until late in the war (we believe, in the Philippines).

The Type 97 was a real beast, weighing 50 kilograms empty (110 lbs). There is some irony in the nation with the smallest soldiers producing the largest anti-tank rifle. The Japanese Army had a clever solution — handles clipped on to the rifle that let four men carry it, like stretcher bearers (a similar approach was used to handle heavy machine guns).

Type 97 AT Rifle with handles (image from world.guns.ru).

The gas-operated semi-auto rifle was fired from a bipod attached to the gas tube and a rear monopod attached to the forward end of the buttstock. It used a locking wedge to hold a bolt and carrier together initially on firing. We’ve never seen a photo with an optical sight, but there must have been one; Japan made superior optics even then, and many Japanese MGs were fitted with optical sights so it stands to reason the AT rifle would have had them.

By 1944 the AT rifle was a no-hoper in terms of engaging American tanks. But Japan’s ally, Germany, came through with samples and drawings of the Panzerschreck aka Ofenrohr anti-tank weapon. Essentially it was the US Army’s 2.36 inch rocket launcher, scaled up to 88mm bore (about 3.5″) and capable of a frontal-armor penetration and kill on most world tanks.

Japan made a modified copy of the German AT rocket launcher, which they called the Type 4 Anti-Tank Rocket Launcher. The firing mechanism was a direct copy, and the rocket and warhead were very similar, albeit scaled down to 75mm.

The tube was a meter and a half long (1525mm, or 61″). Fortunately, the unwieldy tube broke down into two halves for carrying. Crew drill and firing positions were very similar to that of the American or German counterparts, although the Japanese provided a bipod like the one on their light machine guns. The sighting system was rudimentary: a rear peep sight and two front posts, one over the other, the upper post for 50 meters and the lower accounting for the rocket drop at 100 meters. The sights were welded to the left side of the tube and protruded about 2 inches to the left; the gunner took the left side and the loader the right of the weapon. As with any rocket launcher, the backblast was hazardous and the launch signature made the area of the launch a magnet for enemy suppressive fire.

This weapon, had it been issued in quantity, might have been problematic for American (and once they joined the war on Japan in the summer of ’45, Russian) tankers, except that production of the system began very late, and very few were produced (perhaps only hundreds). Those that were produced may have been retained for defense of the home islands, a defense that was canceled by the unconditional Japanese surrender to the Allied Powers. A Honshu defender who had a Type 4 was well equipped indeed, as many of his fellows had nought but lunge mines (which are exactly what they sound like) or bamboo spears. Still, he would one of millions of lives saved by the nuclear bombing and resulting cancellation of the invasion, and is probably a lucky man that he never fired a Type 4 at an American tank.

Sources

Natzvaladze, Yuri A. The Trophies of the Red Army during the Great Patriotic War. Mesa, AZ: Champlin Fighter Museum, 1996.

Popenker, Maxim. Type 97 anti-tank rifle (Japan). World.guns.ru, n.d. Retrieved from: http://world.guns.ru/atr/jap/type-97-e.html

Another American Anti-Tank Rifle — Wait, Two of Them!

No sooner had we written that the T1E1 Anti-Tank Rifle of 1940-44 was “the only US AT Rifle” when we saw another AT Rifle mentioned in passing in a very interesting Bruce Canfield article on Winchester’s Light Rifle. (Hat tip, TFB). We got the notion to look it up and found this AT Rifle… but, while it’s a Winchester Anti-Tank rifle not the one Bruce mentioned. He referred to a WWII rifle that was a scaled up version of David M. Williams’s short-stroke gas-piston action. This is a WWI bolt gun, and a strange one it is.

The Winchester Pugsley .50 AT Rifle

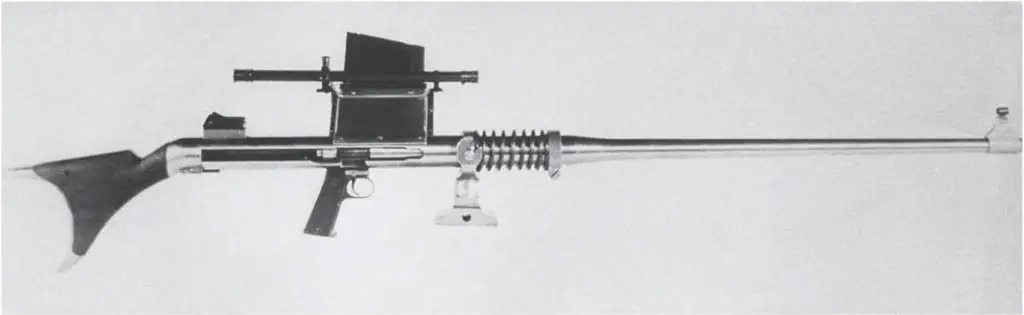

The gun in the photo (which comes from Houze’s Winchester Repeating Arms Company, where this oddball is briefly covered on pp. 189-192) is clearly not a finished work, but a development mule.

