Archaeologists are always surprised to find that historical information from contemporary sources, pamphlets, or news stories is confirmed by the results of a dig (probably because they read the New York Times and watch TV news and assume today’s media is fabulistic, in the tradition of yesterday’s). The latest unexpected discovery is this cannon shard which from a New Jersey dig which seems to confirm some details of the October, 1777 Battle of Red Bank, a small but dramatic Continental victory, in which attacking Hessian mercenaries suffered extreme casualties under an artillery and small arms barrage, and the American casualties were light, comprising primarily a single gun crew slain when the gun exploded.

Historians who studied the Battle of Red Bank in 1777 have long known the tragic story of an American gun crew.

It was one of several defending Fort Mercer against a much larger army of Hessian soldiers, who were trying to dislodge them and open up the Delaware River for British ships to supply the Redcoats occupying Philadelphia.

The crew loaded a massive cannon, lit the fuse, and fired – but the breech exploded, killing a dozen members of Rhode Island regiments who were manning the gun and earthworks.

The battle, while a Continental victory, took place amid a series of strategic setbacks and defeats. Washington’s objective had been to cut off Philadelphia as he had in the previous year cut off Boston and forced a British defeat, and much as later in 1776 the British had forced him out of New York. To that end, the campaign that began with the upset of Hessian forces at Princeton and Trenton in December ’76 gave way to a plan to ring Philadelphia round with a number of fortifications. But Washington was in a weak position; he had to be strong at every fort, and he just didn’t have the men. The British, on the other hand, could use the Royal Navy to bring overwhelming force to one fort at a time, as they were not placed well for mutual support.

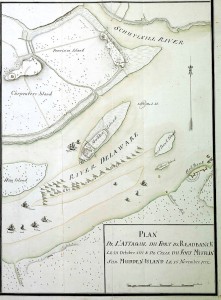

Hessian Map of the Battle Area. Fort Red Bank at lower right. As was customary in the 18th Century (under Vauban’s influence), the map’s legend is in French, which both the English and German officers could understand.

The fortifications at Red Bank were part of this ring around Philadelphia, which British forces had been rolling up through the summer and fall of 1777. A fort named Fort Mifflin stood on a rather insubstantial island in the Delaware called (appropriately) Mud Island, toward the Pennsylvania side; the fort on the Jersey side (in or just south of modern Camden, NJ) was called Fort Mercer (named after Brigadier General Hugh Mercer, a doctor turned warrior who died of wounds from the Battle of Princeton in January, 1777), but not knowing that name, the British called it Red Bank. The forts guarded water obstacles, chevaux-de-frise, and covered those obstacles with the observation and fires necessary to prevent English engineers from dismantling the blockages. To achieve Lord Howe’s strategic objective of the relief of Philadelphia, these forts had to go.

It was Red Bank’s turn to be reduced by amphibious attack on 21 October 1777. The operation was a success, in that the British took the ground they sought; but it was a costly success. First, here’s the commanding officer’s spin. This is the report of the British commander, General Sir William Howe, in a letter he wrote to Lord George Germaine from Philadelphia on 25 October 1777.

My Lord,

The enemy having intrenched about 100 men at Red-Bank, upon the Jersey shore, some little distance above Fort Island, Colonel Donop, with three battalions of Hessian grenadiers, the regiment of Mirback, and the infantry, Chasseurs, crossed the Delaware on the 21st instant to Cooper’s Ferry, opposite to this town, with directions to proceed to the attack of that post. The detachment marched a part of the way on the same day, and on the 22nd in the afternoon was before Red Bank; Colonel Donop immediately made the best disposition, and led the troops in the most gallant manner to the assault. They carried an extensive outwork, from which the enemy were driven into an interior intrenchment, which could not be forced without ladders, being eight or nine feet high, with the parapet boarded and fraized. The detachment in moving up, and returning from, the attack, was much galled by the enemy’s gallies and floating batteries.

Colonel Donop and Lieutenant Colonel Minningerode being both wounded, the command devolved upon the Lieutenant Colonel Linsing, who after collecting all the wounded that could be brought off, marched that night about 5 miles towards Cooper’s ferry, and on the following morning returned with the detachment to camp.

Colonel Donop unfortunately had his thigh so much fractured by a musket ball, that he could not be removed; but I since I understand there are some hopes of his recovery. There were several brave Officers lost upon this occasion, in which the utmost ardour and coverage or displayed by both officers and soldiers.

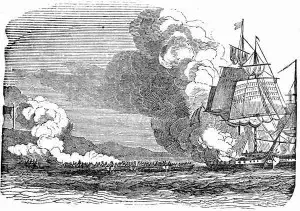

On the 23rd, the Augusta, in coming up the river with some other ships of war, to engage the enemies gallies near the Fort, got a-ground and by some accident taking fire in the action, was unavoidably consumed; but I do not hear there were any lives lost. The Merlin sloop also grounded, and the other ships being obliged to remove a distance from the explosion of the Augusta, it became expedient to evacuate and burn her also.

These disappointments, however, will not prevent the most vigorous measures being pursued for the reduction of the Fort, which will give us the passage of the river.

I have the honor to be, &c.

W. Howe.

PS I have the satisfaction to enclose to your Lordship a report just received a very spirited piece of service performed by Major-General Vaughn and Sir James Wallace up the Hudson’s river.

