As a kid in the sixties, you couldn’t get away from ’em. Turn on Combat with Vic Morrow, and there’d be one in every few episodes, hauling American infantry up to the point where they’d start walking. A couple years later, The Rat Patrol stuck German Balkankreuz symbols on them and made ’em the bad guys. Around that time, they made the TV news, too, carrying long columns of hard Israeli troops to victory over Egyptians, Jordanians and Syrians with more modern weapons. Our cousin’s friend Charlie even owned one and drove it on parades — and to winch State Troopers out of snowbanks in blizzards. The White M3 half-track troop carrier, and its variations, were everywhere. It, and its foreign competitors, had considerable mindshare and were intensively developed from about 1930 through 1945, but none were made after war’s end. By the time the Israelis stormed Jerusalem, the armies that developed the halftracks and used them in WWII were all out of them — they’d surplused them, and when there were no surplus takers, towed them onto gunnery ranges, where the bones of a few remain.

Why did half-tracks go from invention, to ubiquity, to obsolescence in 15 years? Why did they hang on another 20 in places like Israel? These are interesting questions, and the answers begin in World War I.

World War I Prime Movers’ Limitations

While everyone thinks of World War II as the first mechanized war, the forces of all nations saw the potential of internal-combustion motive power early, and they all built thousands and thousands of prime movers. (Germany, Britain and the US were experimenting with artillery tractors even in the 19th Century). None of these was quite like the ones that would be used in the next war. There were several ways to put power to the ground, and by 1918 several competitive ways were in use. These included:

- Full-tracked vehicles like the US Holt (later Caterpillar) tractor;

- Steel-tired wheeled vehicles

- rubber-tired wheeled vehicles. In 1918 this often meant solid rubber tires.

Each of these vehicles came with its own set of pros and cons. Grossly simplified:

- Full-tracked vehicles had superior off-road and broken-field mobility, important in the morass of the Western Front. But they were slow, had high fuel consumption per unit of work, were prone to breakdown and demanding of high maintenance (even more than other 1918 machines), and the metal tracks interacted harshly with prepared (especially macadam) roads. The complexity of the steering arrangements was a key factor in shortening tracked prime-mover life.

- Steel tires had fair mobility (expecially given all-wheel-drive, a new development) but had some of the same problems with roads.

- Rubber-tired vehicles had the worst traction of the bunch, especially given the early 20th Century’s skinny (and often solid) tires.

Every army that employed powered prime movers, which certainly included the British, German, French and US, knew two things by Armistice Day: motorized prime movers sure beat horses or laying railroad track, and they wanted a vehicle that combined the cross-country mobility of the Holt tractor with the lower maintenance of conventional tracks.

The half-track idea was simple and logical: use the tracks for power, and wheels for steering. In fact, before Holt worked out differential steering, the earliest Holt tractors had a single wheelbarrow-like “tiller wheel” out in front. Semi-tracked steam tractors had existed even earlier, but the internal combustion engine made it possible to make one light and efficient enough for military purposes.

A French engineer named Leon Kégresse took the idea and ran with it. He was working for Tsar Nicholas II of Russia, and so the first halftracks were Russian vehicles; he developed a kit that could be fit to touring cars, adding a suspension with small road wheels and return rollers, and a large driving wheel and idler wheel, driving a continuous rubber track with or without metal grousers. The contraption was steered by front wheels, or, given Russian winters, skis. After the Revolution, Lenin used such a vehicle, but Kégresse left Russia. The Putilov factory, which built Austins under license, made an armored vehicle based on an Austin truck chassis with Kégresse running gear and home-grown armored skin. These saw combat in the Civil War and in the Soviet-Polish war.

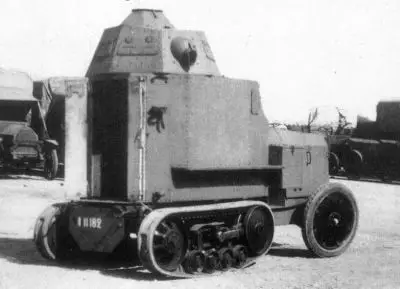

Putilov Kégresse knocked out and captured by the Polish forces. It is named “Ukrainets” (“Ukrainian”) and bears the slogan “All Power to the Soviets!” It looks like the Poles read the label and delivered plenty of power to the thinly-armored machine.

