One thing about the people of the gun: we’re conservative. By that, we don’t necessarily mean that we want 15 carrier groups back, eager to cut taxes and services, or sorry that mandatory chapel was gone by the time we went to college. There are actually card-carrying ACLU members and ivory tower socialists among us, but they’re conservative about their guns. For every reader who’s up to date on polymer wonder pistols, there’s about three who wish you could get a new Python. (The reason they can’t is that they don’t want it $3,500-4,000 bad, which is what an old-style hand-made perfect Python would cost to make today). Or a new Luger. For every one of you guys following the latest in M4 attachments (hey, let’s play “combat Legos!”), there’s a few who’d buy a new MP.44, if they could.

Every once in a while, gun manufacturers decide to satisfy these consumer yearnings with product. Sometimes, they succeed. Sometimes, the 10,000 guys who told them they were down for a semi-auto Chauchat turn into 10 guys who buy one and the businessmen get to undergo the intensive learning lab called Chapter 7 bankruptcy. The question becomes, if you are raising a zombie firearm from the dead: how? Even the original manufacturers tend not to have prints and process sheets for >50 year old products, and if they do, the documents are ill-adapted to the way we do things now. If your original product was made in Hiroshima or Dresden pre-1945, or Atlanta pre-1865, odds are the paperwork burned. If the company went tango uniform even ten years ago, rotsa ruck tracking down the design documents.

So, you’re sitting here with a firearm you know you could sell. You have the rights to reproduce it, because any patents and copyrights and trademarks are either in your possession or expired or defunct. Your problem is reverse engineering. It turns out that this is a very common problem in the firearms industry, and the path is well beaten before you.

Some Examples of Reverse-Engineered Drawings

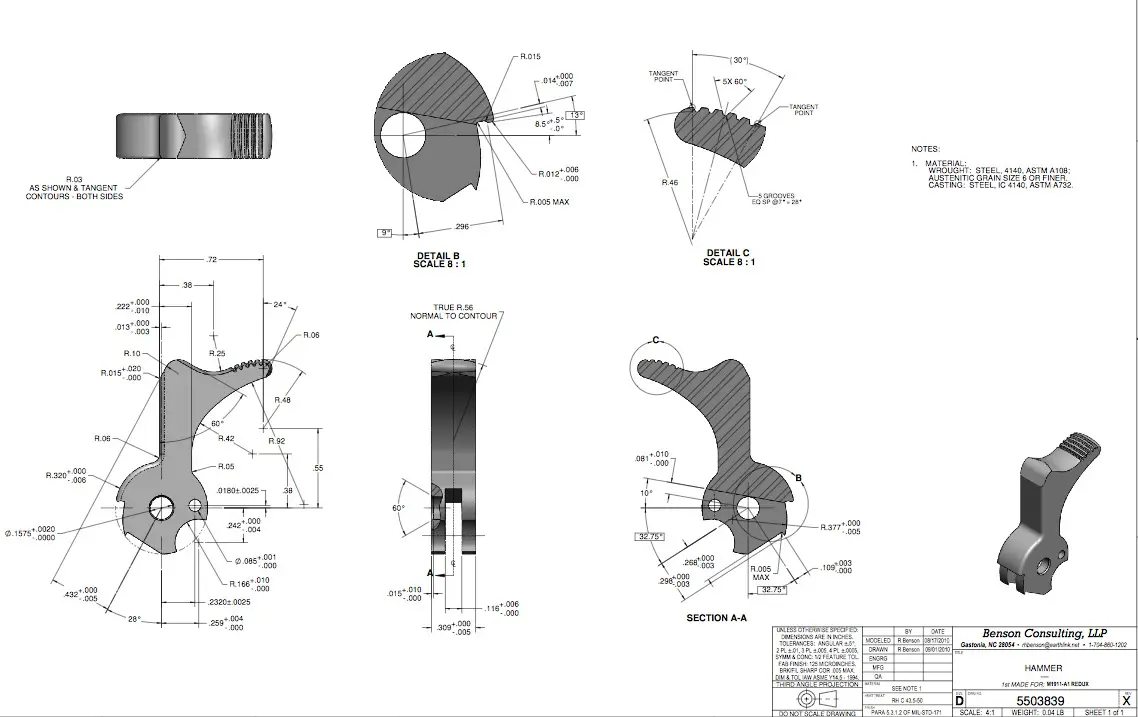

People can do this with some calipers, a dial indicator, and some patience. Rio Benson has done that for the M1911A1.

