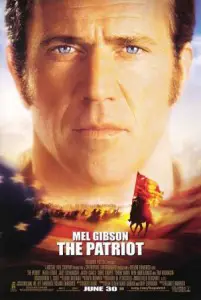

The American Revolution is an interesting conflict from both the general historical and unconventional warfare aspects, but it’s been little celebrated on screen of late. The Patriot from 2000 was a successful blockbuster starring Mel Gibson and directed by Roland Emmerich. Along with a strong script and clear heroes and villains, the movie was hustled along by strong performances by supporting actors including Jeremy Isaacs, Adam Baldwin, and a young Heath Ledger.

The American Revolution is an interesting conflict from both the general historical and unconventional warfare aspects, but it’s been little celebrated on screen of late. The Patriot from 2000 was a successful blockbuster starring Mel Gibson and directed by Roland Emmerich. Along with a strong script and clear heroes and villains, the movie was hustled along by strong performances by supporting actors including Jeremy Isaacs, Adam Baldwin, and a young Heath Ledger.

The movie is set in South Carolina. Ben Martin (Gibson) distnguished himself during the French and Indian War, but he’s reluctant to fight this time around. Of course, in the end he does, or there’d be no movie. The villain, Colonel William Tavington (Isaacs), is loosely based on British officer Banastre Tarleton — not on the historical Tarleton, exactly, but the American legend of “Bloody Ban,” a considerably worse character than the flesh-and-blood Tarleton was; and Isaacs’s cold, merciless Tavington takes the monster of legend and raises him to Godzilla proportions.

Gibson’s character is loosely based on Francis Marion with a leavening of several other historical southern militia leaders, and an overlay of Hollywood.

Historical Accuracy

We’ve already mentioned the characters’ departures from their historical prototypes. Tavington is particularly over-the-top, at one time rounding up civilians into a church and them torching the church. There’s no record of such an atrocity in the Revolutionary War; instead, the screenwriter seems to have adapted the 1944 Nazi enormity at Ouradour-sur-Glane in France to his screenplay. Tarleton’s descendants and Britons, particularly the residents of Tarleton’s native Lancashire where he’s still fondly remembered, were livid. Now, Tarleton (and his American opponents for that matter) was not interested in fighting by Marquess of Quensberry rules and the real South Carolina campaign saw abominable acts by both sides, acts which were more tolerated in their day than they would be now. But the movie makes no pretense of being a documentary; it’s a popcorn flick, take it as offered.

The skirmishes and battles in the movie are not identified by name, and re either fictional or combine events and actions from multiple real battles.Again, it’s a fictional movie set in a real time period.

The skirmishes and battles in the movie are not identified by name, and re either fictional or combine events and actions from multiple real battles.Again, it’s a fictional movie set in a real time period.

There is a bit of depiction of the irregular nature of the war, in that the fluidity and patrols-and-ambushes nature of the war in the South spends some time on screen, but there are also massive setpiece battles that, frankly, didn’t take place until the very end of the war at Yorktown. In the Revolutionary War, South Carolina was an ancillary theater of war, so while the fighting was desperate enough for those engaged, its primary bearing on the outcome of the war was the logistical burden that the Carolina guerillas placed upon the British forces, tying down significant numbers of Redcoats and Loyalist militia to secure key points and lines of communications.

The real Tarleton earned much of his reputation as a bold cavalry leader and a leader of those Loyalist militiamen, and once chased the historical Francis Marion all day until Marion evaded him in a swamp, which caused Tarleton to call him “that d—ed Swamp Fox,” a name which stuck to the Colonial. That scene did not make it into the Patriot.

One thing you always see in irregular war is divided loyalties, and quislings or loyalists (depending on your point of view). (One of the reason the British indie film It Happened Here (1965), a previous Saturday Matinee, is so brilliant is that it shows you resistance from the collaborationist point of view). In The Patriot, the character played by Adam Baldwin is a fellow member of the colonial legislature, who winds up taking the King’s Commission and fighting for King George III alongside Tavington. His disposition is unclear at film’s end, but it’s interesting to note that the real-world Marion used his fame to advocate for amnesty for loyalists — an unpopular idea at the time. Whole regions of Canada would be settled by Loyalists expelled from the new United States, and expropriated of everything but the shirts on their backs.

Gun Accuracy

Charleville musket… the distinct oval opening in the hammer is a characteristic of French design. Click to expand.

Back when Hollywood made more movies about the Revolution, they took much less care with the weaponry. The crew here worked hard to put plausible arms in the hands of their actors and extras, and it shows. The British are armed and accoutered properly for the period (although we seem to recall that the real Tarleton’s men were the ancestors of the later Green Jackets, and so shouldn’t have been in red coats, except to spare audiences confusion). The British carry Brown Bess muskets’ the Colonials, French Charlevilles, both generally correct. Earlier in the war, and in the North, militia weapons resembled the Brown Bess, or were Besses. But by the time of the events shown here, Louis XVI’s France had become the most significant armorer to the Continental Army. When the US made its first standard infantry muskets, they would owe more to the Charleville than the Brown Bess.

When Ben Martin and his sons go out to settle scores, they do it with flintlock rifles of the Kentucky or Pennsylvania style. This is defensible, even plausible. While smoothbore muskets were the rule for infantry combat in the late 18th Century, private citizens prized more accurate rifles for hunting.

In the battle scenes, there’s never enough smoke, and some explosions tend to be rather too firey — both quite typical of Hollywood. The power of the British line (although not the power of the square) is depicted well, as is the corrosive effect on morale that leads from any breakdown in the element to a deep spiral plummet into chaos.

We’re not sure about the accuracy of the cannons. However, in one scene, the British and Continental forces are mixed in a melee and the cannons have ceased firing because the gunners cannot discriminate friend from foe. At that point, the British general, Lord Cornwallis orders the gunners to fire into the scrum without regard for friendly casualties, and the gunners do. This is often taken by modern audiences to be a Hollywood stunt, like the church-burning; but this was actually a recognized, if cold-blooded, tactic at the time, and Cornwallis himself did use it at Guilford Court House, one of the battles that provided concepts for this movie. In fact, it broke the American line and led to a British victory, albeit a sanguinary one.

Bottom Line

The Patriot is a fun and intellectually non-taxing action movie set in a backwater theater of the Revolutionary War. It attracted a great deal of criticism at the time, although movie critics gave it generally positive reviews, and as is pretty normal for war movies of any kind, audiences liked it much more than the hemp-scented herd of hippies that movie critics apparently are. (Compare, say, Metacritic or Rottentomatoes critics scores with reported audience ratings). If you’ve ever loaded and fired a flintlock musket, you’ve seen how complicated and fiddly it is. You can’t help but admire the soldiers who were able to conduct that complicated drill under fire (and even under your own side’s grape shot, if you were unlucky enough to work for Cornwallis). These old guns are great fun to watch on the screen, too… you have to keep telling yourself that they weren’t old at the time. A flintlock Kentucky rifle was the high-tech of the 1780s.

It’s available at all the usual places, including Amazon in the theatrical cut and in an extended (10 minutes) version that restores some scenes that were cut for time, mostly character-establishing scenes. (Links are to DVD, but you can find blu-ray at links also. One note, despite the verbiage about the ten-minute extension, both DVDs list a 165-minute run time).

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.