In 1967, the Army got the idea to study whether, how, and how effectively different units were using snipers in Vietnam. They restricted this study to Army units, and conventional units at that; if SF and SOG were sniping, they didn’t want to know (and, indeed, there’s little news either in the historical record or in conversations with surviving veterans that special operations units made much use of precision rifle fire, or of the other capabilities of snipers).

Meanwhile, of course, the Marines were conducting parallel development in what would become the nation’s premier sniper capability, until the Army got their finger out in the 1980s and developed one with similar strength. The Marines’ developments are mentioned only in passing in the study.

Specific Weapons

The study observed several different sniper weapons in use:

- ordinary M16A1 rifles with commercial Realist-made scopes. This is the same 3×20 scope made by Realist for commercial sale under the Colt name, and was marked Made in USA. (Image is a clone, from ARFCOM).

- Winchester Model 70s in .30-06 with a mix of Weaver and Bushnell scopes, purchased by one infantry brigade;

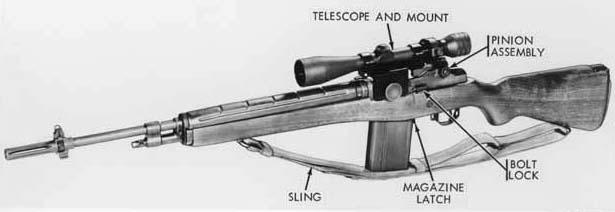

- two versions of the M14 rifle. One was what we’d call today a DMR rifle, fitted with carefully chosen parts and perhaps given a trigger job, and an M84 scope. The other was the larva of the M21 project: a fully-configured National Match M14 fitted with a Leatherwood ART Automatic-Ranging Telescope, which was at this early date an adaptation of a Redfield 3-9 power scope. (Image is a semi clone with a surplus ART, found on the net).

The scopes had a problem that would be unfamiliar to today’s ACOG and Elcan-sighted troopies.

The most significant equipment problem during the evaluation in Vietnam was moisture seepage into telescopes. At the end of the evaluation period, 84 snipers completed questionnaires related to their equipment. Forty-four of the snipers reported that their telescopes developed internal moisture or fog during the evaluation period. In approximately 90 percent of the cases, the internal moisture could be removed by placing the telescope in direct sunlight for a few hours.

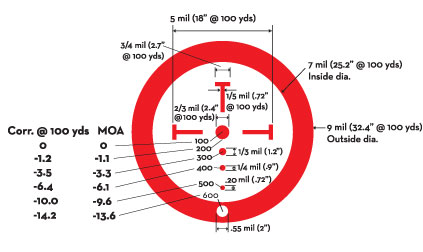

The leaky scopes ranged from 41% of the ARTs to 62% of the Realists. The Realist was not popular at all, and part of the reason was its very peculiar reticle. How peculiar? Have a look.

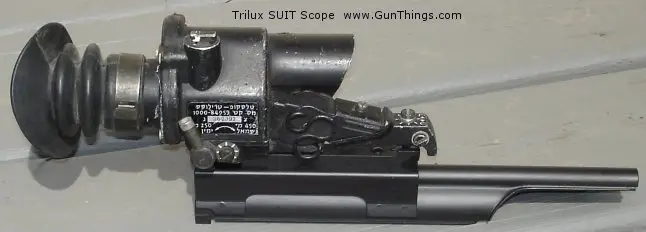

(A later version of this scope, sold by Armalite with the AR-180, added feather-thin crosshairs to the inverted post. The British Trilux aka SUIT used a similar inverted post, but it never caught on here).

(A later version of this scope, sold by Armalite with the AR-180, added feather-thin crosshairs to the inverted post. The British Trilux aka SUIT used a similar inverted post, but it never caught on here).

The theory was that the post would not obscure the target, the way it would if it were bottom-up. That’s one of the ones you file away in the, “It seemed like a good idea at the time,” drawer. Theory be damned, the troops hated it.

The use of the rifles varied unit by unit. Two units contemptuously dismissed the scoped M16s, and wouldn’t even try them (remember, this was the era of M193 ammo, rifles ruined by “industrial action,” and somewhat loose acceptance standards; the AR of 20145 is not the AR of 1965). The proto-M21s came late and not every unit got them. It’s interesting that none of the weapons really stood out, although the NATO and .30-06 guns were the ones used for the longest shots.

None of the weapons was optimum, but in the study authors’ opinion, the DMR version of the M14 was perfectly adequate and available in channels. The snipers’ own opinions were surveyed, and the most popular weapon was the M14 National Match with ART scope, despite its small sample size: 100% of the surveyed soldiers who used it had confidence in it. On the other hand, the cast scope rings were prone to breakage.

The biggest maintenance problem turned out to be the COTS Winchester 70 rifles, and the problem manifested as an absence of spare parts for the nonstandard firearm, and lack of any training for armorers.

Looking at all the targets the experimental units engaged, they concluded that a weapon with a 600 meter effective range could service 95% of the sniper targets encountered in Vietnam, and that a 1000 meter effective range would be needed to bag up to 98%. (Only one unit in the study engaged targets more distant than 1000 m at all).

Snipers were generally selected locally, trained by their units (if at all), and employed as an organic element of rifle platoons. A few units seem to have attached snipers to long-range patrol teams, or used the snipers as an attached asset, like a machine-gun or mortar team from the battalion’s Weapons Company.

An appendix from the USAMTU had a thorough run-down on available scopes, and concluded with these recommendations (emphasis ours):

Recommendations:

a. That the M-14, accurized to National Match specifications, be used as the basic sniping rifle.b. That National Match ammunition be used in caliber 7.62 NATO.

c. That a reticle similar to Type “E” be used on telescopic sights of fixed power.

d. That the Redfield six power “Leatherwood” system telescope be used by snipers above basic unit level.

e. That the Redfield four power (not mentioned previously) be utilized by the sniper at squad level.

f. That serious consideration be given to the development of a long range sniping rifle using the .50 caliber machine gun cartridge and target-type telescope.