He explains why he thought a new set of documents were necessary in a preface to his document package:

Historically, when the drawings for John M. Browning’s Colt M1911 were first created, there was little in the way of ‘consensus’ standards to guide the designers and manufacturers of the day in either drawing format or in DOD documentation of materials and finishes. For the most part, these were added, hit or miss, in later drawing revisions. Furthermore, due to the original design’s flawless practicality and it’s amazing longevity, the government’s involvement, and the fact that in the ensuing 100-plus years of production the M1911 design has been officially fabricated by several different manufacturers, the drawings have gone through many, many revisions and redraws in order to accommodate all these various interests. These ‘mandated by committee’ redraws and revisions were not always made by the most competent of designers, and strict document control was virtually non-existent at the time. All of this has led to an exceedingly sad state of credibility, legibility, and even the availability of legitimate M1911 drawings today.

He modeled the firearm using SolidWorks 2009, with reference to DOD drawings available on the net, and his own decades of design and drafting-for-manufacture experience. The results are available here in a remarkable spirit of generosity; and if you want his solid models or his help producing this (or, perhaps, on another firearm), he’s available to help, for a fee.

In a similar spirit, experienced industry engineer David S. Findlay whom we’ve mentioned from time to time, has published two books that amount to the set of documents reverse-engineered from an M1A1 Thompson SMG and from a Sten Mk II. The limitations of these include that they come from reverse-engineering single examples of the firearm in question, and the tolerances are based, naturally, on Findlay’s experience and knowledge. So his reverse-engineering job may not gibe with the original drawings, but you could build a firearm from his drawings and we reckon the parts would interchange with the original, if his example was well representative of the class.

In a similar spirit, experienced industry engineer David S. Findlay whom we’ve mentioned from time to time, has published two books that amount to the set of documents reverse-engineered from an M1A1 Thompson SMG and from a Sten Mk II. The limitations of these include that they come from reverse-engineering single examples of the firearm in question, and the tolerances are based, naturally, on Findlay’s experience and knowledge. So his reverse-engineering job may not gibe with the original drawings, but you could build a firearm from his drawings and we reckon the parts would interchange with the original, if his example was well representative of the class.

On the other hand, Eric A. Nicolaus has published several books of cleaned-up original drawings of the M1 Garand, the M1D, the M1 and M1A1 carbines, various telescopes, etc.

On the other hand, Eric A. Nicolaus has published several books of cleaned-up original drawings of the M1 Garand, the M1D, the M1 and M1A1 carbines, various telescopes, etc.

Nicolaus’s books provide prints like the Findlay books do, but they’re not reverse engineering. They’re reprints of the initial engineering, cleaned up and republished. Not that there’s anything wrong with that.

Sometimes the Industry needs Reverse Engineering

A perfect example is when planning to reintroduce an obsolete product. Most manufacturers that have been around since the 19th Century never foresaw the rise of cowboy action shooting, but now that it’s here, they want to put their iconic 1880s products in the hands of eager buyers. Or perhaps, they need to move a foreign product to the US (or vice versa). In this case, reverse engineering the product may be less fraught with risk than converting paper drawings which use obsolete drawing standards, measures and tolerancing assumptions. You may recognize this reverse-engineered frame:

If you are exploring a reverse engineering job, there are several ways to do it. The first is in-house with your own engineers. (You may need to ride herd on them to keep their natural engineers’ tendency to improve every design endlessly in check). The next, is to outsource to an engineering consultancy that does this. The third is to use a metrology and engineering company, like Q Plus Labs, from whom we draw that pistol-frame example. They say:

[W]e offer numerous reverse engineering methods and services to define parts or product. Q-PLUS provides everything from raw measurement data to parametric engineering drawings that correspond to a 3D CAD solid model! We also offer reverse engineering design consulting to point you in the right direction.

- Digitizing & Scanning

- Measurement Services

- 3D CAD Solid Modeling

- Engineering Drawings

In other words, you can go there to have them do, essentially, what Rio Benson did with the 1911 with your product. They can digitize an item from 3D scanning, or they can take a drawing and dimension it from known-good examples. Given enough good examples, they can actually determine tolerances statistically and substantiate them to a level that will satisfy regulatory agencies such as the FAA. (This lack of a range of parts and statistical basis for the tolerances is, in our opinion, a rare weakness in Findlay’s single-example approach).

Reverse engineering has gone from something in the back alleys of engineering or attributed to overseas copycats, to something firmly in the mainstream of modern production engineering.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

24 thoughts on “Firearms Reverse Engineering”

Speak for yourself about those 15 carrier groups!