Information and the image of the Polish-zapped Putilov is from this Polish link and this one (which have a ton of data on these rare combat vehicles) via Axis History Forum.

Interwar Development of Halftracks

The three biggest halftrack developers were France, the USA, and Germany, and each took a slightly different approach. The Soviet Union, on the other hand, backed away from its early enthusiasm for halftracks.

France developed and showed off several generations of Citroën halftrack, based on Kégresse’s improvements to his own design. Like all things Citroën, it was somewhat weird and woolly in its industrial design — it worked, but it wasn’t like anything the other powers put together. The vehicles were used in some celebrated explorations, like in Africa and in this ill-fated one in Canada, now represented by a beautifully restored halftrack:

France was one of the earliest adopters of the halftrack, with a Citroën model being standardized in 1923 and other Citroën and Panhard models following.

The M23 Citroën with its Kégresse drivetrain. FMI see the chars-français web site (French language).

The interwar French Army lagged its peers in mechanized-force development, and they never standardized an armored troop-carrier version of the Citroën. The armored versions, like this one, were more like half-tracked armored cars; they were discontinued a few years before the war. La Belle France had the Maginot Line, so why worry?

The USA licensed Kégresse’s patents and designs and from about 1930 worked through many iterations before arriving at the familiar White halftrack. It was a lightly armored box with pretty standard American truck running gear, except for the Kégresse-derived tracks and suspension.

![Original caption: Treads for Army halftracks, fresh from the curing press of a large Ohio tire plant [BF Goodrich, Akron OH]. Grooves are buffed on the ends of the track section." Office of War Information official photo by Alfred Palmer.](/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/m3-halftrack-tracks-775x1024.jpg)

Original caption: Treads for Army halftracks, fresh from the curing press of a large Ohio tire plant [BF Goodrich, Akron OH]. Grooves are buffed on the ends of the track section.” Office of War Information official photo by Alfred Palmer.

Almost 50,000 of these vehicles were made in many variants, and they were delivered to many US allies, including France and the USSR during the war, and many smaller nations postwar. The most common versions were troop carriers — with a single small door in back and no overhead cover, the M2 and M3 halftracks — and self-propelled light anti-aircraft vehicles, especially the quad .50 version, the M16 halftrack.

The Germans were initially determined to pursue versatility.

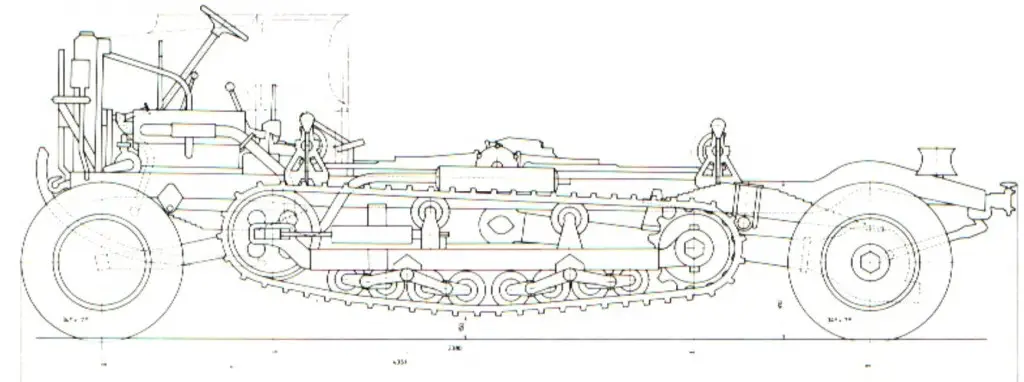

They made vehicles which could convert from wheeled to half-tracked; Krupp, Dürkopp and Horch all made experimental vehicles. These included machines that could operate on road or standard-gauge railways, and also machines that could run on wheels but then lower tracks like an airplane’s landing gear, and then raise them to revert to wheel drive. The Reichswehr term for it was “R/K Schlepper” for Rader/Ketten Schlepper,” in English, Wheel/Track Transporter.