(NOTE: It is our opinion that the Redfield telescope sights are the finest of American made telescopes.)

Note that the Army adopted the NM M14 with ART (as the M-21 sniper system) exactly as recommended here, but that it did not act on the .50 caliber sniper system idea. That would take Ronnie Barrett to do, quite a few years later.

The Effects of Terrain

Terrain drives weapons employment, and snipers need, above all, two elements of terrain to operate effectively: observation and fields of fire. Their observation has to overlook enemy key terrain and/or avenues of approach. Without that, a sniper is just another rifleman, and snipers were found to be not worth the effort in the heavily vegetated southern area of Vietnam.

In the more open rice fields and mountains, there was more scope for sniper employment. But sniper employment was not something officers had been trained in or practiced.

The Effects of Leadership

In a careful review of the study, we found that the effects of leadership, of that good old Command Emphasis, were greater than any effects of equipment or even of terrain. The unit that had been getting good results with the Winchesters kept getting good results. One suspects that they’d have continued getting good results even if you took their rifles away entirely and issued each man a pilum or sarissa.

Units that made a desultory effort got crap for results. Some units’ snipers spent a lot of time in the field, but never engaged the enemy. Others engaged the enemy, but didn’t hit them, raising the question, “Who made these blind guys snipers?” Sure, we understand a little buck fever, but one unit’s snipers took 20 shots at relatively close range and hit exactly nothing. Guys, that’s not sniping, that’s fireworks.

The entire study is a quick read and it will let you know just how dark the night for American sniping was in the mid-1960s: there were no schools, no syllabi, no type-standardized sniper weapons, and underlying the whole forest of “nos” was: no doctrine to speak of.

Vietnam Sniper Study PB2004101628.pdf

Is it Time to Scope Out Scopes?

Iron sights are obsolete. Britain saw this one, and acted on it, before the United States did. (So did Germany, even earlier; but then they backed off). The plain truth is that iron sights are obsolete, outdated, dead; they’re not just resting or pining for the fjords. They’ve shuffled off their mortal coil and joined the Choir Invisible.

Iron sights are obsolete. Britain saw this one, and acted on it, before the United States did. (So did Germany, even earlier; but then they backed off). The plain truth is that iron sights are obsolete, outdated, dead; they’re not just resting or pining for the fjords. They’ve shuffled off their mortal coil and joined the Choir Invisible.

They’re dead, Jim.

As a shooter, you should still understand and be able to use the many kinds of iron sights that have been used on rifles, pistols, and machine guns over the last few centuries. The shooting fundamentals work the same (with the self-evident exception of sight picture and sight alignment) regardless of what kind of sight you’re using, but the iron sight imposes physical, temporal and human factors obstacles that optical sights do not.

The most important of these factors is that an optical sight, whether it’s a traditional telescope, a red-dot, or a holographic sight, puts the aiming point and the target in the same focal plane. How important is this? It’s vital. It reduces the time spent to align the shot (more than compensating for the initial delay imposed by a magnified sight with a limited field of view, it lightens the shooters neurocognitive load, and it reduces hit dispersion downrange.

It’s the nature of a human eye that, unlike a camera, its an extremely complicated piece of hardware that is normally used in pairs to collect a dynamic and changing amount of light that is resolved, not upon the focal plane of a retina, but by the software of a brain resolving, merging and interpolating light data.

Unlike a camera, where the focal plane is just that, a plane, a retina is curved. Unlike a camera, where one pixel receptor of a charge-coupled device (or traditionally, one chemical grain of film coating) resolves the same shades or colors and responds the same to a given amount of light towards the periphery as its companion does at the center, our retinal cells are not all the same. The different kinds, which respond differently to light and color, are distributed unevenly. Unlike a camera, the human visual mechanism with its two eyes, brain, and “software”-driven focus is, at once, a wide-angle lens (with pretty lousy off-axis resolution, but good for movement) and a telephoto (which can perceive great detail, but only straight on).

And unlike a camera, human depth of field is not variable, although the location of focus is. What this means is that you can’t simultaneously focus on the front sight, the rear sight, and the target. Well the most important of those three items is the target, with iron sights you’re likely to miss it if you don’t focus on the front sight. Shooters must be trained (and must practice) to focus on the front sight like that.

So the eye is an awesome piece of engineering (or engineered hardware/software integrated system, really). But it has its limits. In optic land, your aiming point (whether it’s a dot or a crosshair) is superimposed on your target, in a single focal plane. Again, you must train for this, but it takes less training, and it leads to a more rapidly acquired sight.

The aiming point can be a crosshair, another reticle, or an illuminated dot. Each has its pros and cons. For rapid training it’s very difficult to beat the red dot. For distance shooting, numerous compensated reticles are available. Some sights try to provide both: any sight with a complicated reticle rewards study, understanding, and practice.

The military forces of the world have been slow in seeing this and issuing optics on a general, wide-scale basis. In fact, it’s taken most of a century for them to catch on worldwide. Before they were able to do so, of course, optics needed to improve: first they needed to be weather-sealed and fog-resistant (first achieved just before WWII), then needed coated optics for improved light transmission, and finally they needed to be ruggedized, or grunt-proofed, if you will. This last is not a small task, as the grunts of any army you could name take a perverse pride in their ability to destroy flimsy gear, and their definition of “flimsy” is eye-opening, if you are not a grunt.

Now, the armies of the world understood the benefits of optics for various artillery, aviation, and even machine-gun uses. (The US issued a dreadful Warner & Swasey telescopic sight for the Benet-Mercié Machine Rifle of 1909; the Imperial Japanese Army had scopes for the Type 92 (1932) medium and Type 96 (1936) light machine guns.

Germany started to do it in World War II, but they lost the war before they could universalize their general-purpose infantry optic, the ZF41. (ZF41, seen here on an FG42, was more common on G.43 and MP/STG.44 type weapons).

