If you have a well-rounded firearms education, the name Benelli needs no introduction. Now part of the Beretta family, the marque has been known for its semi-auto shotguns since its founding in 1967. But Benelli made an attempt, in the 70s and 80s, to make a NATO service pistol. It’s interesting for its unusual toggle-lock mechanism (one we missed when we covered toggle-locking), its fine Italian styling, and its relative rarity: internet forum participants, at least, think only about 10,000 were made. (We do some analysis on this claim below, and posit a lower number).

There were other Italian semi-autos at about the same time, like the Bernardelli P-018, competing in part for European police contracts, as many Continental police departments replaced 7.65mm service pistols during the 1970s and 80s rise of European communist terrorist groups like the Red Brigades and Baader-Meinhof Gang. But the Benelli was a unique blend of design and functionality. Arriving too late into a market saturated with double-stack double-action pistols, it might have been a killer competitor for the P1/P.38 or the Beretta M1951 twenty years earlier, but by the end of the eighties, the market was heavily oriented towards double-stack, double-action, and often, ambidextrous-control service pistols. Even European police services who had thought 8 rounds of 9mm a real fistful of firepower had moved on — and so did Benelli, retreating to a concentration on its market-leading shotguns.

Mechanics of the B76

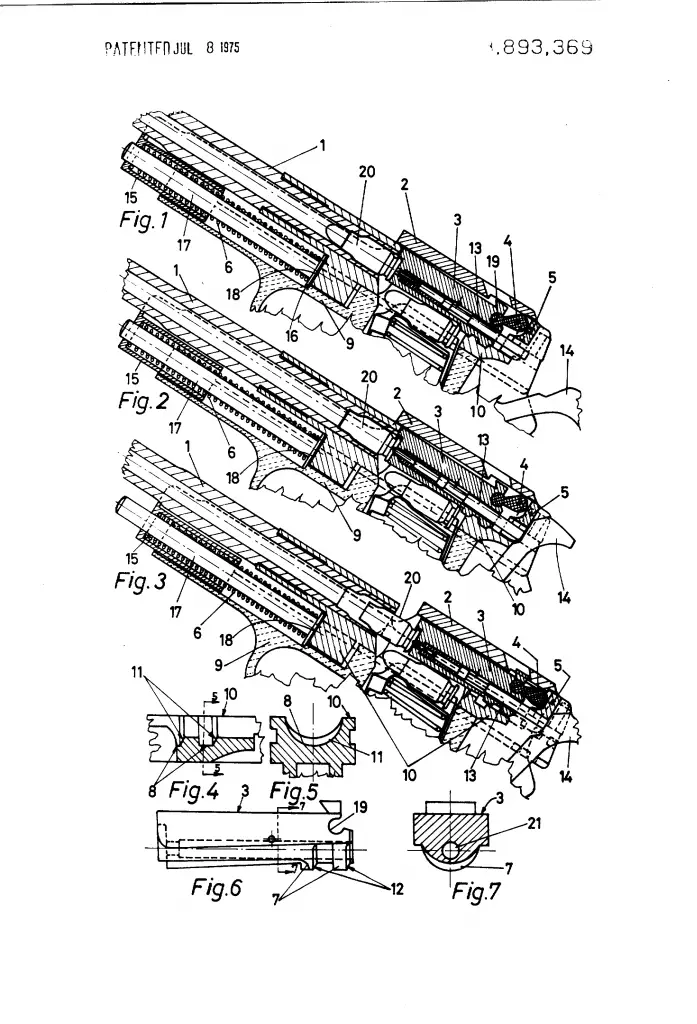

The toggle-lock is not truly a lock in the sense of a Maxim or Luger lock, but more of a hesitation lock or delayed blowback. Other weapons have used a lever in delayed blowback, like the Kiraly submachine guns and the French FAMAS Clarión, but the Benelli one is unique. It’s described in US patent No. 3,893,369. The toggle lock or lever is #5 in the illustration below, from the patent.

Benelli often cited the fixed barrel of its design as a contributor to superior accuracy in comparison to the generic Browning-type action.

Aesthetics & Ergonomics

The styling of the B76 is a little like its Italian contemporary, the Lamborghini Countach: angular, striking, and polarizing. You love it or hate it, or like Catullus, both at once: Idi et amo. It came in a colorful printed box, resembling consumer products of the era…

…or in a more traditional wooden case.

The somewhat blocky slide needs to be protected by a holster with a full nose cap, if you intend to carry the B76. It’s a large pistol and it would be prone to print if you did, much like any other service pistol like the M9, the Glock 17, or various SIGs. Where the pistol comes into its own is when you handle and shoot it. The safety falls right to hand, like that of a 1911, although as a DA/SA gun it’s perfectly safe to carry hammer down on a loaded chamber. The grip angle is much like the P.08 Luger, making for a very natural pistol pointing experience. The pistol’s steel construction and roughly 1kg (2.2 lb) weight makes it comfortable and controllable to shoot. The heavily-contoured grip on the target models makes it even more so.

The guns are known for reliability and accuracy, and their small following is very enthusiastic, reminding us of the fans of the old Swiss SIG P210 pistol: the sort of machinery snobs whose garage is more accustomed to housing premium European nameplates than generic American or Japanese iron, and who not only buy premium instead of Lowe’s tools, but who can take you through their toolboxes explaining why the premium stuff is better.

Production and Variations

The Benelli company was relatively new when it designed the B76. The US Patent application for its locking mechanism dates to 1973, and the planned start of production was 1976 (that may have slipped).

