This memorable photo, by an unfortunately uncredited National Guard photographer, shows something that just plain wouldn’t have happened prior to the Global War On Tourism and its various offspring, like the unpleasantness in Iraq. It also happens to be a great photo. So after you look it over, we’ll give you the official credit line and link, tell you why it took the war to make this photo happen, and talk a little bit about the once-revolutionary 40mm high-low pressure grenade and the systems that fire it.

Our caption would be: “Tooonk!”. The Army’s somewhat more prosaic one is:

Staff Sgt. Nehemiah E. Taylor, with the 298th Support Battalion, Mississippi National Guard, fires an M203 grenade launcher during the individual weapons qualification weekend at Camp McCain, Miss.

Nice shot. The muzzle gases are captured, and the round is almost frozen in time: enough so that you can see it’s a blue-plastic-capped M781 training-practice round. (The filling of this round is a Hunter Orange chalk powder, so that soldiers can mark the fall of the shot readily. M203 and other 40mm gunners improve rapidly when given the chance to live fire these rounds).

Before the war, Army practice would never have been to let a service support soldier like this live fire his M203. Soldiers didn’t even see the weapon in basic combat training, unless they were on their way to combat arms assignments. Even combat arms soldiers seldom live-fired 40 mm. Only SOF tended to get enough ammunition for a reasonable training schedule, and even those didn’t always get all the ammo they really needed. During periods of constrained budgets, it was common for entire units to just get enough of an ammunition allocation to allow each individual to fire his rifle for qualification — no additional ammo for practice.

In SF, we routinely bought our own ammunition during these periods, which was a major violation of Army regulations. The Army is very jealous about its weapons. You are not permitted to load them with your own ammunition, take them to your home, or even take them to the range in a privately owned vehicle. Of course like any other Army regulation, there is a legal way to get around or waive these regulations, but it requires the conscious and strenuous efforts of your staff judge advocate, who may or may not be interested in doing that sort of thing.

As we learned, you can even buy 40 mm training practice ammunition, but it’s rather expensive. The 40 mm warshots – HE or HEDP rounds for example – were a different matter. Each round is considered a destructive device.

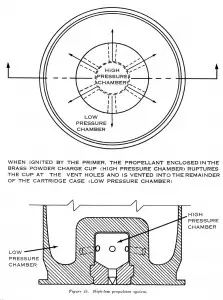

The high-low ports come in several varieties, as seen here. All function similarly.

The 40 mm design is ingenious. It’s initiated by an ordinary percussion primer, like a rifle round. Inside the casing the powder charge pressurizes a smaller, internal high-pressure chamber, with small ports to the larger casing. The ports let the high (up to 25,000 psi) pressure bleed comparatively slowly into the larger part of the casing; the low pressure area peaks at around 3,000 psi at midcase and only 1,400 or so at case mouth (See Slide 19 here). This is called the high-low pressure system and the tight containment of the high pressure lets the casing and barrel be made of lightweight materials — these days, the cases are aluminum or plastic, and the barrels generally machined aluminum forgings.

The initial 40mm was the break-action M79, a kissing cousin of everybody’s first H&R single-shot shotgun. The 79 had a stout stock with a thick rubber recoil pad, necessary because, while the 40 mike-mike has a soft report (Toonk!) it has a pretty beastly recoil.

The Army considered arming a soldier with an M79 suboptimal. The M79 was his primary weapon, but for close-range self-defense he was issued only an M1911 .45. So from the very beginning, they were interested in a hybrid weapon that was both a rifle and a grenade launcher. For years, this led the Army down the blind alley of the SPIW, which certainly deserves a post or post of its own. The SPIW was meant to combine a flechette firing-rifle with a multishot semiautomatic grenade launcher. It required, in engineering terms, the scheduling of too many inventions and never succeeded.

The Army’s fallback was to suggest an under-barrel weapon that would attach to the then-new M16A1 rifle. Several vendors worked on this project and Colt initially provided test versions that were used in the field as the XM148. Colt developed an improved version that responded to Army criticism of the XM148, but the improved Colt system, the CGL-5, was beaten out by a system designed by Aircraft Armaments Inc., which was type standardized as the M203. The last laugh, though, was on AAI: Colt received the contract to actually produce the AAI system.

The M203 is slowly being replaced by the improved M320 grenade launcher. As this photo shows, 203s are still in very wide use.

One last thought — Army photographers hang it out with the combat units for a SP4 or sergeant’s pay, and bring back some images that become iconic (and get ripped off and stamped with copyright attributions by Corbis or AP, but that’s another story). We’re sure this guy or gal would rather have spent that day on the range with the Mississippi Army National Guard than downrange in Anbar Province, but we think the photog deserves credit. Can anybody find out who it is? We’ll update the post.