The firearm was designed by Edwin Pugsley, an important designer for Winchester in the first half of the 20th Century. Pugsley did not have the celebrity profile of Williams; he seems to have been quietly productive, a kind man with a mischievous personality. He rose over the years into engineering management; Winchester’s success shows he was a good selection, even if he’ll never have a biopic, a Bureau of Prisons history, or anecdotes about threatening co-workers’ lives over professional disagreements. He did have some remarkable friends, incuding Carl Swebelius of High Standard (Winchester’s toolroom wound up making several prototypes for Swebelius on the strength of this friendship) and cartoonist Charles Addams, who modeled a recurring character in his “Addams Family” strip (which ran in the New Yorker) on his friend.

Returning to the rifle itself, its appearance is more redolent of Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, than anything you’d expect to see from Winchester. The bare finish and exposed mechanicals show that it’s a long way from being ready to go to the Western Front, and it appears to have been put away when war’s end froze it in this state of arrested development. It’s clearly meant to have a bipod or tripod. What looks like it might be cooling fins actually appears to be a spring, associated with the gun mount, and acting to moderate recoil. Assuming the .50 round intended here was the .50 BMG, the weapon appears to have a 10-round magazine and be approximately the same size as a modern Barrett.

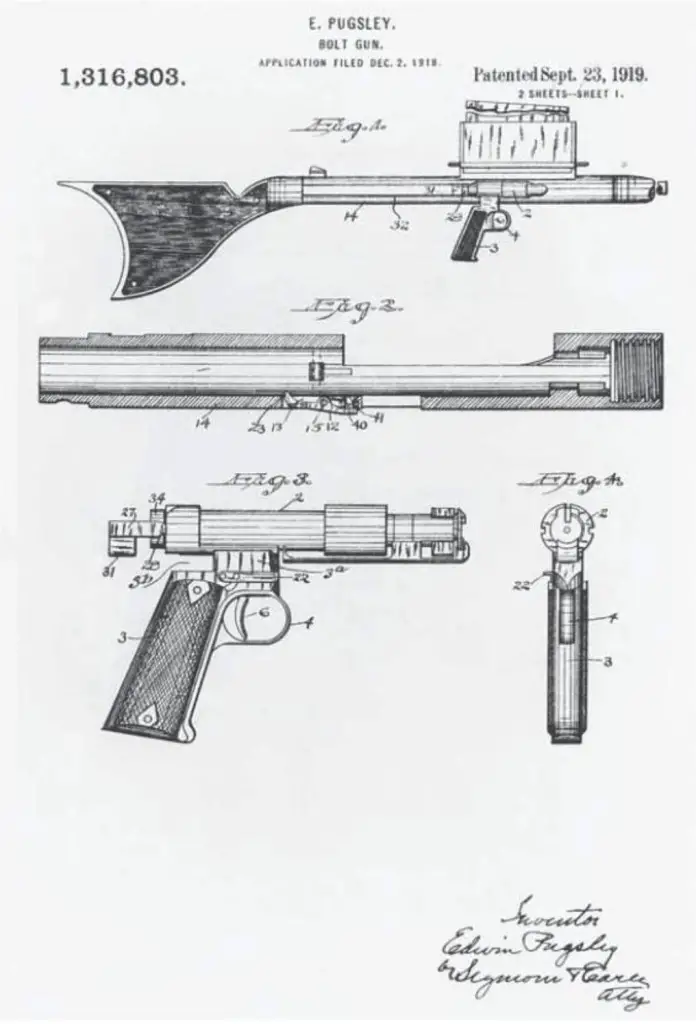

The pistol grip, which is styled like that of an M1911 service pistol, also serves as the operating handle: it has a 90º counterclockwise throw, then the gunner slides it back and the top-mounted magazine presents the next round. Here’s an image from the patent for this unusual feature.