After the war, the Federal Republic was slow to adopt optics again, but by the 1960s was issuing a Hensoldt scope to designated marksmen. The current G.36 has its issues, but is optics-ready and issued with a range of optical sights.

Britain, bruised by international opinion, introduced a low-magnification, lighted-reticle optic in 1973, first in Northern Ireland for designated marksmen, then throuhgout the British Army. It never achieved universal issue, but its successor, the SUSAT for the problematical SA.80 rifle, did.

This SUIT (Trilux) sight appears identical to the UK model, but is marked in Hebrew. Gee, wonder who used it?

Meanwhile, in 1977 the Austrian Army adopted the revolutionary Stg.77, known to the world as the AUG (Armee Universal-Gewehr), its trade name. The AUG was a bullpup design with a 1.5 power optic in an M16-like carrying handle, with rude backup sights on top of the scope housing. (Later AUGs used standard, rail-mounted modular optics).

In the 1980s, Canada issued the domestic Elcan C79 as standard on their new rifle, the Diemaco (later Colt Canada) C7, and the C9 general purpose machine gun. The US Army, whose motto in small arms sometimes seems to be “First? Us? Never!” adopted this sight as the M145 Machine Gun Optic (MGO). US SOF drove the adoption of optics in the 1990s, formalizing what had been a lot of single-unit experiments with the circa 2000 SOPMOD initiative. SOPMOD I saw the first version of the Aimpoint M68 and the Trijicon ACOG adopted. (General purpose forces adopted these optics, or improvements on them, very quickly thereafter).

Russian and Chinese forces are seen more and more frequently with optics and with modular sighting equipment.

If you’re still aiming with a peep or open rear sight and a bead or post up front, good for you. It’s great for marksmanship basics. But small arms history is leaving you behind. It’s time to scope out some scopes.

The Case of the Bargain Optics, 1964

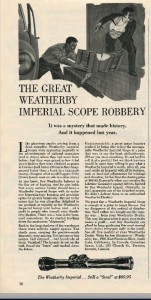

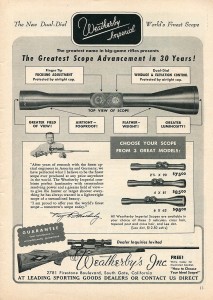

Like phantom smoke arising from a dead campfire, Weatherby Imperial Scopes were appearing magically in the advertisements of national magazines (and in stores) where they had never been before. And they were priced so low it led you to believe they were obtained as prizes in Cracker-Jack boxes. Of course they disappeared faster than a buck in a tamarack swamp. (Imagine what would happen if the Crown Jewels went on sale in a dime store.)

As you know, Roy Weatherby believes in the fine art of hunting. And he also holds that every serious hunter should have a Weatherby Imperial Scope with its exclusive binocular-type focusing and precision optics for greater luminosity. But not to the extent that he was altogether delighted to see products as superior as the Weatherby Imperial being sold below cost … at a profit to people who weren’t even Weatherby Dealers. There was a bear in the barnyard somewhere. So we started tracking down the mysterious “shipments.”

Back in the long shadows of the warehouse there were telltale, empty spaces. The sturdy cases, carrying the precision-made Imperials, were missing. Not just one or two scopes had skipped … but hundreds of them. Vanished! The hounds lit out on the trail, found the “fence” and tracked down the felons.

Understandably, a great many hunters profited by being able to buy the incomparable Weatherby Imperial Scope at a price that was, to say the least, philanthropic. (When you steal something, it’s not hard to sell it at a profit.) But we think hunters would be more than willing to pay what a Weatherby Imperial is worth. After all, you can’t make an Imperial with all its features, such as dual-dial adjustments for windage and elevation, for less than the starting price of $69.95. Especially when you consider the Lifetime Guarantee against defects, backed by Roy Weatherby himself. (Naturally, he can’t guarantee any of the hi-jacked scopes. He didn’t deliver them to an authorized Weatherby Dealer.)

We grant that a Weatherby Imperial Scope is enough of a prize to tempt thieves. But we disapprove of this method of distribution. We’d rather you bought one the regular way … from your Weatherby Dealer. This way, the guarantee is good, your dealer makes a profit…and Roy Weatherby can afford to keep producing this most wanted (even stolen) telescopic sight in the world. See all five models at your Weatherby Dealer.

This ad ran 50 years ago, in 1964. For example, it’s on Page 16 of the October, 1964 Guns magazine. Those old magazines are a trip, and an education: a trip in time travel, and an education in how much the gun culture has changed in a half-century.

It’s a general commonplace that the stories in magazines tend to be more descriptive, and the ads tend to be aspirational. In 1964, Weatherby was a premium brand, as the price of $70 in dollars that predate the guns-and-butter inflation of the LBJ 1960s and the gross economic mismanagement of all three of the 1970s Presidents. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ inflation calculator, the 2014 equivalent of that scope’s list price is $532.86, so in real purchasing-power terms, the price of a quality scope hasn’t changed much.

Of course, the $500 scope of today will be better than a Weatherby Imperial of the LBJ years on several axes of measurement. The 1960s scope most often has a very fine crosshair reticle, which evaporates in low light.

The Imperial scope had some unusual features that were unique then and are still a bit odd by today’s standards. It had two turrets, both at 12 o’clock and so close as to be conjoined, almost siamesed, with nested knobs or rings in the forward turret for fine adjustments (inner was windage, outer elevation) and one knob in the after turret for focus. Gross adjustments were done with the scope base screws when setting the scope up, so as not to use up too much travel and/or get the reticle out of center of the scope whilst getting sighted-in.

The Imperial scope had some unusual features that were unique then and are still a bit odd by today’s standards. It had two turrets, both at 12 o’clock and so close as to be conjoined, almost siamesed, with nested knobs or rings in the forward turret for fine adjustments (inner was windage, outer elevation) and one knob in the after turret for focus. Gross adjustments were done with the scope base screws when setting the scope up, so as not to use up too much travel and/or get the reticle out of center of the scope whilst getting sighted-in.

