From the very beginning of M16 production, according to the preponderance of records, the Army version was the M-1 A1 with the forward assist. But the MIL-STD that included the nascent M16 for the first time, MIL-STD 635B: Military Standard, Weapons, Shoulder (Rifles, Carbines, Shotguns and Submachine Guns), covered only the M16 version.

MIL-STD-635B was published on 7 Oct 1963. The weapon was, in this instance, the only exemplar of a new category of standard:

5.1 Detail Data for Standard Items (Standard for design and procurement)

5.1.1 Rifles

5.1.1.2 Caliber .223.

The two entries in Standard 5.1.1.2 are:

(a) RIFLE, 5.56-MM M16, FSN 1005-856-6885; and

(b) RIFLE, 5.56-MM: M16, w/e, FSN 1005-994-9136.

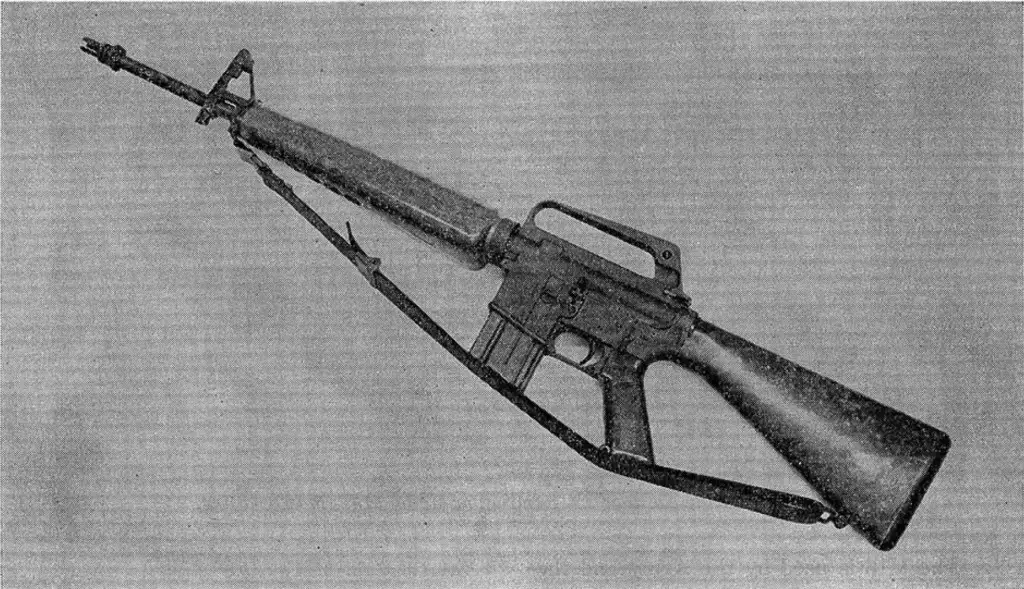

And the published illustration, seen above, although grainy (and distorted by the moiré patterns that result from scanning half-tone images) in the copy we examined (from, once again, the Small Arms of the World archives, for which subscription is required), is clearly an early Colt Model 601. It has several classic 601 features such as the duckbill flash suppressor, cast front sight base, and brown molded fiberglass stocks (which were factory overpainted green on most 601s, but the green paint is not evident on this one). In addition, the forging line of the magazine well appears to line up with the forging line’s continuation on the upper receiver, although this is hard to judge from the image we’ve got.

The duckbill on this example of the rifle appears to have been modified into a stepped configuration. We’re unaware of the purpose of this version of flash suppressor, if it really is a version and not just an artifact of the degradation of this image through multiple modes of reproduction. (Somewhere, there’s the original 4″ x 5″ Speed Graphic negative of this picture, and accompanying metadata about who took it, when and where — but we haven’t got it).

Shall we read what 635B said, back in 1963, about the M16?1

DESCRIPTION AND APPLICATION

The M16 rifle is a commercial lightweight, gas-operated, magazine-fed shoulder weapon designed for selective semiautomatic or full automatic fire. It is chambered for the .223 caliber cartridge and is fed by a 20-round box type magazine. It is equipped with an integral prong-type flash suppressor and fiberglass stock and handguard. A bipod, which attaches to the barrel at the front sight, is available as an accessory to the rifle. The M16 is used by the Army and the Air Force.

PHYSICAL AND PERFORMANCE CHARACTERISTICS

Weight, without magazine: 6 lb. (approx.)

Weight of magazine, empty: 4 .7 oz.

Weight of magazine, loaded (20 rounds): 12.7 oz.

Length, overall: 39 in. (approx.).

