We’re going to try to return to our former practice of posting this list once a week. The list was a life’s work for retired Special Forces Command Sergeant Major Reginald Manning. Reg was beloved for his sharp mind and sense of humor; among other tours he survived one at what was probably the most-bombarded SF A-Camp in the Republic of Vietnam, Katum. (“Ka-BOOM” to its inmates). As a medic, some of Reg’s duties in the camp were not a joking matter, and that’s all we’re going to say about that.

We’re going to try to return to our former practice of posting this list once a week. The list was a life’s work for retired Special Forces Command Sergeant Major Reginald Manning. Reg was beloved for his sharp mind and sense of humor; among other tours he survived one at what was probably the most-bombarded SF A-Camp in the Republic of Vietnam, Katum. (“Ka-BOOM” to its inmates). As a medic, some of Reg’s duties in the camp were not a joking matter, and that’s all we’re going to say about that.

There is a key to some of the mysterious abbreviations and codes, after the list.

May God have mercy on their souls, and long may America honor their sacrifices and hold their names high in memory.

|

Year |

Mo. |

Day |

Rank |

First |

Last |

Unit |

Code |

Nation, Location, Circumstances |

|

1967 |

02 |

20 |

WO-2 |

Max P. |

Hanley |

AATTV |

KIA |

SVN; A-113, Mobile Guerilla Force, 5 Km SE of A-104, Ha Thanh, at OP66, Quang Ngai Prov. |

|

1967 |

02 |

20 |

E-6 SSG |

John E. |

McCarthy |

11C4S |

KIA, DSC |

SVN; A-302, Mike Force, Phuoc Long Prov., near A-341, Bu Dop |

|

1969 |

02 |

20 |

E-5 SP5 |

Alan C. |

Burtness |

11B4S |

KIA |

SVN; 4 MSFC, Can Tho, Phong Dinh Prov., by a mine |

|

1967 |

02 |

21 |

E-7 SFC |

Domingo R. S. |

Borja |

11C4S |

KIA, BNR, DSC |

Laos; CCN, w/ RT??, YD188011, 20k west of A Luoi |

|

1967 |

02 |

21 |

E-7 SFC |

Billy E. |

Carrow |

12B4S |

DNH, accident w/ weapon |

Thailand; 46th SF Co, A-4634, Trang (Camp Carrow near Trang named for him.) |

|

1968 |

02 |

21 |

E-7 SFC |

Robert N. |

Baker |

11C4S |

KIA |

SVN; CCN, FOB1, Quang Nam Prov. |

|

1968 |

02 |

21 |

E-6 SSG |

Paul M. |

Douglas |

11B4S |

KIA |

SVN; CCN, FOB3, RT Hawaii, Quang Tri Prov., killed by mortar round at Khe Sanh |

|

1965 |

02 |

22 |

E-5 SP5 |

Gerald B. |

Rose |

12B2S |

KIA |

SVN; A5/214, Soui Doi, Pleiku Prov., at Mang Yang Pass |

|

1967 |

02 |

22 |

E-7 SFC |

George W. |

Ovsak |

11C4S |

KIA |

SVN; A-302, Mike Force, at A-301 Trang Sup, XT177554, unloading boobytrapped truck |

|

1969 |

02 |

24 |

E-7 SFC |

Charles E. |

Carpenter |

11C4S |

KIA |

SVN; 2 MSFC, B-20, 261 MSF Co, just outside A-244, Ben Het, Kontum Prov. |

|

1968 |

02 |

25 |

E-7 SFC |

Lawrence F. |

Beals |

11F4S |

KIA |

SVN; 1 MSFC, A-111, Quang Nam Prov., convoy between Da Nang and A-109, w/ Tomkins |

|

1969 |

02 |

25 |

E-7 SFC |

James K. |

Sutton |

11B4S |

KIA, DOW |

SVN; C Co, 5th SFG, w/ ??, radio relay site w/ USMC at FSB Neville near DMZ, Quang Tri Prov. |

|

1970 |

02 |

25 |

E-7 SFC |

Bobbie R. |

Baxter |

12B4S |

DNH, vehicle crash |

SVN; B-53, Bien Hoa Prov., S-4 NCOIC |

Here is the key to the status codes for the Causes of Death or Missing in Action, and also a decoder for some of the common abbreviations:

SVN SF KIA Status Codes:

BNR – Body Not Recovered. (Known to be dead, but his body was left behind).