The tubular receiver is billet steel. The strange pistol-grip/bolt has two forward locking lugs, and aft, has two widened bearing areas that slide on the inside of the tubular receiver. The extractor seems to be modeled on Mauser practice, and the ejector appears to be welded or otherwise secured inside the left side of the receiver to eject spent casings (or unfired cartridges) out the right-side ejection port.

The quantity built cannot be many, and it does not seem to have been ready for field trials at the time development was called off. Houze’s verdict was that “The anti-tank rifle, designed in 1918 by Edwin Pugsley, is of note more for its outlandish appearance than its mechanics.”1

But wait! That leaves the Williams gun still hanging out there, and we can’t have that.

The Winchester Williams .50 AT Rifle

Williams was an interesting character, an ex-con who became a firearms designer (couldn’t happen under today’s laws; ATF would yank one’s 07 FFL for hiring him) and had his own biopic (with Jimmy Stewrt, no less). The biopic is great fun but rather disconnected from real life, and definitely all wet about Williams’s design efforts — he did not design the M1 Carbine, and was not on the team that developed it. The Carbine only uses his patented gas system. What he did design, though, was a semi- and full-automatic action that scaled rather readily from .30 carbine to .30-06 to .50 BMG, and that was ultimately developed in four versions (with few cross-version interchangeable parts, but complete commonality of design and mechanical principles).

The four versions were carbine, rifle, automatic rifle (a BAR competitor that probably deserves its own post), and anti-tank rifle, the one that concerns us today. The principal virtues of the Williams design were light weight and simplicity compared to its competitors — even its carbine version was lighter and simpler than the light, simple M1 designed by another team at Winchester, using Williams’s patented gas piston. The Winchester Automatic Rifle was pounds lighter than the BAR, and the semi-auto service rifle version lighter than the Garand. A side benefit of this light weight was reduced material requirements, perhaps not a big deal when you’re making one rifle but of national significance when you’re making millions. (World War II German and Soviet weapons-selection documents also show that those nations took material use and machine time into account when downselection options for manufacture).

So of course, we had to keep looking, and in the same book we did find the 1940 Winchester Williams Anti-Tank rifle, just as Canfield told us.

Houze describes it as one of…

…a series of arms based upon David M. Williams’ design. While the carbine he had developed, as an alternative to the M1 carbine, was not completed until December1941, it was viewed as “unquestionably an advance on the one that was accepted.”

One of the advantages of the Williams’ design (Plates 294 and 295) was that it allowed the action to be stripped for cleaning or replacing broken parts simply by removing a bolt housing that was secured to the receiver by an interrupted thread locking ring. Williams also employed a superior lockwork than that used in either the M1 carbine or M1 rifle. Plate293

In acknowledgment of the design’s advantages, samples were made in .30carbine, .30-60 and .50 caliber.Though Ordnance Department tests of the .30-06 rifle version demonstrated its marked superiority over the standard M1 rifle, it was to be the light machine gun and anti-tank versions that aroused the most interest. Both of the latter incorporated an ingenious device to dampen recoil. By placing two strong coil springs on either side of the barrel breech that were attached to a recoiling lug on the barrel, Williams was able to transfer a considerable amount of the recoil forces into the springs, thereby absorbing its energy. The effect of this was to reduce the general recoil of both the light machine gun and the anti-tank rifle to the point that they were essentially recoilless. This meant that both arms could be used by infantrymen without undue stress being placed upon them during firing, a major benefit from the standpoint of accuracy as well as use. However, by the time these designs were selected for any serious testing, the war was almost over.2

One of the curiosities that surfaced during this investigation was the Winchester Tank Killer.