Good post!

That is pretty interesting right there. I can imagine the hard work involved in reverse engineering a fire arm. Quite a feat. Must be a lot of unknowns.

From actual experience I can say ridged tube assemblies for aerospace under AMS processes and procedures and quality procedures for FFA qualified tube assemblies, a master tube and or tube assembly, along with the original fixturing, produced by the original designing company, and sometimes subsequent sub contractors, is usually retained in permanency.

They are an incredibly valuable, never mind handy hands on visual and checking reference resource in first run and production processes. It is not unusual for engineering, quality, inspection, and every process involved to rely on these masters even with excellent blue prints and specification reference books at hand. Nothing like holding that original in your paws. They are priceless items when building tooling and jigs. FFA sanctioned O&R depots are another form of reverse engineering. The specs require you have some section of the original part incorporated in the finished rebuilt or overhauled piece. Not infrequently you have no B/P’s or any other reference but a worn out, damaged, or destroyed original. Long as you retain something original you attach the repair to your good. If you can save the section which has the part or serial number even better.

looks like a latter day PPK receiver?

PP or PPK/S. A true PPK is set up for wrap-around grips. The PPK/S was created because the PPK didn’t make enough points on Tom Dodd’s Nazi-derived “sporting purposes” checklist.

Oh ya, Dodd. Like the clap, a gift that keeps on giving.

Findlay’s TSMG looks like a first rate work.

1) If you want but can’t afford a classic Python consider a Korth.

2) I would save my lunch money from now until the Second Coming to acquire a Baby Nambu in a modern caliber, especially .32NAA. Wouldn’t that be a sweetie?

Noticed this:

http://www.amazon.com/Full-Circle-Treatise-Roller-Locking/dp/0889354006/ref=wl_mb_wl_huc_mrai_3_dp

Quoth Amazon, “You purchased this item on November 5, 2013.” It’s a very comprehensive book but contains no information whatsoever on the CZ 52. Or on the HK P9 either!

One thing it does have is some description and images of an early solid-model of the MP45 developed by German immigrant (via Canada) Ralf Dieckmann of Prescott, AZ.

Well, of course not. I’ll bet it doesn’t go very far into MG42 or StG57 territory, either. For some folks, only the CETME-derived HK products really count as being true roller-delayed weapons.

All the same, I really need to buy that book, when I’ve got some spare fundage.

There’s a lot on the early patents and the MG42, and then the Mauser-werke experiments that led to the abortive StG.45 and the CETME. Lots and lots and lots of CETME variants.

Could it be the same Ralf Dieckmann that produced this?

https://www.gunandgame.com/threads/ralf-dieckmanns-bridgeport-arms-company-p-66.134089/

It looks like he had a hand in the design of the Ruger Gold Label shotgun, and he also designed a semi-auto .50 BMG rifle for McBros.

http://www.battermans.com/firearms-gallery/dieckmann-50-caliber-semi-automatic-rifle.html

I believe that is the same man, yes.

I’m still waiting for pedersoli or similar to discover the Norwegian kammerlader rifle. A 1830s designed and 1840s introduced breech loaded percussion rifle must be interesting to enough people to warrant production.

Oh, those Italians who reproduce cowboy era guns are true experts in reverse engineering. But they often improve the firearms they reproduce far beyond their original quality. They almost can’t help doing that, because today’s metallurgy is so far superior to that of the 1800s.

I’ve often wondered why Italy takes the lead in doing this. All I can figure is it has something to do with spaghetti westerns and Ennio Morricone scores.

Worked in Northern Italy for five years. Northern Italian engineers are – bar none – the best short production run manufacturing engineers in the world. They cleverly and creatively use the tools at hand to make a broad variety of parts cost effectively in small volumes. CNC machining has reduced their advantage in some parts, but their short run stamping and woodworking technology is still unrivaled.

And yes, Italian manufacturing engineers all love Western movies. My SAA revolvers and Winchester leverguns always got a well videoed workout when they visited me in the USA. Few originals over there.

I have some of the the books mentioned. The Findlay Thompson book is good. The Nicolaus P-17 book is excellent. Yes, it’s “just” copies of the original drawings… but Nicolaus redrew most of them, and if you’re really going to use them instead of admiring them, they’ll keep you from going blind squinting at xeroxes of sepias.