DOW – Died of Wounds. (At some time subsequent to the wounding, days/weeks/months).

DNH – Died Non-Hostile. (Accident, disease. There’s a couple suicides among them).

DWM – Died While Missing. (Usually implies body recovered at a different time during the war).

KIA – Killed In Action.

MIA – Missing In Action.

PFD – Presumptive Finding of Death. (This was an administrative close-out of all remaining MIAs during the Carter Administration).

Common Abbreviations

A-XXX (digits). SF A-team and its associated A-camp and area.

AATTV – Australian Army Training Team Vietnam. Their soldiers integrated with SF in VN.

BSM, SS, DSC, MOH: Awards (Bronze Star, Silver Star, Distinguished Service Cross, Medal of Honor).

CCC, CCN, CCS. Command and Control (Center, North and South). Covernames for the three command and support elements of the Special Operations Group cross-border war.

MGF – Mobile Guerrilla Force, indigenous personnel led directly by US.

MSFC – Mobile Strike Force Command, indigenous personnel led directly by US. Aka Mike Force.

We’ll cheerfully answer most other questions to the best of our ability in the comments. Note that (1) it’s Reg’s list, and we can’t ask him any more, and (2) it was Reg’s war, not ours, and all our information about SF in the Vietnam war is second hand from old leaders and teammates, or completely out of secondary sources.

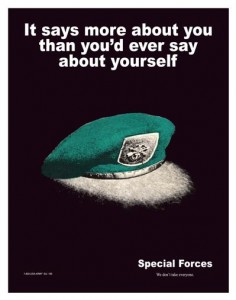

Some of the Best Fail Selection

Interesting thing about the selection programs for SF and other Special Operations Forces: most of the guys who could probably pass don’t even try.

Interesting thing about the selection programs for SF and other Special Operations Forces: most of the guys who could probably pass don’t even try.

And most of the guys who do try and don’t quit probably could make it. You see, there’s four ways out of SFAS (or any of these deals).

- You can pass, the outcome everyone wants and hopes for, but not everyone gets;

- You can quit, in SF vernacular “VW” (voluntary withdrawal), in which case you get the dreaded “NTR letter” (Never To Return). The “Never” can be a little rubbery for a soldier that subsequently displays considerable character growth, though.

- You can fail for good, making it all the way to the end but not selecting, and receiving an NTR letter. (This is often the case when the many cadre observing proceedings take a view you’re not giving 100% or not a team player. Being a Spotlight Ranger is a great way to collect an NTR).

- You can fail for now, making it all the way to the end, not selecting, but being invited to try again. (Sometimes after a fixed interval of months or years). This is usually reserved for people who may nonselect for youth or inexperience, or who struggled with some aspect(s) of the assessment and selection process, but who favorably impressed the cadre with their character and persistence.

After many years of running these courses, the cadre are surprisingly skilled at selecting the youth who lacks maturity now and his peer who’s never going to be teammate material.

One reason Big Green kind of hates SF is because good conventional troopers and officers who go to SFAS and get NTR’d often sour on the Army. They either turn to dirtbags (the index case being Timothy McVeigh) or just get demoralized and get out.

An NTR does’t mean you’re worthless. It just means that this, and you, don’t fit together. A lesson a guy can’t learn unless, or until, he tries.

At Breach Bang Clear, there’s a remarkable and thoughtful appreciation of the SFAS experience from Eric Hack, a soldier who attended and failed to select — and yet, found it a positive, growth-catalyzing experience. Hack was a full-length non-select, but wasn’t NTR’d, and he hopes to return some day. We think that he is displaying the kind of maturity that his future ODA will welcome. (And believe it or not, whatever MOS you come from, wherever you have served, the time will come when your experience is pure gold to your teammates). Here’s a taste:

The rest of the day was a blur. I threw that set of ACUs away, took a baby wipe shower, brushed my teeth, and I think I took the psych test and IQ tests next (but those days all seemed to roll into one). I remember a safety brief on the “Star” land-nav course and the cadre talking about all the scary venomous snakes around, trying to get some of the less committed to quit right there. I grew up on a Missouri farm and knew how to handle snakes. I was more concerned about wandering onto some backwoods moonshine distillery and dealing with Ol’ Bubba.