This is the Maffei K/R Schlepper design. Note the similarity of the trackes to the Kégresse design. From Spielberger, p. 56.

Maffei made one about the size of a US WWII 3/4 ton truck or weapons carrier, that achieved series production. Except, this was series production at Reichswehr production totals: 24 vehicles. Here are pictures of the Maffei MSZ 201 in street (wheeled) and off-road (half-tracked) modes. The tracks stowed above the rear wheel wells.

By 1933 the Germans were done fooling around with these modified Kégresse designs, and had developed an interleaving suspension that would be used on all their combat and support halftracks, as well as on some of their best tanks.

1933 interleaved design prototype.

In the end, the Reichswehr and later the Wehrmacht developed a wide range of vehicles based on this principle, from ultra-light halftrack motorcycles to massive tractors, and a parallel line of armored combat halftracks. While the US standardized on one chassis, the Germans built several different size-optimized chassis.

The Soviet Union, undergoing a cataclysmic process of forced industrialization with an emphasis on heavy and military industry, also developed prime movers, but they went for full-tracked or fully-wheeled vehicles. They experimented with halftracks — after all, it was originally a Russian thing — but they didn’t find them as reliable as their robust tractors based on tank running gear. During the war, they’d receive and use thousands of Whites via Lend-Lease, but they never saw any of the Lend-Lease weapons as anything but a wartime stopgap.

The End of the Halftrack

The US and Russia developed high-speed, reliable artillery tractors from a basis of tank automotive components. These full-track vehicles had superior off-road mobility to halftracks. With proven components in the parts bin, designers no longer feared differential steering and halftracks would be all over as military vehicles.

Surplus ones fought on. Indeed, the Israelis still have some on hand. But when the Jewish state developed its own infantry fighting vehicle, they went with a full-tracked configuration.

The half-track may not be entirely dead, but it seems to be pining for the fjords. The concept of tracked propulsion and forward steering faded from military inventories, but it did get a new lease on life — in the snow, thanks to Canadian manufacturer Bombardier. But that’s another story.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

17 thoughts on “The Rise and Fall of the Halftrack”

I thought that I remember reading somewhere that the construction of the halftrack allowed the Germans to circumvent some of the restrictions of the Versailles Treaty. I think they were used extensively in towing artillery.

Combat!, layered upon my father (WWII USMC Corporal), his contemporaries, my uncles, (Bulge, Remagen, Italy and Pacific), and a Type 99 Arisaka from my uncle who “took it from the jap who tried to kill me” was formative motivation for my own enlistment.

Well, as a half-assed student of military history, the half-track has always seemed to me a half-assed answer to a question which had only been half-asked. (See what I did there?)

Seriously, as a former light infantryman, the half-track just seems to combine all the disadvantages of fully-armored, fully-tracked vehicles, with all the vulnerabilities of unarmored light vehicles. I.e., it’s as big and attention-getting as a tank or IFV, but with little or none of the associated firepower, mobility, and armor protection.

I also understand that now is not the 1930s, and military technology has changed, but, I still don’t understand the rationale of half-assing it. I mean, if you’re going to go with a tracked, armored vehicle, why not go all the way?

Your mileage may vary, I guess, but I just don’t get it.

Building steering gear for a full-tracked system is not trivial; you can get by with a half-track using front wheels for steering plus a little braking, and a bunch of slop in the transmission. Plus that, you simplify the multi-axle wheeled design to a couple of differentials instead of 3 or 4.

Half-tracks serve a purpose, on the trip from primitive motor development to the more complex. If your factories are over-taxed, after the apocalypse, they may come back.

Because they were cheap! Not just in initial cost but in training costs, POL requirements, service / repair costs and manning requirements. Also, although I bet they didn’t broadcast this to the troops in them, or the folks back home, they are cheaper to lose. If you’re fighting a World War cheap is good. If you can get it good enough to work, but really cheap, you can gift bunches of them to expendable surrogates (AKA Allies) and they can motor up to the FEBA and get killed instead of us. Cheap is often misunderstood and underrated.