Colvin & Viall’s “US Rifles and Machine Guns” is a hundred years old now, and it still has everything from blueprints to tolerances, heat treat, and details of the special machinery used to make the 1903 Springfield.

Oh, that’s one I didn’t know. I’ve been working on the references quoted in Chinn and Balleisen, but I’ve misplaced my copy of Balleisen.

Three additional issues in reverse engineering:

Gauges – Prior to World War II, authoritative dimensional tolerances for most American firearms parts were established by gauges, not drawings. This was the basis of the Eli Whitney devised ‘American System’ of manufacture. Engineering drawings were only created when parts were to be produced by outside contractors during WW II. Even then, gauges were often supplied to subcontractors and considered authoritative. Thus you must have some appreciation of the gaugemaster’s art to create engineering drawings which actually represent parts as they were produced by original manufacturers.

Metallurgy – No mention of metallurgy here, but metallurgical processes differed in detail and substance in the past. The differences from modern metallurgical practices increase the further your selected firearm dates back in time. Many of the 19th Century’s metallurgical practices are extinct, so efforts at metallurgical adaption is necessary. Modern metallurgy is indisputably better than vintage metallurgy, but it may not offer cosmetic satisfaction easily. Case in point: case hardening colors. Premium alloys and/or heat treatments may be necessary to compensate for labor intensive processes which are lost to history.

State of Development – Many of the most viscerally exciting firearms designs of the past were works in progress at the time of their production demise, thus were not fully developed. The late war German firearms such as the FG.42 and Gerat 05H are good examples here. An effort to reproduce such designs may inject you into the ‘development loop’ at the point the firearm went out of production. This can entail debugging costs the reproducer did not anticipate.

Brilliant points all, John.

To which I’d add —

Limits of CNC — Many people today assume that a CNC mill is an “anything machine” that can duplicate anything made in the past. Can’t, necessarily. (Case in point: M1 or M14 receiver). A lot of those things were made by a long chain of processes that involved such extinct (for all practical purposes) machinery such as shapers and horizontal mills with special, one-purpose cutters. As a rule of thumb there is always more than one way to make a cut, but it might not be an economical way.

Labor Intensivity — a worker today makes more per hours (in constant dollars) than his 19th or 20th Century ancestor. So new processes tend to remove as much benchwork, handwork and fitting — stuff that requires a trained eye and a skilled hand — from the loop as they can get away with.

Re your points: Metallurgy continues to evolve and the best steels of 2014 are not the ones spec’d by Armalite in 1954, Springfield in 1934, or DWM in 1914. Also, US and Continental metallurgy (and many other practices) were widely divergent under the regnant SAE, etc., and DIN norms. The Japanese also had their own system which took into account the limits of the steel industry in their resource-poor nation. Re, State of Development: in most cases a military firearm is a work in progress, to some extent, through its whole life cycle. Note the difference between 1950s M1 Garands and early wartime guns; now details that speak to collectors, then those were a system of continuous improvement, not exactly Kaizen but something similar.

Thank you for a really solid, on point and educational comment, John!

Worst metallurgical problems for today’s firearms reproducers are springs, specifically leaf and spiral (clockwork) springs. The technology for making these springs has fallen by the wayside and manufacturers of these types of springs are few and far between today. Probably why no one has attempted to reproduce the Lewis gun, and why there are a lot of floppy cocking handles on 20mm Lahti antitank rifles.

Round wire springs today are much better than their counterparts made before and during WW II.

I can’t believe that a reverse engineered baby Nambu or .45 Luger would be significantly more expensive than a new Colt Lightning. I point to the Erma baby Luger and Chinese .45 broomhandles of the 1980s.

The reverse engineered Colt 1903s will retail at $1000 or so. There will be a thousand of them, which suggests $700,000 as a cost for the run. That price is high for a copy of a gun for which decent originals run $5-700.

Someone is missing a bet not tooling up for a thousand Borchardts or Savage .45s at $2500 each.

I don’t think you could make the Borchardt or even the Luger to original quality for $2500 in direct cost, never mind overhead and marketing. The Savage, maybe. Mauser’s latter runs of Lugers were made with original (Swiss) tooling.

Maybe not, I’m no production man. Just trying to extrapolate from other things. You can buy a lawn tractor or ATV for $2500 retail, and new BARs and FG-42s are lose to $5000. I picked $2500 because that seems to be a fairly reasonable “toy” price these days, and there are plenty of ordinary production guns that approach or exceed that price and must be selling.

But the idea is still good, there’s a profit out there for someone who wants to front a million or so.