The Star Course excited me. I was pretty skilled in map tracking and land navigation, and the Star Course marked the exact middle of the 14-day selection course. In 2008, the JFK Special Warfare Center and School experimented with shortening Special Forces Applicant Selection (SFAS) from 21 to 14 days in an attempt to get more soldiers in the Q-Course and more SF troops on the battlefield. The experiment was roundly rejected by the cadre. They warned us on Day 0 they were going to be extra critical because they wanted the experiment to fail. In this they were successful. Only ten percent of our 401 candidates completed the course. ….

I carried my rubber duck replica M-16A2, old LC-2 suspenders, a web belt, two one-quart canteens, an eighty-pound ruck with e-tool and two two-quart canteens on the sides, an additional three-liter CamelBak on top, and all the rain and sweat my equipment could soak up.

I was cold, hungry, tired, and sick. I would routinely look at the stock of my rubber rifle to read the words a previous candidate carved: “KEEP GOING.”

Amen to that.

…even though I was miserable and the 18D was jacking with me, I was having the time of my life. Some might see that guy as an asshole, but I got the message: he wanted me to succeed, but the only way he would help me was by pissing me off. He wasn’t there to encourage or coddle me. He was there to challenge me and let me prove I had what it took to earn the right to go to the Q-course.

But while that excerpt is all fine and good, you really ought to Read The Whole Thing™. We can assure you that Eric suffered considerably to be in a position to write it. And he’s got the guts to want to go suffer again. (A lot of guys pass selection on a second pass, and some take more than that). Pure pigheaded stubbornness is a Regimental value, in the Special Forces Regiment.

Fighter / SF Soldier Tim Kennedy Retires

From the ring, that is. He’s still in as a part-time soldier, and there’s a story in that. Tim was on active duty in Special Forces when he first began to fight in mixed martial arts competitions. The command took no notice.

From the ring, that is. He’s still in as a part-time soldier, and there’s a story in that. Tim was on active duty in Special Forces when he first began to fight in mixed martial arts competitions. The command took no notice.

Then, he began to win. A lot. The command discovered that one of their warriors was actually one of the world’s top fighters. They should have celebrated their good fortune and wrung a PR and recruiting windfall out of it. (What Would The SEALs Do?) But no, that’s not what they did.

They ordered him to quit.

Instead, he quit active duty, continuing to serve in the National Guard, and kept fighting. A recent deployment and the associated pre- and post-deployment activities kept him out of the ring for a couple of years, and when he went back in the ring, he lost… and he knew that this was it.

Every athlete knows that there will be a time to hang up the gloves (or whatever). Some receive that signal when it comes in, embracing a graceful end to a young person’s career. Some don’t, and become that guy, hanging around trying to capture the feeling of ever-more-distant glory. Tim wasn’t going to be that guy.

Sitting in the ER at Saint Michael’s hospital in Toronto, Canada after my fight, I looked up at my buddy Nick Palmisciano who had ridden in the ambulance with me. He is a friend I didn’t deserve and guy that stood with me from the beginning. Fighting is a lonely thing. You train with your team. You bleed with them. You trust your coaches but ultimately you are in the cage alone. This wasn’t our first time in this situation and thankful I had someone by my side. We had been here a few times in our past decade together. Sometimes for wins and sometimes for losses. The end result always looked the same: Nick carrying five bags that should have been split among three corners and me and my face are bleeding and swollen.

“That’s it man,” I said. “We’re all done.”

We had talked about it a lot over the past few years. I’d spoken to Nick, to my wife Ginger, and to Greg Jackson and Brandon Gibson ad nauseam about the coming end. No matter how hard I trained, I knew this ride wouldn’t last forever. But saying it out loud definitely brought me both sadness that this chapter was complete and overwhelming relief that it’s a decision I could make without worrying about taking care of my family.

I had just lost to Kelvin Gastelum, a really respectful and hard-working young fighter who went out and did all the things I consider myself good at, but did them better. He actually reminded me of me when I was younger, except I was kind of a jerk back then. As losses go, I was kind of happy I lost to a guy like him.

A lot of my coaches, friends and fans immediately tried to build me up again. “Kelvin has the right skillset to beat you and it was your first fight back.” “You had ring rust.” “You’re still a top 10 middleweight.” I appreciated their comments and I don’t think they are wrong. I know I am still a good fighter. I know I was away a while. But they didn’t feel what I felt, and that’s being 37. I felt like I was in slow motion the entire match. I felt tired for the first time ever in a fight.