Length, barrel with flash suppressor: 21 in.

Rate of fire: (automatic) 650 to 850 rpm.

Sight radius: 19.75in.

Trigger pull: 5.5-7.5 lb.

Type rear sight: Iron, micrometer.

Type front sight: Fixed blade.

Type of flash suppressor: Prong (integral).

Accuracy: A series of 10 rounds fired at a range of 100 yards shall be within an extreme spread of 4.8 inches.

AMMUNITION

CARTRIDGE, CALIBER .223: Ball (Full Jacketed Bullet).

This is the “Hello, world!” of the M16 in formal Military Standards. The previous long-gun MIL-STD, 635A of 2 Sep 1960, which was superseded by this version, contains no reference to the black rifle.

Observations on the Standard

A MIL-STD is supposed to be the absolute doctrinal statement of what an article of military equipment is (and that is one reason it’s fairly high-level: to allow minor changes to be made without having to rewrite the standard every time the factory or the military comes up with a minor improvement). But this standard contains both vague entries and an erroneous one, neither of which is expected.

The vague entries include the very dimensions of the rifle: its length and weight are listed as “approximate.” This hints that the standard writers may have been working off third-party data rather than their own trusted measurements.

One could quibble with the definition of the screw-on flash suppressor as “integral.” Looking at this and other MIL-STDs, it seems clear that the authors make a distinction between flash suppressors that are issued as a component of the weapon and not meant to be removed by the end user, like those of the M14 and M16, and those meant to be add-on or field-detachable accessories, like those for the M1 Carbine and M3/M3A1 submachine gun.

There are also one outright error in the standard. The sight of the M16 is described as a fixed blade; actually, it is an adjustable post. A handful of very early AR-15 prototypes may have had a fixed blade, as the original AR-10 did (well, technically, the AR-10’s is drift-adjustable for windage); but even by the time of the Project AGILE tests of AR-15s (Colt 601s) the elevation-adjustment on the front sight was standard.

Tentative Conclusions

This MIL-STD and its somewhat wobbly description of the early M16 probably resulted from the standard writers having spec sheets and no weapon, or a very early prototype, and took place before the Army won its battle to add a forward assist (as they put it, a positive bolt closing) to the firearm. (Or, conceivably, the standard-writing overlapped chronologically with this effort). Since the Standard had to wend its way through several levels of approval2 in the leisurely manner of a peacetime draft military, and needed sign-off from all the services, there appears to be a considerable lag between changes to the actual rifle and changes to the description of the rifle in the MIL-STD.

MIL-STD 635B’s description of the M16 was the supposed standard, but had little bearing on what the Army ordered and got: that was driven by the contract with Colt (and the other subcontractors), and the interplay between manufacturing personnel and the Contracting Officer’s Technical Representatives (COTRs, pronounced “CO-tars”) who were the .gov officials interfacing with them. Through these contractual interactions, and constant pressure from improvements from the ranks, the M16 would be considerably modified by the time it got its own dedicated military standard, ten years later.

Notes

1. MIL-STD-635B: Military Standard: Weapons, Shoulder (Rifles, Carbines, Shotguns and Submachine Guns). Department of Defense. Washington, 7 Oct 1963. p. 6 et seq. Note that there were and are separate MIL-STDs for hand and shoulder weapons (handgun standard at the time was MIL-STD 1236 from 1960). Both standards were withdrawn in January, 1974 and not directly replaced. Instead, individual standards were created for specific weapons. Standard MIL-R-45587A covered the M16 and M16A1, and was issued (finally!) on 02 Mar 73.

2. The levels of approval included DOD and Service Department authorities (Army, Navy and Air Force; USMC and USCG small arms were controlled by the Navy). The standard itself was written by the Headquarters, Defense Supply Agency, Standardization Division, Washington, D.C.; the service components designated as “custodians of the standard” were, in presumed order of authority, the Army Weapons Command, the Bureau of Naval Weapons, and the Warner Robins Air Materiel Area. In the intervening 50+ years, all of these organizations have been reorganized and renamed.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

3 thoughts on “The M16 as First Standardized”

The orginal three-pronged flash suppressor was indeed thinner than the later ones; I think some in the retro community refer to the early ones as duckbills, and the later thicker ones as simply three-pronged.

I have examples of both kicking around here, both on guns and loose. Sounds like a future feature.

Looking forward to it. I think, perhaps, you may be familiar with this guide:

http://www.ar15.com/forums/t_3_123/241681_0Colt_s_USGI_M16_series_variation_guide_edition_IV.html

Unfortunately I am insufficienly technically literate to hot link it.