There were several variants of the B76, most of them sold only in non-US markets. The B76 was the name ship of the class, if you will, but there were several variants. The B77 was a scaled-down model in .7.65 x 17SR (7.65 Browning/.32 ACP); it was a completely different gun. The B80 was a 7.65 x 22 (7.65 Parabellum/.30 Luger) variant, largely for the Italian market; only the barrel and magazine differed from the B76. The B82 was a variant in the short-lived European police caliber, 9 x 18 Ultra (sometimes reported, mistakenly, as 9×18 Makarov). In addition, there were several target pistol variants, including the B76 “Sport” with target sights, grip, longer barrel, and weights, and a similar target pistol in, of all things, .32 S&W Long called the MP3S. We’ve covered some of these exotic Benellis before, in the mistaken belief that we had brought this post live, which we hadn’t. (D’oh!)

The one modification that might have brought Benelli sales to police departments or military forces was never done, and that is to develop a double-stack magazine. A “mere” 8 rounds of 9mm was already insufficient in 1976, when many NATO armies already issued the 13-round Browning Hi-Power as their baseline auto pistol, and the novel Glock 17 coming on strong.

Benelli dropped the pistols from its catalog in 1990. The company still produces its signature shotguns and a line of high-end target pistols, and even some rifles based on the shotgun design, but its foray into the pistol market has left Benelli with bad memories, red ink and a few curiosities in the company museum. But the curious pistol buyer looking for a firearm with a difference will find here a remarkable and character-rich handgun. If you’re the sort of man who can rock an Armani suit or avoid looking ridiculous in a Countach, this might be a good companion piece.

We’ve mentioned the internet claims of production of 10,000. The highest serial number we found on the net (5462) was well below that, but we certainly don’t have a statistical grasp on production yet. With 7 known serial numbers we can make a rough calculation that there’s a 9 in 10 probability the total production is under 6400, and a 99% probability it’s under 8500. That’s assuming our rusty MBA-fu still retains its potency.

Market

No B76s are on GunBroker at this writing, and only very few — single digit quantities — have moved since 2012. The guns offered were all in very good to new-in-box condition, and they cleared the market at prices from $585 to $650. One went unsold at $565 against a reserve of $600, hinting that, despite these guns’ character and quality, there’s just not much of a market for single-stack full-size DA/SA autopistols.

For More Information

We’re seeking a better copy, but for the moment, heres a .pdf of the manual. Unfortunately, it takes greater pains to describe the mundane DA/SA trigger system than the rare, patented breech lock!

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

10 thoughts on “Toggle-Locked Orphan: the Benelli B76”

.32 S&W is a not uncommon traget shooting calibre in Europe. I have a Walther GSP in .22 and there is an alternative barrel and magazine in .32 S&W that can be simply swapped out for shooting in the larger calibre competitions, since this is the smallest calibre allowed for the centrefire competitons (unless they have changed it). The Walther GSP was the standard pistol for competitions in my area for many years.

Also Italy had strange specific weapons laws that did not allow weapons in military calibres to be sold on the civilian market. I remember that 9×19 was forbidden earlier. I think that has changed, but I don’t live there so I don’t really want to say anything definite.

Simon

Yes, that is why 7.65 was so popular in Italy, a 9mm ban. Dunno if it still stands. (Mexican law similarly bans military-caliber cartridges for civilians, not that it has an impact on the criminal DTOs).

The .22 GSP was popular here with the bullseye crowd, the .32 version is rare but it shows up now and again. Not many shooters are interested in serious competition, and for them, European guns are very popular, Hammerli and Walther. The OSP which is, IIRC, the .22 short version, is more common than the .22LR I think, just due to a lack of .22 short autoloaders for rapid fire. Hammerli makes a nice one, too. Very hard to move if you’re a dealer, though. It’s just a minority interest among American shooters.

Like most things Italian: Beautifully designed, tangential to real utility and hopelessly distant…..but I want it.

Badly.

I dont suppose you could put a link to the old articles? It might be nice to read those one after reading this one.

Here are some links to B76 articles that were published in American Handgunner during the early 1980s

If I’m parsing the patent drawings correctly, that’s not a hesitation locked weapon.

In hesitation locking, e.g. Remington 51 and some obscure Swiss SMGs, the bolt snaps into place when the moving parts group goes into battery, but there’s a small gap between the mating surfaces of the bolt and the receiver. The bolt gets shoved back across this small gap (hopefully too short to cause a case head failure), and comes to rest. The bolt carrier is accelerated, and a short time later unlocks the bolt and cycles, much like a gas-operated weapon.

I’m not seeing any gap at all between the bolt and the locking lugs in the rear of the frame in that picture. The lockup looks completely stationary.

Which brings up the question of how on earth the slide gets accelerated to unlock and cycle the action. I think that it’s actually inertia operated. The recoil of the frame in the shooter’s hands accelerates the slide, which unlocks the bolt via the little toggle/link thingie. Or perhaps by those inclined cam surfaces. Why on earth does it have both a link and inclined cam surfaces?

My impression from examining one some years ago (I don’t have one currently) is that it is unlocked by the action of the lever/link (#5 in the drawing).

I just read the patent, and you’re right.

The bolt locks by tilting the rear against those locking surfaces (ala FAL or SVT). At the moment of firing, the recoil accelerates both the slide and the frame, but since the frame is being held, it begins to decelerate. The slide continues moving, and since that link offers a substantial mechanical advantage, it unlocks the bolt very quickly; so quickly that the residual blowback pressure is still present in the bore, and that provides the rest of the energy to cycle the BCG.

So it’s an inertia-unlocked delayed blowback design. Weird.

I still have absolutely no idea what those cam surfaces do.

Armani is overly pedestrian.

I prefer A. Caraceni and occasionally Gieves & Hawkes 🙂

I was told by a British counterpart that I shouldn’t fight middle age weight gain, he would recommend me to his tailor. He was one of those gentlemen who doesn’t know (or want to) what he pays for a suit. He did look splendid for an old, stout guy.