I’m the guy that once graduated Ranger School – a place that starves you and denies you sleep for over two months – and took a fight six days later in the IFL and won. I’m the guy that is always in shape. And I was for this fight. I worked harder than I ever have before for this fight. But I wasn’t me anymore. My brain knew what to do but my body did not respond. I’ve watched other fighters arrive here. I’ve watched other fighters pretend they weren’t here. I will not be one of them.

Do Read The Whole Thing™ at Tim Kennedy’s Facebook page. He is, it turns out, a gifted writer, and the whole thing is worth reading.

We at WeaponsMan.com wish Tim Kennedy all the best in his future endeavors. He leaves like he entered, and like he fought: with heart, class and sportsmanship.

He may never step into the ring again, but his name lives for evermore.

That colonel that demanded that he quit UFC, what was his name? Dunno. We forgot.

Gift for the SF Gunslinger

These magazines are for sale on GunBroker. While actually in SF, we could never have used these operationally, as they’re a rollicking OPSEC violation as they sit there shining at you, but we think they’re hell for cool:

Yep, SF crest (officially, “Distinctive Unit Insignia,” which yields an unfortunate acronym) engraved magazines. Back in the day, we could have rocked ’em only on the range, as most operational use required unmarked if not sterile arms and equipment. But now, they’re just the thing for a retiree’s gun bag.

Of course, if you’re, say, the Frogmen or MARSOC, you’re going to buy a couple of these to drop any time you do a Blackwater and plug the wrong locals, sending the nearest SF unit into the DAMN drill:

- Deny everything

- Admit nothing

- Make counteraccusations, and

- Never change your story!

The seller says:

Black Teflon coated mil-spec 30 round mags with PSA marked floor plates and gray MagPul Anti-tilt followers. These mags are manufactured by D&H, very HIGH quality materials! All images are engraved on the lower right side of the mags. These are DEEPLY engraved for a lasting bright image, cheaper laser equipment etchings may fade with time, NOT THESE!!

We accept VISA/MC USPS Money Orders, bank checks, cashier’s checks and personal checks. Personal checks held for 7 days. $7 USPS priority shipping. NO CREDIT CARD FEES. All laser engraved magazines etched in our laser shop when ordered, we do not buy them from a third party, these mags will usually ship in 3-5 days depending on laser shops workload.

We’ve handled but not shot D&H mags, and they looked good at the time. The guys running them were having no trouble with ’em.

Of course, they can’t ship them to Libya, Iran, North Korea, Massachusetts, New York, California, and places like that.

We’re not going to order any of them for, say, 12 hours, to give our SF readers the chance to go first. Although one suspects that however many of these he sells, he’ll happily make more.

Update

If you’re not SF, maybe you’d like their USMC Eagle, Globe & Anchor mags, or mags with the Air Force logo, a Navy fouled anchor, or a laser engraved American Flag.

The Dumbing Down: Lower the Standards to Meet the Men

Recently, frequent commenter JAFO reminded us on Gab of the disaster that was MacNamara’s 100,000. This was a 1960s attempt to use the Armed Forces for social engineering by deliberately admitting 100,000 volunteers a year who did not meet minimum standards for volunteers or the draft. What kind of standards? Today, the standards the services’ recruiters struggle to meet are fitness standards, given the latest Rotund Generation, and medical standards, given the universalization of psychoactive drugs. (And yes, social engineers decry those standards, but that’s a whole other issue). But fifty years ago, with a much larger military and an active draft, the people who wanted in but could not get in were disqualified, mostly, by low IQ.

They were too dumb to grunt. Process that.

First, some background. Army mental standards are not especially high, although they vary from job to job. They divide the population into bins based on standard deviation from the mean. The bottom bin (Category V) and the next-to-bottom (Cat IV-B) are not ever supposed to be admitted. In 1966, the harsh term used for these people was mentally retarded. For the IV-Bs, perhaps, educable mentally retarded. Since then, we’ve had so many iterations of euphemisms, with each one in turn flaming out as the truth of it burns through, that we’re not really sure what the buzzword du jour is. It doesn’t alter the fact that these recruits could not do much meaningful military work in the far lower-tech Army and Marines of 1966, and they’d been even less useful now.