UPDATE! 1500R 20140117

Thanks to commenter Wes, who did what we probably should have done and picked up the phone to call Camp Shelby, the photographer has been fingered. He wasn’t a PAO at all, but MAJ Andy Thaggard, the Mississippi National Guard’s Command Historian. Thanks again to Wes, to MAJ Thaggard for the fine shot, and to SSG Taylor for letting him take the picture whilst firing. “It was a good day at the range,” says the Major. Is there any other kind? -Ed.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

29 thoughts on “It took a war to make this training photo happen”

FWIW: Contrary to “The Black Rifle” and what I originally posted in my timeline, AAI did receive the first production contract for 10,000 M203 after it was officially standardized August 29, 1969.

I first learned of AAI’s contract for 10,000 M203 through a collector who had AAI-marked M203 receiver stubs with serial numbers in the four digit range. Years later, I discovered in the December 1969 edition of “American Rifleman” that AAI was awarded a $2,953,000 contract for 10,000 M203. A search in the National Archives for AAI’s Fiscal Year 1970 (July 1969-June 1970) contracts in Federal Supply Class 1010 (Guns over 30mm up to 75mm) revealed that a contract was awarded in September 1969 for a value of $2,954,000. The value discrepancy could simply be a difference in rounding. The contract’s estimated date of completion was December 1970; however, funding actions were still awarded until June 1973.

I believe the first AAI production contract was DAAG25-70-C-0127. Colt won the open competition in 1971 for contract DAAF03-71-C-0300.

Interesting posts. I was reading the bio of the founder of AAI in, IIRC, SADJ? Something in dead tree, not online, recently, and the same story of the contract going to Colt, not AAI, was recounted.

Every 203 I personally handled was made by Colt, FWIW, but that could just be coincidence. I know guys who never saw a Hydramatic or H&R M16A1.

Everyone is parroting “The Black Rifle.” Ezell knew better when he edited the 11th edition of “Small Arms of the World.” (See page 618.) So I’m going to blame Blake Stevens for the gaff. As you might imagine, I have a list of errors that I’ve found in that book and other Collector Grade titles.

It drives me bat**** that Blake did not footnote those books. So much information, so much duplicative effort to find out where it came from. Once it’s in print (or on the net), it never dies.

If you want endnotes, you’ll love Bruce Canfield’s new M1 Garand book. There’s well over 2,000 citations. Alas, I’ve already found errors caused by reciting other authors’ misguided identifications.

One is courtesy of Blake Stevens again, this time from pages 25 and 26 of “US Rifle M14,” where Harry H. Sefried’s prototype of a mag-fed, selective fire M1 was misidentified as Garand’s original prototype of that configuration. Ironically, Canfield had only just pages earlier identified the same rifle as Sefried’s design, complete with pictures from his US patents!

Another has been repeated before by Scott Duff and Robert Bruce in which a 1962-vintage photo of Garand holding an early Springfield SPIW concept model is misidentified as Garand demonstrating his ill-fated T31 prototype.

Hadn’t Garand also retired by 1962? Rayles says that Garand lost interest in consulting with SA when he found that the government docked his pension for every day he consulted! They found a work-around by having him consult for a machine shop to which SA contracted out a lot of prototype work.

Here are some of the other errors I’ve noted in “The Black Rifle.”

Page 109: The creation of Ordnance Weapons Command (OWC) occurred in 1955, long before McNamara’s reorganization of the Army in 1962. However, the OWC was absorbed by the Army Materiel Command, becoming the Army Weapons Command (AWC, or later WECOM).

Page 149: The book incorrectly identifies Maj. Gen. Elmer J. Gibson as an USAF officer when discussing Colt’s presentation of the first M16 built under the Army’s contract. Actually, Gibson was the AMC’s Director of Procurement and Production. Prior to that, he had been Commanding General of the Ordnance Weapons Command and “Project Manager – M14 Rifle”.

Page 153: The authors assume that the Olin M193 that failed the USAF’s plate penetration tests in 1964 was loaded with WC846. However, this event pre-dated the final approval of WC846 by the TCC. Judging from the PMR’s Weekly Significant Action Reports (WSAR), the Olin lot in question was likely from the initial 500,000rd batch loaded with IMR 4475.

Page 164: The book displays a handwritten note from Major General Nelson Lynde which passed along with instructions from Gen. Schomburg to Ordnance Tank-Automotive Command (OTAC) not to include the “Fairchild rifle” in public demonstrations or displays. The authors interpreted this as referring to the AR-16. However, take note of the personalized note pad; it is from when Lynde was Commanding General of OTAC.