We’d planned on stopping the excerpt here, because Vaughan’s report doesn’t bear directly on the Red Bank fight and the attempted (and ultimately successful) relief of Philadelphia by Crown forces, but we know you guys would ask, and it’s a brief report, and illuminative of Vaughan’s character so here it is:

Copy of Major General Vons report. On board the friendship, off Esopus, Friday, October 17, 10 o’clock, Morning.

Sir,

I have the honor to inform you, that on the evening of the 15th instant I arrived off Esopus; finding that the rebels had thrown up works, and had made every disposition to annoy us, and cut off every communication, I judged it necessary to attack them, the wind being at that time so much against us, we could make no way. I accordingly when did the troops, attacked their batteries, drove them from their works, spiked and destroyed their guns. Esopus being a nursery for almost every villain in the country, I judged it necessary to proceed to that town. On our approach they were drawn up with cannon, which we took, and drove them out of the place. On our entering the town they fired from their houses, which induced me to reduce the place to ashes, which I accordingly did, not leaving a house. We found a considerable quantity of stores of all kinds, which shared the same fate.Sir James Wallace has destroyed all the shipping except an armed galley, which run up the creek, with everything belonging to the vessels in store.

Our loss is so inconsiderable, this is not at present worthwhile to mention.

I am, &c.

John Vaughn

Esopus, New York, burned by Vaughan’s forces, was the initial capital of the state in rebelliion, so Vaughan’s irritation with the town was on solid ground. The name dated to Colonial Dutch times; when the city was rebuilt it was (and is) known as Kingston, NY. The Esopus fight was much more a British victory than was Red Bank, despite Lord Viscount Howe’s spin in his report above.

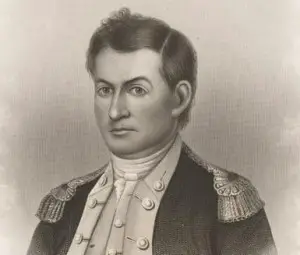

At Red Bank, the Hessians drew up and demanded a surrender, threatening no quarter. The militia in the fort, under the command of Colonel Christopher Greene, defied the threat and informed the Hessians that no quarter would be given to them. (In the end, it was, and the militia did not murder their prisoners).

At Red Bank, the Hessians drew up and demanded a surrender, threatening no quarter. The militia in the fort, under the command of Colonel Christopher Greene, defied the threat and informed the Hessians that no quarter would be given to them. (In the end, it was, and the militia did not murder their prisoners).

The colonials at Red Bank retreated in good order and their primary losses were the gun crew killed by the explosion of the gun; the Hessians suffered hundreds of casualties. But Red Bank was the exception; one after another the British forces levered the Yankees out of their positions and opened the sea roads to Philadelphia.

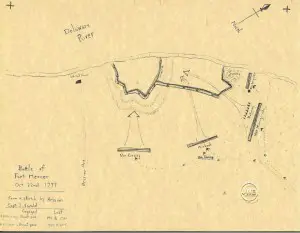

The Reduction of Fort Mercer at Red Bank. Modern sketch from a period Hessian sketch by Capt. J. Ewald. The New Jersey militiamen escaped to the left of this sketch (southwest) after killing and wounding 325-400 Hessians. On withdrawal, the Hessians abandoned their wounded who joined other Hessians as prisoners, also.

Howe’s report is full of spin. He tends to minimize casualties; for example, Colonel von Donop of the Hessians was in no way on the path to recovery, and he shortly died, and while he lists officer casualties in detail he evidences little interest in enlisted casualties, especially among the German mercenaries and local auxiliaries that were the bulk of his force. And he probably knew well that the two ships he lost were lost because of Continental obstacles, and the Augusta (a 64-gun ship of the line) was burnt by American fireships.

The house the Continentals used for their headquarters and hospital, and in which von Donop was treated a prisoner, still stands and is part of the Red Bank National Historic Site. (Von Donop was removed to another house, where he expired from his wounds three days later).

There is a ghost story involving Hessians with mismatched heads.

The surviving Hessians, beaten back by musketry and cannon fire, exfiltrated overland to Woodbury, leaving their casualties behind. The question of Hessians that died with their boots (and heads) still on was one of the things that motivated the modern archaeologists, who descended on the popular park this summer, and they did find buttons and bone fragments that indicate that they may have found a mass grave of the unfortunate Germans. (More analysis of the bones is required before that can be stated as fact).

But the most interesting discovery is a large fragment of a cannon breech, taken as being the one that exploded during the battle (we would need to see more documents to make sure the Hessians did not capture and blow up guns also, as it could have been one of those). Still, the archaeological team was not expecting such a historic find.

But the most interesting discovery is a large fragment of a cannon breech, taken as being the one that exploded during the battle (we would need to see more documents to make sure the Hessians did not capture and blow up guns also, as it could have been one of those). Still, the archaeological team was not expecting such a historic find.

In the end, Howe kept coming, and he occupied Fort Mifflin on 16 November and Fort Mercer — finally abandoned by the Americans after the fall of Mifflin — on 20 November, 1777. The defenders had bought time, bled the occupying army, and most of them had slipped away to fight another day. Before they could do that, the privations of their winter in Valley Forge lay ahead.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

2 thoughts on “Archaeology Find Confirms 1777 Battle Story”

probably because they read the New York Times and watch TV news and assume yesterday’s media was fabulistic, in the tradition of today’s.

Fixed it. And undoubtedly so.

It would be fascinating to find a piece of history like that. I see the goofy shows about metal detectorists and think it’s neat but what they don’t say is how removing the items and not effectively documenting the locations, depth, etc, removes them from their historical context. So in this respect I’m glad an organized archeological dig found them to preserve their identity.