The next group up, Cat IV A, are admitted when the personnel wallahs are desperate for warm bodies. During the Vietnam War, for example, and during the Hollow Army of the mid and late 1970s. These are the ones the compassionate educator termed, fifty years ago in 1966, borderline retarded.

Warm body desperation is a pathology all its own, given the highly incentivized recruiting realm, where carrots and sticks are both wielded with abandon by Recruiting Command. There are frequent test-cheating and recruiting corruption scandals as it is, most of which somehow involve tests being pencil-whipped or ringers being substituted at test time so that Slow Joe can become GI Joe. So some of these people scrape through or are smuggled through, all human-devised barriers being, ultimately, porous to incentivized human ingenuity.

IQ is highly correlated with a lot of things in life, from earning potential to impulsivity to educational attainment to crime. In fact, most psychometricians know, although few would write it down and nail it to the cathedral door, that a great deal of interracial disparities in outcomes of all kinds are downstream of interracial disparities in IQ.

Most people tend to sort themselves into groups of people of similar IQ. A Great Assortation has taken place since World War II. We mate with similarly smart spouses; we move to neighborhoods full of people much like ourselves; we work in offices full of people with similar levels of intelligence and education. Only people in public-facing jobs see the full range of human diversity in intellectual ability. Thus, because our personal heuristic field is rationally bounded by the people we know, and the people we know are not representative but are from a restricted range of a wider distribution, we’re likely to misjudge where “average” is and just how far it is to rock bottom.

We’ll get back to that, but first let’s talk about the history of The Dumbing Down.

MacNamara’s 100,000

In the mid 1960s, Robert S. Macnamara (the S. was, suitably, for “Strange” — we are not making that up), decided that the Army and Marines could cure some of the problems of underperforming civilian youth by giving 100,000 dummies a year an opportunity to excel in uniform. The project was successful at recruiting or drafting 385,000 people with IQs as low as 62 (!) into what Salon calls “McNamara’s Morons.” As you might expect, these pitiful privates did not excel in the military, and were disproportionately represented among courts martial and NJP’d troops.

FMI on Mac’s Morons, this weird site suggests it was a white man’s plot to exterminate black men, but it’s worth checking out the period (1968) New York Times story embedded therein, about the outcomes for the substandard soldiers. This dictionary entry from the Vietnam Project at Texas Tech gives a concise and neutral explanation. This Master’s Thesis from the University of Utah[.pdf] illustrates what happens when a modern, poorly educated but credentialed social justice warrior examines this through the usual SJW prisms of racism and marxist jargon.

The Colin Powell Commission and SF

In 1993, the first Clinton Administration wanted to start small in social engineering and work their way up. One of the first things the social engineers wanted to arrange in the military is ,not to put too fine a point on it, more minorities in Special Forces. Why this was necessary was so obvious to them that they couldn’t explain it rationally. All they could do, if you asked “why?”, was to label you racist and shriek at you — even though you were not the one trying to structure things racially. If pressed by some “racist,” they had slogans — you know the type. “Diversity is Our Vibrancy.”

In 1993, the first Clinton Administration wanted to start small in social engineering and work their way up. One of the first things the social engineers wanted to arrange in the military is ,not to put too fine a point on it, more minorities in Special Forces. Why this was necessary was so obvious to them that they couldn’t explain it rationally. All they could do, if you asked “why?”, was to label you racist and shriek at you — even though you were not the one trying to structure things racially. If pressed by some “racist,” they had slogans — you know the type. “Diversity is Our Vibrancy.”

Now, SF was at the time at least 40% minority, but these were the wrong minorities. SF had a lot of Hispanics. Lots of Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Central Americans, Tex-Mex border guys. We also had some other minority groups at higher-than-national average counts, including Asians, American Indians, Pacific Islanders, and Jews — when these four groups were extremely underrepresented in Big Green as a whole.

These “minorities” were invisible to the Clintonistas, who counted them all as “white.” (Fair cop, as far as the Jews and most of the Spanish-speakers, some of whom barely had a functional command of English, were concerned). “Minority” meant “black,” another one of those metastasizing euphemisms. (Remember, this was 1993; today, they’re “African Americans.” Do try to keep up, Winston Smith).