Weatherby never made scopes themselves, but they had private brand scopes made with the Weatherby name for 40 years, from 1954 to 1994. In 1954, Roy Weatherby himself selected Hertel & Reuss of Kassel, West Germany; after visiting several other scope factories, he thought the Kassel company had the best handle on producing quality optics.

The Imperial scope was made in several magnification ranges by Hertel & Reuss from 1954 to 1973, when it was replaced by the Premier line, made by Asia Optical in Japan. The Premier scopes were renamed Supreme in 1983. Asia Optic also made the Mark XXI scope from 1964 to 1989.

Hertel & Reuss was founded by Otto Hertel and Eduard Reuss in 1927. As a maker of all kinds of optics, it survived the Weimar Republic, the Third Reich and its defeat, and the rocky dawn of the Federal Republic — even German Reunification in 1992. But the company had left the rifle-scope market well before it ceased trading in 1995. A successor company owns the Hertel & Reuss trademark and applies it to opera glasses made in the old university town of Marburg. The original Hertel & Reuss plant, where the Weatherby riflescopes and other precision optics were made, now is a European call center for the schlock TV sales outfit, QVC.

This sharp .300 Weatherby Magnum was sold from South Gate, California, and is a German Mauser action topped by an Imperial scope in Buehler mounts. It has (in our humble opinion) much more classic lines and trim than some of the more over-the-top Weatherbys. A well-used elk gun, but still beautiful; this picture is from a closed auction at GunAuction.com. (Our basic training drill sergeant, Vietnam vet Antenor “Tony” Arguello, was a Weatherby fan. Wonder how he’s doing these days?)

Weatherby Imperials are the most-sought Weatherby scopes by Weatherby collectors. You may hear the sentiment that a German Weatherby rifle ought to have a German Weatherby scope. But the scopes are not worth a king’s ransom; a used, good-condition Imperial sells for $200-300, max. One not in good condition is just about worthless.

Gilbert Parson of Parson’s Scope Service (aka Parson’s Optical Manufacturing) in Ross, Ohio can still service the Imperial scopes; ABO Inc, in Miami, can handle Weatherby’s Japanese scopes. But given the advances in the last 50 years and the high cost of skilled repairs, it may be wiser to replace rather than repair these old warhorses.

What’s the Opposite of “Advanced”?

We leave answering the question as an exercise for the reader after watching this video, about 15 minutes long. Here you see the 1989-90 contenders for the Advanced Combat Rifle, a program that would have replaced the issue M16A2 rifle which was still being fielded into some low-priority units, replacing 20-25 year old M16A1s, at the time.

The video begins with a rather sloppy three-minute history of American infantry weapons (you’ll cringe at the assertion that the first Army bolt-action was “made by Krag-Jorgensen,” or that the 1903 Springfield “wasn’t much better than the Krag.” The video also makes a curious claim — one not seen in the doctrinal literature — that the M16A2 had an effective range of 550 meters.

The reason for the program is explained: the actual combat accuracy of the rifle in soldiers’ hands degrades far below its mechanical potential. So the ACR program was hoping to double the real-world effectiveness of the individual weapon.

The four vendors trying to grab the contractual brass ring were:

- AAI, with a flechette-firing M16 cousin, complete with early ACOG;

- Colt, with a product-improved M16, including an adjustable carbine-like stock, four-position selector, duplex (two-bullet) ammunition, and an available Elcan scope (similar to the model later adopted as the M145 machine-gun optic);

- H&K, with an Americanized version of their ill-fated caseless G11; and,

- Steyr-Mannlicher, with an oddball AUG derivative firing polymer-cased rounds with flechette projectiles.

At about 10 minutes in, the video presents the modifications made to Buckner Range on Fort Benning to evaluate the novel weapons.

In the end, none of them was sufficiently superior to the issue M16A2, or sufficiently well-developed already, to justify further development.

We thought for sure we’d put this video up before, but while we’ve talked about some other boneheaded procurement events — like in this post on the Objective Family of Weapons two years ago — we don’t appear to have actually done it.

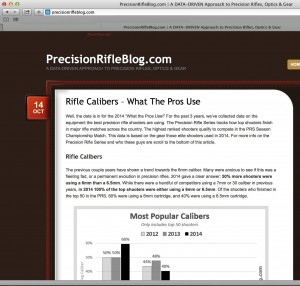

Wednesday Weapons Website of the Week: Precision Rifle Blog

We don’t know how we missed this guy, PrecisionRifleBlog.com, until now. As long time readers know, we have always admired the empirical, side-by-side A-B testing, like the tests that Andrew Tuohy carried out on his own website, Vuurwapen blog, and later at the sadly moribund Lucky Gunner Labs and The Firearm Blog (just search for his name on those sites — if he did it, it’s good. He’s a young man, but he has his stuff in one bag). It reminds us of a scientific experiment. In the same vein, we have enjoyed some of the experiments that Phil Dater PhD did with barrel length, muzzle velocity, and sound pressure levels. Science FTW!

We don’t know how we missed this guy, PrecisionRifleBlog.com, until now. As long time readers know, we have always admired the empirical, side-by-side A-B testing, like the tests that Andrew Tuohy carried out on his own website, Vuurwapen blog, and later at the sadly moribund Lucky Gunner Labs and The Firearm Blog (just search for his name on those sites — if he did it, it’s good. He’s a young man, but he has his stuff in one bag). It reminds us of a scientific experiment. In the same vein, we have enjoyed some of the experiments that Phil Dater PhD did with barrel length, muzzle velocity, and sound pressure levels. Science FTW!

Now, wouldn’t it be neat if somebody did something like that with rifle scopes, among other precision rifle data sets? Turns out, somebody has; his name is Cal Zant and his website, Precision Rifle Blog, promises “a data-driven approach” to long-range, precision shooting. Cal delivers that, in spades. That’s why he’s the Wednesday Weapons Website of the Week.