To be fair, the French dumped their halftracks because they had recognised the drawbacks and were in the process of replacing them in the various roles with new wheeled and full-tracked designs. They just didn’t quite finish, and misused what they had when the war started. Zaloga’s Osprey books French Tanks of World War Two (1) Infantry and Battle Tanks and French Tanks of World War Two (2) Cavalry Tanks and AFVs are informative reads on a topic I’ve never seen a lot on in English language press.

Similarly I have, but have yet to read, the Osprey books on armored vehicles of both the Whites and Reds in the Russian Civil War, which has a fair amount on halftracks, and a book on an even rarer beast, the armored train.

Something that has always fascinated me is the Citroen-Haardt (sp?) Trans-Asiatic expedition of circa 1934 or so. As I recall from some very old National Geographics they crossed the Pamirs. The “roads” were basically goat trails in some spots. At places they not only had to do some plain and fancy road-building, but had to partially disassemble the half-tracks to boot.

I recall seeing the documentary about the “champagne safari” from Edmonton westward. I was thinking that they hever made it across the Canadian Rockies, although the volunteer in your video, who should know, says that it fell apart in BC. The terrain: swamps, forest, mountains, and lots of the Canadian strategic rock stockpile, was beyond rough.

Exploration is serious business. The Eminent Victorians who made it look like a dilettante’s hobby were not actually dilettantes, they were amateurs in the truest sense of the word — people who excel at something for the sheer love of it.

As noted, the IDF continued using half-tracks for a loooooong time. Simply put, they were cheap and already there. They are pretty rugged, too. Doctrine also played a part, since they were mostly considered a battle taxi for the infantry who should be outside on their feet when the fighting happens. You can see half-tracks still in use in 1973, in the Yom Kippur war. After a few days, as doctrine changed on-the-fly to ‘the infantry needs to be right with the tanks (or even moving ahead) to provide solutions for the Egyptian AT effectiveness’, those old half-tracks were pulling duty they no longer were suited for. There were M113s also, but not enough to go around and, of course, they burn like a box of matches.

By my draft in Aug. ’80 we (the light infantry) had all M113s available. More mobile and agile. Imagine my surprise when I discovered some old half-tracks STILL in use in some units for things like the battalion medical team. When I went to the medic’s course, all our combat equipment for the course was old, including – yep- half-tracks for mobile practice. Then again, we still practiced air evac and initial jumps on old Dakotas.

_The Lions Gate_ by Pressfield made me never want to get in one of them – lightly armored, gasoline powered, full of troops = bad combo.

At least they didn’t burn as hot and fast as an unmodified M113. I was so dismayed in basic training when I learned we’d have to ride in one of those things! And I was so relieved when I later arrived at a foot mobile/jeep mounted recon company. We had a few M113s, but I never set foot in one.

Mind you, do you have any idea how naked and vulnerable you can feel (If you foolishly waste time thinking about it) in a jeep on a field full of growling tanks? The illusion/delusion of being inside the personnel carrier can be comforting, in a way.

Good point. Being stuffed into a metal box that burns like crazy doesn’t inspire confidence.

I was periodically stuffed into Amtracs as a kid. Watching them roll off the front of the ramp at full speed and make that plunge, I just could never figure out how they float. I’m convinced the squids left the vents open a crack so some water would spray in.

Easy to build and maintain and best of all, easy to train drivers since it steered like a regular car or truck.

My Dad spoke of being familiarized to driving one during WW2 he said once you got it going everything was like a truck, but shifting involved mashing the gas, double clutching and placing the foot upon the dash just to change gear.

Any soldier draftee who could drive a car or truck could drive a half track.

I was a squad leader on an M16 while doing occupation duty in S. Korea, 1954/1955.

A drawback as ack-ack was that the turret couldn’t move fast enough to track a crossing airplane if it were above 200 mph. Coming in directly? Big mistake.

Guys who had seen combat said that they were great against human-wave assaults, but it was shoot-and-scoot because the Chinese were really, really good with their little mortars.

Training was for two guns at a time, and the old “Fire a burst of six.”

The concept is not entirely dead

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2vNF8tGZCq0

Kegresse lives! As I’m sure you know, you can track-up many commercial vehicles off the shelf today-

https://www.mattracks.com/#

http://www.americantracktruck.com/

It ought to be possible to half-track them too, maybe with portal axles in front or big wheels.