According to his bio posted in the Ichord Hearings transcripts, Lynde left that position in 1959 to become Assistant Chief of Ordnance for Field Service. He stayed there until 1962 when he became Commanding General of Ordnance Weapons Command. So either this note predated the public introduction of the AR-16, or for whatever reason, Lynde was still using up his old note pads. On a side note, Maj. Gen. August Schomburg was Assistant Chief of Ordnance for Research and Development from April 1956 to May 1958. At that point, Schomburg became Deputy Chief of Ordnance, where he served until February 1960.

Page 222: The authors assume that Colt’s evaluation of the 1/14″ and 1/12″ barrels were delayed by the 1967 strike. However, Colt’s Paul Benke quoted accuracy results from their testing in his July testimony before the Ichord Subcommittee.

Page 252: The book states that Maj. Gen. Lynde gave an order to Col. Yount in November 1966 regarding M16 optics and mounts. However, Lynde had retired from the Army in March 1964 and months later went to work for Colt Industries (previously Fairbanks Whitney). If you’ll remember, the Ichord Subcommittee seized upon this as a possible example of corruption in the procurement of the M16. Perhaps they meant whoever was the current WECOM commander?

Pages 256: The book shows Col. Isaacs becoming PMR in September 1967. Actually, Isaacs had been chosen as PMR by at least July. According to Yount’s testimony before the Ichord Subcommittee, Isaacs was attending school at the time of the hearings. Perhaps September is when Isaacs first signed off on the PMR WSAR? While Lt. Col. Engle only served as acting PMR prior to Isaacs taking office, the book makes a couple of other references to Engle being PMR during 1968. However, the PMR WSAR doesn’t mention Engle during these occasions. For what its worth, Isaacs left as PMR to become the Commanding General of Tank-Automotive Command. As a result, he received a promotion to Brigadier General. The last PMR, Col. Wing, went on to become commanding officer of Frankford Arsenal’s laboratories sometime around 1973.

Page 324: The book lists 1967 as the start of Philippine M16 production. However, according to the GAO, State Department telegrams, and the CINCPAC Annual Command Histories, it was 1974 when the Philippine government signed the memorandum of understanding with the US for setting up domestic M16 production. In addition, the DoS and CINCPAC documents indicate that the Philippines did not have anything close to 50,000 Model 613 on hand in 1967. Given the fit that Congress threw over Colt selling 20,000+ M16 to Singapore, one can hardly imagine that such a huge sale to the Philippines would have gone unmentioned.

On the Phillipine M16s, ISTR that some were furnished for Filipino non-combat units (engineers?) that served in RVN. Most images I’ve seen of Filipinos from the 1960s show them with US WWII/Korea vintage weapons, lots of M1/2 carbines.

Your copy of TBR must be pretty heavily marked up.

Oh yes, Garand was fully retired long before 1962. Springfield kept bringing him back for various “dog & pony shows” so his credibility would hopefully rub off on their latest R&D and production projects.

This is the photo in question:

http://ww2.rediscov.com/springar/VFPCGI.exe?IDCFile=/springar/details.IDC,SPECIFIC=4021,DATABASE=BIBLIO,

Otto von Lossnitzer was at the time head of Springfield’s Project Control Office. Previously Mauser’s former head of R&D, Lossnitzer came to Springfield as part of Operation Paperclip. Herman Hawthorne was then head of the Armory’s Development Division.

In July 1966, MACV approved delivery of 630 XM16E1 rifles to the Philippine Civic Action Group. However, I’m not certain if SecDef McNamara or CINPAC Adm. Sharp squashed it in late ’66 or early ’67. They didn’t want M16 rifles going to our Asian allies ahead of deliveries to US units. The commander of the ROK detachment, Lt. General Chae Myung-shin was seriously pissed off and complained to the press after news of the Singapore sale became public.

(Note: LTG Chae’s name was mangled in the Ichord Hearing transcripts as Chu Chinn, and this error has continued to propagate.)

The following ARFCOM thread has photos of the AAI production M203 receivers:

http://www.ar15.com/mobile/topic.html?b=6&f=21&t=405014&page=4

I can’t find my link to the other Photobucket user who had photos of AAI receiver stubs, along with pictures of the other GLAD candidates. I want to say the latter were taken at the Oregon Military Museum.

Interesting thread. Kid and I were going to hit Springfield Armory today or tomorrow, but today we got snow-ked and tomorrow I have the sitter duty with my brother’s family. So that may slide to next or some future weekend.