Let’s show you one example of his coolest recent research, an incredible comparison test of high-end rifle scopes. These are the sort of scopes you’d apply to a precision rifle for target, hunting, or war. He has conducted a well-planned and thorough battery of tests of 18 high-end scopes, side-by-side, using a pretty solid array of methodologies. Then, he ranked the scopes according to a weighting scheme that he worked out based on what respondents to a survey said was important.

Every step of his way, he shows his work. Disagree with his weighting scheme? All the data are there; you can draft your own and see how that changes the ranks. Some features are not important to you? Delete them from the weighting scheme and recalculate. The data are all there, and will cost you only the considerable time needed to read and consider them.

The two essential links are to the Field Test Results Summary and the Buyers Guide and Features to Look For.

But those alone don’t tell the whole story, because he’s also included in-depth links and all his methodologies. Not surprising in the STEM world, especially in engineering, the end of STEM furthest from all the theory. And even if you read all the links, you may have further questions, especially if you’re not well-versed in optics terminology. (We thought we were; the site disabused us of that notion right smartly). So he provides an extremely useful online glossary. Confused by the difference between miliradian-based (Mil) and minute-of-angle (MOA) reticles? He’s not, and you won’t be either, if you read his page on the subject. (Short version: if you’re a yards-and-inches guy, you might be happier with MOA, if you’re metricated, you’ll want a mil reticle and turrets).

You can quibble with the weighting scheme, or bellyache that your favorite scope was not included, but we’re still just struggling with the disbelief of the whole thing: that someone would do all this work for nothing but the pleasure of doing it, and then bestow it on the rest of us.

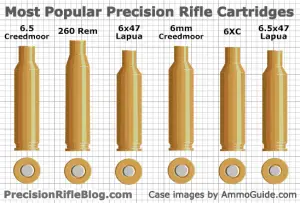

At this point, you might think that Precision Rifle is all about scopes, and it’s not. That’s just an example of what he’s got for you over there. Here’s another example — a chart from a long article on the calibers most used by National Championships’ top 50 competitive shooters. It’s interesting that the question of caliber is now down to 6 or 6½ millimeters, at least among top 50 competitors. We didn’t know that before reading it on Precision Rifle.

At this point, you might think that Precision Rifle is all about scopes, and it’s not. That’s just an example of what he’s got for you over there. Here’s another example — a chart from a long article on the calibers most used by National Championships’ top 50 competitive shooters. It’s interesting that the question of caliber is now down to 6 or 6½ millimeters, at least among top 50 competitors. We didn’t know that before reading it on Precision Rifle.

Go, and return smarter, grasshoppers.

What TrackingPoint Must Do to Sell to SOF

![]() We think the guys running TrackingPoint know what they have to do. In fact, we think they’re already doing these things. But here’s what, from our point of view, is missing from the current iteration of TrackingPoint hardware and software for real penetration into the upper tier SOF market.

We think the guys running TrackingPoint know what they have to do. In fact, we think they’re already doing these things. But here’s what, from our point of view, is missing from the current iteration of TrackingPoint hardware and software for real penetration into the upper tier SOF market.

So, Who Do You Hit First?

If we were their marketing consultants (we use our MBA, but not like that), we’d also press them to focus on sell-in to certain SOF elements that are image leaders in the international SOF community. Sell, for example, to SAS, and you will have Peru, the UAE, the Netherlands, and many other nations very interested in your product line (Indeed, sell to SAS or to their US counterparts, and you’ll get sale after sale, worldwide). It’s important, also, not to over-discount the stuff to your lead customers: confidentiality agreements are fine and good, but they probably can’t keep, say, American shooters from telling the foreign shooters they’re training with or competing against, what a good deal you gave ’em.

If we were their marketing consultants (we use our MBA, but not like that), we’d also press them to focus on sell-in to certain SOF elements that are image leaders in the international SOF community. Sell, for example, to SAS, and you will have Peru, the UAE, the Netherlands, and many other nations very interested in your product line (Indeed, sell to SAS or to their US counterparts, and you’ll get sale after sale, worldwide). It’s important, also, not to over-discount the stuff to your lead customers: confidentiality agreements are fine and good, but they probably can’t keep, say, American shooters from telling the foreign shooters they’re training with or competing against, what a good deal you gave ’em.

Another possible launch customer is FBI HRT. As their history of reckless shots and whacked non-targets shows, they could use the marksmanship boost. Meanwhile, despite their record, they’re very influential on local police procurement. Tag/track/release technology is just the ticket for police marksmen who never get enough time for training, and yet have to make more consequential and more constrained shots than a lot of military snipers. (A military sniper, outside of some rarefied CT or HR gigs, almost always has the option to no-shoot. FBI or police sniper, scope-on a crim threatening a hostage, might lack that luxury).

Who Don’t You Hit?

While the Marine Scout Snipers could use the hell out of this thing, it’s too foreign to Marine marksmanship culture, which is a master-and-apprentice culture that demands effort, even hardship, and eschews automation or corner-cutting of any kind. So we’d put these excellent Marine precision marksmen way down the list, right now. We’ve worked with enough 8541s to know that they like to do things the hard way, and they take particular joy in doing it the hard way faster than an Army guy can do it the easy way, and take a positively indecent glee in breaking the dogface’s easy-way technology. Bringing this to the Marines first means that they will use their considerable intellect and energy to break your machine and send you away with a duffel bag of expensive pieces (so they’re great for finding unimagined points of failure — there is that). Bringing it to them after selling it to the Army is not a panacea. It might be even harder, because they will be energized to demonstrate that the Army did Something Stupid, because if Marines believe three things about the Army it’s that: we have too much money, too little guts, and way too little brains.

You’ll probably need a Marine sniper on board to sell to Marine snipers. Once you do, you won’t get quite the global reach that you do by selling to SAS or its American counterparts. But you get in with the world’s greatest military image machine, and there is that.