Curiously, it was during the testing of the .50 caliber Williams anti-tank rifle that the Winchester company seriously considered entering the automotive business for the second time in its history. On this occasion, however, unlike in 1909, the company toyed with the idea of manufacturing a light armored vehicle in which the anti-tank rifle could be mounted. Based upon a surviving photograph of the Winchester “Tank Killer,” it had an overall length of approximately twelve feet and a height of four feet. The forward section of the vehicle had sloping armor, and the tracks were powered by a 1939 Chrysler Imperial engine. No record exists as to its width or crew capacity, though the size would probably have only allowed two. Other than the one built in December 1944, it is doubtful whether any others were made.3

Unfortunately, we have been unable to find a photograph of the Winchester Tank Killer. Houze notes (p. 285) that the late Lt.Col. WilliamS.Brophy had “an 8×10-inch black-and-white print of this photograph with manuscript notations of the vehicle’s specifications,” but the current whereabouts of this image is unknown. We are also still in the dark as to how many of the AT rifles were made, and when, if ever, they were tested. It seems unlikely it would have had a chance, having less power than the .60 calibre (15.2 x 114) T1E1, although certainly being lighter and more easily handled.

Notes

- Houze, p. 189.

- Houze, pp. 276-278.

- Houze, p. 278.

Sources

Houze, Herbert. Winchester Repeating Arms Company. Iota, WI: Krause Publications, 2004.

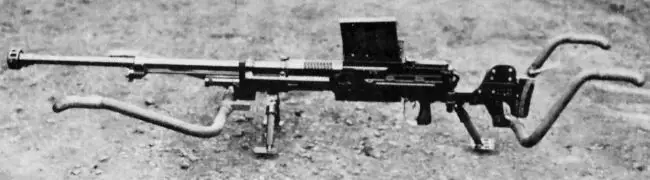

The American Cal. .60 Anti-Tank Rifle, T1 & T1E1

Germany, Poland, the UK, and the USSR all developed anti-tank rifles and used them with mixed results (the Germans, in World War I, then all of them, in the early years of World War II) Other nations including Czechoslovakia, Switzerland, Finland and Japan built anti-tank rifles, essentially huge rifles that fired a kinetic penetrator meant to kill tanks. Increasing tank armor during World War II rendered these weapons obsolete rapidly. But most people don’t know that the USA made an effort to develop its own anti-tank rifle — and a strange gun it was!

During World War II, the US Army Air Corps/Air Forces and during Korea the US Air Force, experimented with .60 caliber machine guns — the cartridge was the Cartridge, .60-caliber, T17, and it was developed in 1939 for the T1 and T1E1 Anti-Tank Rifles, a project that hasn’t seen much publicity. It made it as far as test firings in 1942 and 1944. Now all that remains is a few traces of documents that seem no longer to exist in the Springfield Armory archives, and some old photos.

The anti-tank round measured 15.2 x 114mm and was developed no later than 1939. It is a close cousin of the 20 x 102mm cartridge developed for the M39 aircraft cannon (and that would become a decade-plus later the cartridge of the General Electric M61 Vulcan powered-Gatling cannon). Some sources suggest that the 20mm came first, before the 15.2mm (.60) round, but that’s an error. Williams is correct in that the 15.2 came first, and he notes that the round, because of its MG history, is widely available to collectors:

Finally, there is one experimental ATR round which is quite commonly available – the American .60 inch (15.2 x 114). The reason for this is that although the big, gas-operated T1E1 ATR it was designed for was cancelled, the round was adopted for various aircraft MG projects during and after WW2. During this process it was necked down (to make the .50/60) but eventually reached production status when it was necked up to 20 mm to create the 20 x 102 used in the M39 and M61 Vulcan aircraft guns.1

An official history prepared by the United States Air Force described the .60, in the context of 20mm history, like this:

In 1939 the Army developed a caliber .60 antitank cartridge. Early in World War II our ordnance engineers anticipated a need for a machine gun heavier than our caliber .50 Browning and began work on this caliber .60 which would fire a 1200-grain projectile at the then “hypervelocity” of 3500 fps.

This round was later necked down to caliber .50 and achieved a velocity of 3900 fps! Later yet, it was necked up to 20 mm, known as the 60/20, and fired a 1500-grain projectile at 3300 fps. This round gradually evolved into the M50-series which is now the most widely used 20 mm ammunition in the world.2

It was a powerful round, a little harder-hitting than the excellent Soviet 14.5 x 114mm round used in the Simonov and Degtyaryev anti-tank rifles. It fired an 1180 grain (76.5 g) kinetic penetrator projectile at 3,600 feet per second (1,100 m/s) for a muzzle energy of over 34,000 ft/pounds (46 kilojoules). For comparison’s sake, 7.62 NATO produces about 2,700 ft/lb. (3.6 kJ), and 5.56 about 1300 ft/lb (1.7 kJ). As powerful as it was, if it had been fielded in 1939, it might have been powerful medicine for early-war Axis light tanks, which often had less than 30mm frontal armor.