“Before the war, Army practice would never have been to let a service support soldier like this live fire his M203. Soldiers didn’t even see the weapon in basic combat training, unless they were on their way to combat arms assignments. Even combat arms soldiers seldom live-fired 40 mm.”

Errrr… Not so much. Check the STRAC standards-All assigned M203 gunners were required to do a qualification on the weapon at least annually, out in the “Big Army”, and that applied to the support people as much as it did us combat arms, types. We also usually got a ration of live HEDP to fire, as well, typically one or two rounds per gunner.

I’m not going to say that the qual course is enough to attain or retain proficiency with the weapon, but there was a lot more opportunity to at least familiarize oneself with the weapon out in the Big Army than you’re implying. Even in the CSS units-We used to run ranges all the time for the Combat Heavy units we had, along with the NBC and others that were assigned to our brigade.

well, the big army might have gotten 203 ammo on a regular basis, but the units i was in with the CA ARNG rarely, if ever, got any, and that includes Mech Infantry & Armored Cav, as well as CS & CSS units.

as for the photog, i’ve shared this article with a friend who’s PAO with the TX ARNG, to see if she has a way to ID the artist.

In the seventies and eighties those requirements might have existed on paper, but the qualifications would have happened the same way — on paper. In my basic we got to fire one nine-round belt from an M60, and other than that, we just qualified on the M16A1.

I was there, during the 1980s. The qualifications happened, and the ammo was there, even for schoolhouse support units like the first one I was assigned to. I was the armorer back then, and I had to go out to every flippin’ range we ran. It was the same story, in Germany, when assigned to a Corps-level support unit.

The 1970s I can’t speak to, but from 1983 on, I can’t recall a time when we didn’t have enough ammo to meet STRAC standards.

Now, in the 1990s, they did get seriously stupid with the training ammo where I was. M16 qualifications were so strictly rationed that if someone screwed up on the qual range, that was their only chance. We’d have guys who needed to improve their qual scores for a promotion board who would have to take a weapon and a vehicle over to the qualification ranges, and start begging other units for a chance to re-shoot. When we ran the ROTC ranges, it was a godsend, because that would mean we’d have all the ammo we needed to get guys the promotion points they needed if they’d had a bad day on the range when we’d had our one shot at it for that year. A lot of us senior NCOs wound up giving our rounds over for some junior guy to get a chance to improve his score.

Even so, the ammo was always there for at least the minimum STRAC requirements to be met, even if it was for just the one iteration per troop.

The perception from within the SF community may have been somewhat skewed, because there were a lot of complaints about “lack of training ammo”, but the reality was that the ammo was out there, it was just that the units that were utterly inept at parceling it out. I recall one occasion where I was out doing a range recon for an upcoming MK-19 shoot, and I found the range occupied by a small team of around five guys, who were shooting case after case of M203 rounds. They had the open cases out by the firing points, and were just throwing the training rounds downrange, without really paying attention to anything like scoring or the like. Gave a huge “WTF?” to the NCOIC of the range, and got a huge sigh, and: “It’s the end of the fiscal year, the battalion hasn’t scheduled an M203 range, and we’re out here burning up the allocation…”.

Typical idiocy, out in many of the support units. It wasn’t the lack of ammo, it was usually the lack of sense. Had you asked the random troop out in one of those units whether or not he’d qualified on something like the M203, he or she would have likely told you “We don’t have the ammo…”. Reality was, they did. Their leaders just didn’t know how to use it, or how to prioritize it.

In Germany in the early ’80, with a physical Security MP Company (280 personnel) guarding classified munitions, we had ordered sufficient .45 ACP ammo for training and qualifying the guards. When we went to pick up the ammo, the ASP gave us 1 each box of 50 rounds in instead of the thousands we ordered to qualify with. I asked the WO there “how in the hell I was suppose to qualify 4 platoon of MPs with 50 rds.?” I had shown him the request (DA 581) for the ammo from a year earlier with all the updates, (not one said that we did not have the ammo) he just shrugged his shoulders said “we don’t have it”. After returning to the Company and several calls from our MATO and S-3 shop to the higher ups and way higher ups, a week later we were told to go and pick up our ammo. Of course we had cancelled our range day and had to reschedule it. We later heard through the grapevine (true or not) that our ammo went to the Marksmanship unit so they could train for a up coming competition . So much for priorities.