You have to be very careful about selling in to Hollywood. (One TrackingPoint precision guided rifle is already in the hands of the most successful firm that supplies movie and TV weapons and armorers). The reason is that an inept display of your product can hurt sales. (It would be very Hollywood to put the TrackingPoint system in the hands of a villain, to be overcome by someone like a Marine sniper or James Bond willing to use superior skill and old school firearms).

What’s Missing From 1st-Gen Tracking Point

While the extant system has undeniable SOF applications, it also has limits, and some technical improvements — none of which are impossible or require TrackingPoint engineers to schedule an invention — would increase its marketability in military precision riflery circles.

Emission Control / Encryption / ECCM

It’s great that you have a computer in a scope, and it’s the wave of the future. But the computer can be located by enemy SIGINT. The video and wifi links need strong encryption, and in addition they need to be controllable so that emissions can be closed down. Even third world enemies often use electronic support measures these days, and so you need some RF low-observability measures, and you also need to have electronic counter countermeasures to ensure usability of the system in an electronic environment.

Two-way communications

This one engenders some risk, but there should be a capability for the opetator to hand off control of the PGM’s optoelectronic systems to someone’s telepresence from a support station. Or even from another field station.

Intelligence gathering MASINT capability

There is everything in this weapons system that’s needed, for instance, to remotely measure a prison camp or a suspected SS-20 missile TEL. This capability would also tie in beautifully with the improved communications and encryption capabilities mentioned above.

A Ballistic Development Interface, SDK or App

Now that we have that in-scope computer, fully integrated with the hardware of the firearm, we need to have a way to make it more adaptable to different ammunition loadings, including one-time, single-mission loads. And that has to be done at the unit level; otherwise you’ve got a potential breach of compartmentation.

This is a sales stopper with top tier units. They develop their own long range capabilities, including, at times, loads, and they do it because they think they, like benchrest shooters, can handload a more consistent, higher-precision round than even premium ammo suppliers can do.

Demonstrated, Documented Durability

The running joke is that a soldier or marine can break a ball from a ball-bearing — just leave him alone in a room with it, and you’re a half hour from looking at a broken ball, and hearing, “Uh, I dunno, sarge. It just broke!” (Bearing-ball, hell, these guys could do that with a wrecking ball). You want your machine to be wrecking-ball strong.

Demonstrated “Fail Safe” mode.

The capability of the system has to degrade gracefully. If you’re sneakin and peekin’ on Day 38 of a “14-day mission,” dead batteries can’t leave you in shoot-randomly mode (let alone, can’t-shoot mode). Even an ACOG, which is probably harder to break than the gun it’s atop, has cast-in backup sights. But with a TrackingPoint gun’s scope being dependent on a CCD display at the shooter end, you can’t afford to have dead batteries.

Full Auto Stabilization Mode

We can’t be the only ones who looked at this and thought, “tag, track & x-act really could up the game of a door gunner and/or Boat Guy.” Hell, those Chenoweth sandrails might come back from the dead, if the gunners in them could actually hit things instead of just contribute morale-raising decibels to a fight. Imagine this Hollywood concoction, except real, and with the boost in hit probability than TrackingPoint promises.

You know you want one (more on the movie gun soon).

Note that these are just for the military employment of tracking point, as combat weapons technology. We haven’t even addressed the utility of tracking point for big game hunting, which is what the thing was developed for in the first place. Its applications for everything from African plains game to heliborne predator control seem self-evident. We haven’t even hinted at the potential for a rimfire TrackingPoint squirrel slaughter system, something that would sell itself once the price comes down.

As we all know, the guys running TrackingPoint are not stupid. They are probably thinking of most if not all of these things already. If not, hey, our rates are reasonable; drop us a line.

New from TrackingPoint

TrackingPoint has refreshed its AR lineup in three calibers (5.56, 7.62, and .300 Win Mag) and also offers three things calculated to increase the appeal of their precision-guided firearms: lower prices, financing, and a virtual reality glass device, the Shotglass.

If you ever wanted to break the last taboo and enjoy a shotglass while shooting, now’s your chance. This one doesn’t hold a precise measure of amber nectar brewed by Scotsmen, though:

The Shotglass can be used to aim and fire the weapon from complete concealment cover. It can record video. It’s most likely use in the real world, though, is as a way for the spotter to direct the sniper on target. We expect we will see more of these used with TrackingPoint’s long-range bolt action rifles than with its ARs, but time will tell. If you buy a TrackingPoint PGF by 30 November 2014, the Shotglass is free; after that, it’s an additional $1k. We’ll probably discuss it in greater depth when TP puts up their Shotglass video; for now, we can’t imagine anyone who wants or has the gun turning the Shotglass down.

The lower prices are relative — they’re still nosebleed-high, just not arterial-nosebleed-high any more. For example, the 5.56 AR is $7,495.

For that, Tracking Point offers:

- Perfect impact on targets out to 0.3 miles, moving as fast as 10 miles per hour.

- The same Tag-and-Shoot™ technology found in fighter jets

- Advanced target tracking technology

- Comprehensive, purpose-built shooting system.

We’ve discussed the TrackingPoint technology before, but the implementation in the ARs differs from that in the bolt guns. First place, you don’t need the guided-firearm voodoo to just shoot. The optic comes up with a crosshair reticle with mil-dots and a red dot at center. Different TP releases have called this “Standard” or “Traditional” mode. Note that the interface does give you range in this mode, but not wind speed or direction.

Next up is “Freefire” mode, which is present, so far as we know, only in the gas guns, not the bolt guns. In this mode, you range something near a group of targets, and the scope adapts to that range and to the atmospherics (note that the wind speed is displayed in this mode). The reticle cues you that the Freefire Mode has been selected, and it eliminates the mildots. Those are not necessary in this mode, because your point of aim is computer adjusted to equal your point of impact. In “Freefire” mode, the Guided Trigger is not activated: the trigger works like any AR trigger.