The only “minority” anybody in the Clinton Pentagon could think of was Colin Powell, who had become a media hero for being the spokesman during the Gulf War. So they found General Powell and set him at the head of a commission looking into the desperate straits of Diversity is Our Vibrancy in Army Special Operations, especially SF.

During Powell’s career, which stretched from the sixties to the nineties, the percentage of blacks in the Army and in the combat arms had declined. One explanation (for the diversicrats, the only explanation) was deep-seated institutional racism. Which is why Powell was terminal at Lieutenant Colonel… oh, wait. Another explanation gave America a little more credit: in 1966, a bright black kid really did face a tough future, and one way forward that had a concrete set of rules and that did its imperfect best to treat all citizens alike was the armed services. It was a great pathway to the middle class for people who didn’t have another. But by 1996, their sons (and daughters) had other pathways. Colleges wanted them, employers wanted them, and the Armed Services were just one more option, not the standout option they’d been to Dad or Uncle Mike.

But Powell, at his core an honest man, didn’t come up with a bullshit report, but rather, with two possible structural changes in SF recruiting standards that might meet the quotas-not-quotas envisioned by the politicians.

Two things were keeping “minorities” out of SF, Powell said: the swim test, and the GT Score or IQ cutoff. An SF volunteer has to swim the length of a pool and back (although at least once they passed a guy for walking the whole thing on the bottom and periodically sounding for air like a marine mammal, because he was such a will-not-quit dude), and an SF guy has to be about one standard deviation above mean IQ. (Technically, GT 110, with GT 100 normed to the mean).

Now, for reasons known but to God (but that we’re going to offer informed speculation about here), blacks come to the Army less likely to be able to swim, statistically speaking, and they have a harder time learning to swim. Army diversicrats (a vast and extremely pampered group these days) have a bunch of nonsense about inner city kids, victims of racism, no swimming opportunities, yadda yadda. In the NCO corps, this same idea was more pungently expressed that “some kids played in the swimming pool, some kids played in the fire hydrant,” and there might be some truth in it.

But in our experience, a bigger swimming problem for black SF recruits was biology. Ceteris paribus, young black men have considerably less body fat than their white or Asian cohort. This translates quite directly into less buoyancy, making learning to swim both more difficult and more frightening than it is to your training teammates.

The swim test could probably be dispensed with, although it is very, very useful to be a strong swimmer in many surprising military situations. But SF guys work in teams; the water lovers self-select onto scuba or maritime operations teams, and on any other team, one weak swimmer or two is just something the team sergeant keeps a mental note of — one hopes the guy has other, strengths (as anyone who makes it through SF training tends to do). Nobody liked it but they saluted and carried on.

The IQ test was different. There is no place for a dumb SF guy, and the average team house probably has a higher average IQ than the liberal arts faculty at a state university. The guy you thought was your team’s village idiot was at least one standard deviation at least above the general run of humanity.

Moreover, the diversicrats knew the toxic effect of just lowering the GT Score — the military test’s IQ equivalent — for the desired minorities, would serve to flag members of that minority as “probably dumb,” and engender rather than diminish discrimination, unfairly, especially against the guys who were already capable of meeting the extant standard. (Mind you, there was no evidence for discrimination, just uneven volunteer rates and pass rates by race). So they did something that the guys hated even more — they lowered the IQ gate for everybody. This meant a rivulet of borderline black recruits amidst a Niagara of borderline whites.

And we waited, out in the team rooms and company HQs, for the deluge of idiots (actually, average-IQ men) to the teams. But it didn’t happen. What happened was this: completing SF training, too, had always been highly correlated with IQ or GT Score. So more dumb (really, average) guys entered the training pipeline, but almost all of them flunked out, or dropped out. The Army just wasted a ton of money encouraging good but not-SF-material guys to try out. Even more unfortunately, the experience soured some of them on the Army overall, depriving who knows how many conventional companies of competent commanders, and platoons of solid sergeants, down the line?

After some years, and the departure of the Clinton suits (although they left behind plenty of sporulating diversicrats in the civil service ranks) the GT score gate was put back up, at least partially. We don’t think about the racial make-up of the SF Regiment today, but it’s probably about where it was in 1993, 60% white, 40% minority, maybe 5-8% of those minority guys being black. But they all met a known standard, and that’s solid gold in a profession where intramural trust is paramount.

They’re now saying that recruiters have to be able to recruit troops with criminal records. You know, for Diversity. Because Diversity is Our Vibrancy.