I remember in 1966 at Ft. Leonard Wood. MO. (Combat Engineer Training AIT) We went to the range and were introduced to the M-79. I remember seeing the recoil pad and telling my buddy to pull it in tight to his shoulder ’cause I was sure it was going to kick like a mule. The army had never been too big on comfort (Ergonomics). Surprisingly. the “2 gauge” as we called it was manageable and quite accurate to the standard ranges we used. There was a lot of ammo floating around during the height of Viet Nam so we got a chance to fire smoke, WP, and HE.

I enjoyed the explication of the hi-low design.

I have to disagree with the statement that the M79 had beastly recoil. I used one on various occasions from a UH1H, including an afternoon request/assignment to attempt to shoot both HE and CS into the caves on the north side of the Marbles, which was my biggest-ever lifetime test of reverse lead and bullet drop estimation. It involved typically two rounds fired per pass and passes over about two hours. I was always struck by how mild M79 recoil was, compared with a 12-gauge 870. The only exception was the beehive round (I only ever fired one), and even that was’t bad. The HE were not bad. Gas rounds were almost zero recoil.

RE photog credits, shot an email to the PAO at JFTC Shelby; we’ll see if she can ferret it out.

You’re right; it’s a damned fine shot.

FWIW, OCS Basic @ Ft. Knox, circa 1983, had us not-even-soldiers-yet candidiots pumping out half a dozen or so M-203 practice rounds. The high point of my day, having paid attention to the COI on use of the installed tangent sight, was getting to the second station, which my Drill Sgt/SFC was monitoring, and thumping the round right through the target window at >100 yds. At which point he smiled, and said “John fucking Wayne. Good shot. Move out!” (IIRC, aced the entire course, beginner’s luck + it’s not a difficult weapon system to master.)

It’s possible that they had decided we were a higher training priority than actual troops, but I leave it to the host to decide if such was likely or not.

With Big Green, never ascribe to malice what can be explained by bureaucracy and mismanagement. That was actually after the Reagan era ammo started flowing. What killed us in SF was that our allocations were tied to the Ragnars, who brought every round they could beg, borrow or steal to Grenada, expecting more Cubans to be inclined to marytrdom por socialismo than was actually the case. Among other things, they brought every M67 90mm round in the world inventory to the island. Then, once the pallets had been broken down, the USAF would not let them be repalletized for “safety.” (These guys sit at the pointy end of a tinfoil machine full of highly inflammable jet fuel, and they’re worried about unarmed/unfuzed ammunition. Oh brother).

I believe it was at the time the largest EOD blast in history. It would have set off every car alarm on the island, if the alarms hadn’t all been disabled when the cars were stolen on the mainland (long story).

Follow-up on photo provenance. PAO at Shelby ferreted out that MAJ Andy Thaggard, who is by sig block Cmd Historian for MS National Guard, deserves our thanks for the photo. He’s also apparently damned good with a camera. In his words, “Glad you like the pic, it was a good day on the range.” A good day at the range indeed. Nice job Major.

Thanks Wes! We’ll edit to make sure MAJ Thaggard gets credit.

Reloadable training rounds, now that would be an idea….

What’s the mechanical accuracy of these grenade launchers? And what kind of overall accuracy can a skilled shooter expect versus a semi-trained shooter? Are “groups” on the order of 10 yards at 100 yards?

And what’s the lethal radius versus the injury radius of the standard grenade in typical terrain?

Those are good questions. Because of the high trajectory, you’re limited to 100-200m against a point target. (Like shooting through a window, one of the ranges we used to use had a window at 175m and I could put a round through that pretty consistently). Anybody who’d fired a few rounds and used the sight properly could hit a window at 100m. Area target like troops in the open you could hit with plunging fire to about 300-350m. At that point you’re at high angle (in the artillery definition) and going any higher brings the round back towards you.

The old M79 had a ladder sight and a close in battlesight (60m) when you flip the sight down, but it was calibrated for 1960s ammunition. If you used that battlesight with 1980s or newer rounds, the round’s impact was more like 30 than 60m and you could (and I did) hit yourself with shrapnel from the round. At that range it was not very lethal — it only penetrated about 1/32″ — but it was still hot enough to burn your skin.

The Army claims the following for all 40x46mm antipersonnel grenades: kill radius of 5m, and casualty radius of 130m (the latter is greatly exaggerated, in my opinion). During the Vietnam War they claimed a kill radius of 5m and an “incapacitation radius” of 15m for these same rounds like the M381. The M381 went out of service because it was hazardous to fire in forests due to its very short arming distance (as little as 3m). Real problem in Vietnam triple-cap.

Thanks, Hognose.

So, if a soldier can put a grenade within a meter or two of his target, it sounds like a smaller grenade might be in order.