In Advanced mode, the reticle changes yet again. In this case, it takes several shapes depending on whether and where the Tag has been applied. In advanced mode, the tag is applied with the red button, and then the reticle changes color and shape. The illustration below shows a tag applied to the running coyote. The blue reticle indicates that the shooter is not ready to take the shot: he is not holding the trigger back. When he holds the trigger to the rear, the color changes to red, and the weapon will fire when it is in proper alignment. At any point, the shooter can safe the gun by releasing the trigger.

Advanced mode does something that was considered impossible for centuries: it removes most sources of human error from marksmanship. This is the sort of thing that becomes possible, when you embed a complete Linux computer in a rifle optic, and tie it in to the physical rifle several different ways.

You’ve probably noticed that TrackingPoint expresses distances in decimal tenths of a mile, rather than the yards or meters common in the shooting world, which suggests that they may see their customer base as coming from outside the present limits of the shooting world. (To which we say: welcome! While it’s cool to have a gun that can calculate all this, it’s incredibly empowering to have a head that can calculate all this, and yet, it is possible and available to you. So may your new TrackingPoint firearm be a gateway drug to a new plane of existence for you).

In any event, 0.3 mile is about 480 meters (which the US Army considers the effective range of the individual rifle platform) and 530 yards.

The guns each have a limited effective range which seems like it was programmed into the weapon as a maximum “lock range” (the system has an integrated rangefinder and environmental sensors). This may be intended to ensure that shooters have a positive experience with the precision-guided firearm, but it may also serve to ensure that the ARs don’t cannibalize the higher-end sniper and hunting rifles.

The top of the AR line, the .300 Win Mag monster, offers the same claimed benefits as the 5.56 version, except that it offers “perfect impact on targets out to 0.5 miles, moving as fast as 20 miles per hour,” for a more-than-your-pickup-truck $18,995. (Our pickup, anyway: 4-banger, 2 wheel drive). (Half a mile is 800 meters or 880 yards). Unfortunately, now that somebody’s actually built an AR that’s perfectly sized as a bayonet handle, there’s no bayonet lug.

The 7.62 AR offers slightly less performance (0.5 mi, moving targets to 15 mph) for slightly less money: $14,995. If these prices seem high for ARs, well, they are, but no other ARs do these things, this well.

When TrackingPoint first announced the AR line this spring, there was a .300 Blackout version available. A prototype, using a Daniel Defense upper, was clearly visible in their first AR video, but the gun is not on their price list today. The TrackingPoint technology offers the potential to have a firearm that automatically corrects its zero for the Point of Impact shift common with suppressors; it can also, potentially, store several load profiles. (The ballistics-adapting capability of the weapon depends on it being fired consistently with a load whose performance parameters are known to the software).

The bolt-action rifles, which have not been updated, offer similar performance, actually, in similar calibers. Only the mighty .338 LM extends range to 0.75 miles (1200m — 1320 yards). The bolts are priced differently than their semi-auto kin, a little lower in 7.62 but the highest-price version of the .338 is near-as-dammit $28,000. With great power comes great liabilities, Spider-man. In addition to that, you might want to think hard about budgeting for the extended warranty and the software maintenance contract — software maintenance alone is a stiff $2k/year.

The electricity to drive all this juju comes from batteries in compartments in the stock or the AR and in integral battery compartments in the optics of the bolt guns.

TrackingPoint’s managers are keenly aware that the prices of these guns are an obstacle to sales, and so they have a financing program with decent terms: 10% down, 36 months, 10% interest. (They don’t say how it’s compounded or what the APR is). There’s also a 30-day, no questions asked, money back guarantee, “You can feel completely confident that TrackingPoint stands behind its products.”

We’re not sure it’s really, in their words, “the most incredible shooting system known to mankind.” But we are sure want one of these pretty badly. Just not $18-30k badly. Yet.

For $2k you can spend the day at TrackingPoint in Pflugerville, Texas, meet the staff, see the plant and fire the gun. If nothing else, you’d learn how to pronounce, “Pflugerville,” and maybe even who Pfluger was.

Here’s Another Scope of Tomorrow: Sandia’s RAZAR

Sandia National Labs is better known for playing around with things that go boom and make entire grid squares vanish, than it is for small arms. But the RAZAR scope (Rapid Adaptive Zoom for Assault Rifles) is right in our wheelhouse:

Sandia operates two laboratories for the Department of Energy, but has been known to turn its talents to DOD work.

Sandia says: “RAZAR adaptive zoom is a revolutionary method whereby true optical zoom is accomplished by cooperatively varying the focal lengths of multiple active optical elements in the system.” In effect, this gives you at a minimum the dual magnification of the Elcan SPECTR we’ve used, but without having to take your hand off the rifle. It also offers all intermediate magnifications and fields of view between its extremes. Sandia, again:

RAZAR, and its component lenses, are market leaders from a performance standpoint. It can zoom in milliseconds and perform 10,000 actuations on two AA batteries. The weight, power, and speed requirements for mechanical zoom make them pro- hibitive. RAZAR allows target engagement at diverse ranges and provides several distinct advantages including speed and high resolution at varying distances.

The interface at present is a plus arrow and a minus arrow, fitted on the forearm rail much like a vane switch used with a light. A better interface, if you had a RAZAR with a very wide range of magnification, would be four buttons: plus or minus increment buttons like the current design, plus zoom-to-the-max and -min buttons.

They patented the technology in 2005 (US Patent Nº 6,977,777) and are actively trying to license it to industry. Really trying. Interested?

The RAZAR is actually only one of several Sandia optics developments that are highly interesting. Foveated lenses are another; they developed these to give UAVs a light, compact wide-angle lens but it’s not hard to think of ground forces applications for such a device. And then there are variable radius synthetic mirrors… you can see an overview of these technologies in this promotional PDF from Sandia.

Hat tip: Thanks to John in the comments for getting us started on this.