No.

The Department of Justice Today and Police

And now, we have the Department of Justice arguing in a position paper on Advancing Diversity in Police Hiring (press release and .pdf) that we need to turn the cops into a modern equivalent of MacNamara’s Morons, plus we need to stop doing background checks on candidates because Diverse Vibrancy candidates are more likely to be felons and/or gang members. Therefore, being a felon or gang member, says DOJ, should not be a DQ.

Gee… even MacNamara just hired retards, not retarded felons.

Black Ops Matter

Here’s a charity T-shirt sale that we can recommend without reservation: these Black Ops Matter T-shirts we’re originally made for an annual fundraiser for the families of fallen special operations and clandestine service personnel, Spookstock.

Here’s a charity T-shirt sale that we can recommend without reservation: these Black Ops Matter T-shirts we’re originally made for an annual fundraiser for the families of fallen special operations and clandestine service personnel, Spookstock.

Yes, it’s really a thing.

They were so popular at Spookstock, that the limited stock (spook stock?) on hand sold out. So a second fund raiser was created and run. Every dollar collected, over and above costs, goes directly on a 50/50 split to two worthy foundations: the special operations warrior foundation, or the clandestine service foundation.

These foundations support the family members of fallen operators and intelligence officers; for instance, by providing college scholarships. You’d think that a grateful government would do that, but you’d think wrong. So these two foundations stood up — SOWF first, initially to deal with the kids of the eight men killed at Desert One on a fruitless hostage rescue attempt in 1980. Since then, there’s been some mission creep of a good kind, providing greater benefits to a wider range of widows and orphans, as the endowment has grown. A group of clandestine service retirees, seeing the good that SOWF was doing for their uniformed counterparts’ families, realized that the civilian intelligence officer community needed something similar, too, and so a parallel organization was born, the CIA Officers Memorial Foundation.

Plus, the T-shirts are kind of cool. We ordered two.

Rough Time for SF Over There, and Here

We’ve been losing a lot of people (for us), and other SOF units have been hit hard as well. Multiple deaths in SF are rare, and with such a small group, every death stings. The absolute lack of regard or respect from the E-Ring for the actual guys being sent to these actions stings additionally. Here’s two of ’em, from 10th Group:

Capt. Andrew D. Byers, 30, of Rolesville, N.C., and Sgt. 1st Class Ryan A. Gloyer, 34, of Greenville, Penn., died of wounds sustained while fighting enemy forces in Kunduz, Afghanistan, the Army says.

Byers and Gloyer — Green Berets — were assigned to Company B, 2nd Battalion, 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) at the Mountain Post. Both were posthumously awarded the Bronze Star Medal and the Purple Heart Medal, according to a Fort Carson spokeswoman.

Here’s a little more on Byers, originally from upstate New York. Young, upcoming guy. His father says:

My son was the commander of a Special Forces HALO team and this was his third deployment. He was scheduled to return in early December. Special Forces was his dream. He was a good kid and grew to be a great man.”

He’s survived by a twin sister in New York and a wife and family in North Carolina.

Konduz was 100% pacified by December, 2001. We didn’t have a guy get shot at there for a good ten years. Now it’s Game On; along with Byers and Gloyer, four other Yanks were wounded, and dozens of Afghans killed and wounded alongside them. They were hit hard as soon as they disembarked from utility helicopters and fell to small arms fire.

There was another guy, a medic, who fell in a green-on-blue recently.

One frustrating thing about this is the complete absence of this war in the priorities of those who, for personal aggrandizement or greed, make themselves “leaders.” Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter doesn’t care, although he would if the guys wanted breast implants rather than air support. He’s focused on social engineering and always has been. The President doesn’t care — he’s more concerned about the cares of criminals sent to prison for actual crimes.

The candidates for President don’t care. One of them wants the wars to stop, and the other, who has a couple of wars that practically have her own name on them, is well known for her contempt for those who fight them: when one dies, “what difference does it make?” It doesn’t put money in her family’s pocket. so it’s of no consequence.

Inserted Update

We knew there was another casualty we wanted to mention. SSG David Whitcher died in a training mishap in open water at the SF Combat Diver Course in Key West. After 5 years in the NH National Guard, Whitcher went active duty in 2013 and volunteered for SF in 2015. He graduated from SFQC this year, and was assigned to C/2/7th SFG(A) at Eglin AFB before transferring to the SCUBA school unit, C/2/1st Special Warfare Training Group.

