These two somewhat similar sets of rules were developed by two different leading fighter pilots in World War I. While they apply particularly to the air combat of the area, they are also, to one extent or another, guides to principles of combat and of warfare that are useful to all warriors at all times.

Oswald Boelcke: Dicta Boelcke, 1916.

This was the first real written set of the principles of aerial combat.

- Try to secure advantages before attacking. If possible, keep the sun behind you.

- Always carry through an attack when you have started it.

- Fire only at close range and only when your opponent is properly in your sights.

- Always keep your eyes on your opponent, and never let yourself be deceived by ruses.

- In any form of attack it is necessary to assail your opponent from behind.

- If your opponent dives on you, do not try to avoid his onslaught, but fly to meet it.

- When over the enemy’s lines, never forget your own line of retreat.

- For the squadron: attack on principle in groups of four or six. When the fight breaks up into a series of single combats, take care that several do not go for one opponent.

Mick Mannock: 1917. We’re not sure if Mannock ever named these principles.

- Pilots must dive to attack with zest, and must hold their fire until they get within 100 yards of their target.

- Achieve surprise by approaching from the east.

- Utilize the sun’s glare and clouds to achieve surprise.

- Pilots must keep physically fit by exercise and the moderate use of stimulants.

- Pilots must sight their guns and practice as much as possible, as targets are normally fleeting

- Pilots must practice spotting machines in the air and recognizing them a long range, and every aeroplane is to be treated as an enemy until it is certain it is not.

- Pilots must learn where the enemy’s blind spots are.

- Scouts must be attacked from above and two-seaters from beneath their tails.

- Pilots must practice quick turns, as this maneuver is more used than any other in a fight.

- Pilots must practice judging distances in the air as these are very deceptive.

- Decoys must be guarded against – a single enemy is often a decoy – therefore the air above should be searched before attacking.

- If the day is sunny, machines should be turned with as little bank as possible, otherwise the sun glistening on the wings will give away their presence at a long-range.

- Pilots must keep turning in a dog fight and never fly straight except when firing.

- Pilots must never, under any circumstances, dive away from an enemy, as he gives his opponent a non-deflection shot – bullets are faster than aeroplanes.

- Pilots must keep an eye on their watches during patrols, and on the direction and strength of the wind.

In retrospect, Boelcke’s shorter, simpler set of rules are more nearly universally applicable; many of Mannock’s applied only to the particular circumstances of the Western Front and the evenly balanced aircraft there; to commit to a turning fight and not dive away would have been doom for most Allied pilots facing the Japanese in the next war, for instance. Today, squadron bars and ready rooms are more likely to display a framed copy of the Dicta Boelcke.

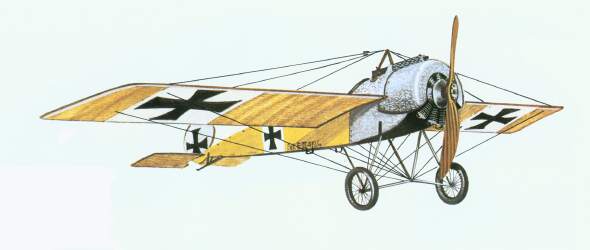

Of course, Boelcke’s era was two to three years before Mannock’s, an eternity in wartime. Boelcke was the pilot who first tested the Fokker machine-gun synchronizer that allowed the Fokker E. III to fire forward through the propeller, in 1915; he was a contemporary of Max Immelmann in the earliest days of air combat, and flew the early Fokker monoplanes and later Pfalz and Albatros D. II biplanes. He was so well regarded by all sides that he would receive a decoration from his French enemies (for saving a drowning child).

Mannock flew the Nieuport but is primarily associeted with the S.E. 5a, a biplane with an engine of 160 to 200 horsepower, numbers unheard of in Boelcke’s day, and two forward-firing guns. An Irishman whose estranged father was a British Army NCO, Mannock hoped Home Rule for Ireland would be one result of the war. As a civilian, had been a captive of Germany’s ally Turkey and been abominably treated, and he seethed with hatred for the enemy and was contemptuous of chivalry and compassion. To his subordinates (he ended his war leading a squadron), he was a committed teacher and the sort of a leader who would put a squirt in an enemy plane and let the wingman finish it; where the early aces Boelcke and Immelmann competed to see who could score more kills, Mannock’s final score, all histories agree, can’t be known with any certainty, only that it was higher than his claims.

Neither ace would survive the war. Boelcke perished after a midair collision with a wingman, Erwin Böhme, in October, 1916 (his other wingman that morning was a relative newbie named Manfred von Richthofen; Böhme and Richthofen both became great aces in their own rights); British airmen in a POW camp sent a card to his funeral. Mannock, after handing a shared kill to a young wingman he was instructing, led the formation over a machine-gun post and both planes were shot down. The wingman managed an emergency landing in friendly lines, but Mannock went down in flames. A few months later, the war ended, but Mannock’s bleak prediction to a friend had come true: “For me, there is no ‘after the war’,” he reportedly said.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

3 thoughts on “Two sets of fighter rules”

The first real term paper I ever had to write was on WWI aviation. Mid 70s, have had a moderate interest ever since.

You mentioned several weeks ago a post on WWII gliders. I don’t think I missed it…

Nope, not finished. An interesting technology that had a lifespan of just one war.

Ever seen the short film “The German?” It fits right in with this post, I think you would like it.

https://vimeo.com/31202906