Tracking Tease

Got a phone call yesterday from a friend at a range in West Virginia. Three guys including a former SF man, a former SEAL (range officer), and a dealer/gunsmith/armorer without military service cracked the box on a new TrackingPoint .300 WM rifle on a long range.

Quick take-aways:

- Best packaged gun any of them had ever seen. In the gunsmith’s experience, that’s out of thousands of new guns.

- Favorably impressed with the quality of the gun and the optic. It “feels” robust.

- It’s premium priced, but with premium quality. Rifle resembles a Surgeon rifle. “The whole thing is top quality all the way, no corners cut, no expense spared.” They throw in an iPad. The scope itself serves its images up as wifi.

- First shot, cold bore, no attempt to zero, 350 meters, IPSC sized metal silhouette: “ding!” They all laughed like maniacs. It does what the ads say.

- Here’s how the zero-zero capability works: they zero at the factory, no $#!+, and use a laser barrel reference system to make automatic, no-man-in-the-loop, corrections. Slick.

- The gun did a much better job of absorbing .300WM recoil than any 300WM any of them have shot. With painful memories of developmental .300WM M24 variants, that was interesting. “Seriously, it’s like shooting my .308.”

- By the day’s end, the least experienced long-range shooter, who’d never fired a round at over 200 meters, was hitting moving silhouettes at 850 yards. In the world of fiction where all snipers take head shots at 2000m with a .308, that’s nothing, but in the world of real lead on target, it’s huge.

- It requires you to unlearn some processes and learn some new ones, particularly with respect to trigger control. But that’s not impossible, or even very hard.

- They didn’t put wind speed into the system, and used Kentucky windage while placing the “tag.” This worked perfectly well.

- An experienced sniper or long range match shooter, once he gets over the muscle memory differences, will get even more out of the TrackingPoint system than a novice, but…

- A novice can be made very effective, very fast, at ranges outside of the engagement norm, with this system.

As Porky Pig says, for now, “Ib-a-dee-ib-a-dee-ib-a-dee-That’s all, folks!” But we’re promised more, soon.

Everybody is really impressed with the Tracking Point system. No TP representative was there and as far as we know this is the first report on a customer gun in the field, not some massaged handpicked gunwriter version. And as far as we know this is the first report on a customer’s experience with both experienced school-trained snipers and an inexperienced long-range shooter. The key take-away is the novice’s ringing of the 850m bell on moving targets. That’s Hollywood results without the special effects budget, and with real lead on real target. No marketing, no bullshit, just hits.

We asked about robustness. This isn’t like the ACOG you can use as a toboggan on an Afghan stairway and hold zero (don’t ask us how we know that one). But it seemed robust to the pretty critical gang shooting it Friday.

We wish Chris Kyle were here to see this. Maybe he already has!

Stand by for more on TrackingPoint, and on more on this range complex when the principals are willing to have some publicity.

Civilian-legal IR laser illuminator

2000-vintage PEQ-2 on an M4 clone. This unit was IR only — note blue lock keeping switch on low power. TNVC image. Click to embiggen.

At the start of the war in Afghanistan, we had the AN/PEQ-2 TPIAL, which is actually something pretty useful under that welter of characters. Let’s break out the descriptive acronym: Target Pointer/Illuminator Aiming Laser. What a TPIAL is, is a laser floodlight and laser sight, slaved to one another so they both align with the weapon’s zero, both working in the infrared regime where it cannot be seen with the naked eye. The PEQ-2 was a decent unit but only worked with night vision, was bulky and took up a lot of your rail, ate batteries like Godzilla carboloading for the Tokyo Marathon, and had a bad tendency to get knocked off zero, or knocked clean out of the fight, if clobbered pretty hard. In time it was replaced by the PEQ-15 ATPIAL. (“A” for “Advanced” Target Pointer/Illuminator Aiming Laser, naturally).

ATPIAL-C on a similar weapon. (This is what PEQ-15 looks like, too). Note size difference between this and PEQ-2 above.

The PEQ-15 has a number of advantages over the PEQ-2. It was smaller, lighter, and more durable. The battery life is even longer (not long enough, but it is an improvement). It has an ingenious “saddlebag” cross-section that lets it mount to the top rail of your carbine without interfering with any ordinary iron or optical sight. Taken together, these things mean it screws up the balance of your carbine less than the PEQ-2 does.

The -15 has a visible as well as an IR laser pointer (selectable), which lets you use the pointer as a day sight if they day isn’t too bright, and lets you use it at night to intimidate enemies or as a pointer for allies without night vision capability. Best of all, it cost less to manufacture, so Uncle Sam could buy and issue more of them, and they became a standard part of a grunt’s kit rapidly.

But there was a problem with these, for the civilian market. The military lasers are Class 3B lasers, and are not remotely eye-safe. (There are lockout switches to prevent military users from inadvertently engaging high-energy mode in noncombat applications). The FDA, which regulates lasers in the USA, does not permit the sale of these devices to members of the public without licenses (which the FDA chooses not to grant).

So L3 Communications, the makers of the PEQ-15, have made a civilian-legal Class 1 version, which they call the ATPIAL-C (“C” for “Commercial”). It’s basically the PEQ-15, made on the same production line out of most of the same parts, just without the high-energy mode. Even side by side they’re hard to tell apart. (Look at the laser safety label — the ATPIAL-C has a triangular warning icon, as befits its lower-energy laser, and the PEQ-2 the red starburst of an eye-unsafe laser). What you give up with the -C model is some range on the laser pointer, a lot of the range on the laser floodlight, ability to focus that light, and 100% of the risk of putting someone’s eye out or having the authorities take your eBay PEQ-15 away because it was originally stolen from Uncle Sam.

The ATPIAL-C is available for pre-order for $1200 from Tactical Night Vision Company (they charge your card when you order; shipping is supposed to be in November). TNVC has an exclusive deal with L3, at lest for the time being, for these things.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.