According to a 1947 ballistics survey, the early rounds (presumably the AT gun ammo) were the Armor-Piercing TS4, BC 2, BC 3, and Tracer BC 3 rounds, and possibly the incendiary T1E6 and HE T19. The rounds that were probably postwar MG rounds (used in guns based on wartime Mauser revolver-cannon designs) included Ball, Incendiary, API and API-T all with T designations.3

But the rifle, which might have been adopted if it were ready with the ammunition in 1939, was not ready for testing until 30 October 1942. By this time its penetration, 32mm at 450m, had been left behind by combat-driven armor development; desultory tests continued, with the weapon being fired once again in June 1944. The gun was ultimately put away without ever being publicized — which is why so many people don’t know the USA had an AT rifle.

The T1 (later T1E1, after an unknown modification) Anti-Tank rifle was a man-portable, gas-operated, tripod-mounted semi-automatic anti-tank rifle designed to be emplaced, displaced and served by a crew of two to three men. The tripod appears to be that used on the M2HB .50 caliber machine gun, and the T1E1 appears to have been about as much a challenge to move and emplace as a .50 can be.

Its design history is lost in time — the only archival material a computer search of Springfield Armory reveals is a single 3/4 view photo — which itself has not been digitized. Apart from some references to the ammunition for its importance in the early development the hugely successful NATO aerial rounds, DTIC is silent on it, and even the familiar backdoor into DTIC through an NTIS search produces only ammunition reports.

The most unusual feature of the T1/T1E1, compared to foreign AT rifles (especially repeating and semi-auto guns), was its feed: the stout .60 rounds were loaded in a Hotchkiss-style tray, which almost certainly makes the T1E1 the last firearm ever designed with this feed. (Japan used several improved Hotchkiss designs to great effect in WWII, but the Japanese weapons were designed earlier). Trays were made to hold five and eight of the .60-cal. rounds. The strange buttstock of the T1E1 was also reminiscent of some early Hotchkiss versions.

The weapon had, in its testing phase, no iron sights and what appears to be a standard rifle telescope.

What became of the test article or articles that was fired in 1942 and 1944 is not known. Scrapping seems highly possible. Had no shaped-charge weapons been available, it might have gone to combat. But the shaped charge was a short-cut to much more terminal effect on enemy tanks than the anti-tank rifle could hope for.

The two photographs shown here, which were scanned from Hoffschmidt but are clearly official US photos, are the only two we have seen of the T1E1. (The Springfield catalog tantalizingly holds out the possibility of a third). It is possible that more documentation exists, uncatalogued, in some museum or other. To our great frustration, what you read in this blog post is just about it.

The T1E1 is remembered now as a dead-end, but an exceedingly powerful one. Other anti-tank rifles tried to get greater velocity with smaller calibers, like the German and Polish 7.92mm guns, or greater power with larger explosive shells, like the many 20mm and a monster Swiss 24mm gun. But in the end, improvements in tank armor on the one hand, and Monroe Effect-based shaped charge weapons on the other, rendered them all obsolete. All of them, and most especially the T1 of which no example is thought to survive,

Notes

- Williams.

- Davis, pp. 4-5.

- Hitchcock, table on p. 29.

Sources:

Davis, Dale M. Historical Development Summary of Automatic Cannon Caliber Ammunition: 20-30 Millimeter. Eglin AFB, FL: Air Force Armament Laboratory, 1984 Retrieved from: Fulltext PDF at: http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a140367.pdf

Hitchcock, H.P. Ammunition Data for Spinning Projectiles. Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland: Ballistic Research Laboratory, 1947. May be available at: http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a800469.pdf (or can be accessed through NTIS/NTRL search).

Hoffschmidt, E.J. Know Your Antitank Rifles. Stamford, CT: Blacksmith Corp., 1977.

Rottman, Gordon L. The Book of Gun Trivia: Essential Firepower Facts. New York, 2013: Osprey Publishing.

Williams, Anthony. An Introduction To Anti-Tank Rifle Cartridges. The Cartridge Researcher: The Bulletin of the European Cartridge Research Association, Nov-Dec 2004. Updated version retrieved from: http://www.quarryhs.co.uk/ATRart.htm

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.