We knew there was another casualty we wanted to mention. SSG David Whitcher died in a training mishap in open water at the SF Combat Diver Course in Key West. After 5 years in the NH National Guard, Whitcher went active duty in 2013 and volunteered for SF in 2015. He graduated from SFQC this year, and was assigned to C/2/7th SFG(A) at Eglin AFB before transferring to the SCUBA school unit, C/2/1st Special Warfare Training Group.

The school commander, MG James Linder, called Whitcher’s death, “a sobering reminder of the dangerous training our soldiers undertake to prepare themselves for the rigors of Special Forces.” Fair enough, General. We extend our condolences to his family, friends, and teammates in this unhappy time. Let us celebrate his life.

/end of Update.

Meanwhile, SF’s history got hit hard at home. Drew Brooks in The Fayetteville Observer:

Filing cabinets sit open with fans trained on the papers inside.

Books have been piled up to be sorted and salvaged at a future date.

They sit atop display cases, filled with patches, berets and artifacts from wars from Vietnam to Iraq and Afghanistan.

Cliff Newman walks through it all, occasionally pausing to thumb through a book or peak at debris stored in plastic bags.

“We’re still kind of in a state of shock,” he said.

Newman, executive director of the Special Forces Association, said the nonprofit was hit particularly hard by the floodwaters that came with Hurricane Matthew last month.

The 52-year-old association’s compound off Doc Bennett Road – which includes picnic areas, a memorial garden and office space – was covered in nearly five feet of water at the flooding’s peak.

Nearby Rockfish Creek, located down a steep embankment from the roughly 20-acre compound, rose 40 feet to flood all but a small chapel and rows of memorial stones, Newman said.

“It was like a big lake,” he said. “It just surged right in here and flowed back out again.”

They have calculated the surge at 46 feet. The creek is way below the location of the Association compound. But with the floods, a bend in the creek bottled up the flow just enough to trash a half-century plus of history.

There is no flood insurance. (Who gets flood insurance when the normal water line is fifty feet lower?) but basic insurance will cover one building that engineers are calling destroyed, and repairs to another that was damaged. Even today, power, computer networking, and water to the site have not been fully restored. It’s a colossal mess.

SFA has since gotten some professional help with some aspects of the recovery. After several years of database pruning and maintenance, the Association’s data was in good shape, but there was no off-site back-up; the hard drives are supposed to be passed to a specialized recovery firm.

Saddam’s Revenge?

“It’s a little stale,” Newman said, commenting on the musty smell of the once-flooded building.

Parts of the walls are missing. Each room is stacked with piles of debris, some of which will be salvaged. Some is too destroyed to keep.

Ruined electronics are stacked amid piles of plastic bags, destroyed magazines – archives of the association’s quarterly Drop magazine – and documents which dated to the 1960s.

In another room, a bust of former Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, one arm outstretched, gazes at the damage.

Awards and mementos from many a Special Forces career are disheveled amid the still-drying display cases. Photos and posters, some decades old and tracing the history of Special Forces, are stacked on top of them.

There are flags, uniforms and traditional clothing from around the world.

“Some of this is salvageable and some isn’t,” Newman said. “Some of this is irreplaceable. It’s history.”

Well, so is Saddam. And the Association will rebuild.

CIA Issues Declassified Bay of Pigs Report — with a Disclaimer

Many years after the event, the CIA had an in-house historian, Jack Pfeiffer, write a five-volume secret history of the Bay of Pigs invasion, and has previously declassified four of the five volumes. The draft fifth volume, which reviews the CIA Inspector General investigation from a 20-years-later perspective, was never revised or approved before the death of the historian drew a curtain on the project. The reasons that the CIA never pursued the completion of this report may be debated. Our opinion is that this volume reflects an opinion which lost out at HQ, the opinion that they key decisions leading to the failure of the operation were not errors made by the CIA in-house staff whom the IG report blamed for the failure, but the ratcheting restrictions on air strikes and air support, which were imposed for political reasons by Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy.

Many years after the event, the CIA had an in-house historian, Jack Pfeiffer, write a five-volume secret history of the Bay of Pigs invasion, and has previously declassified four of the five volumes. The draft fifth volume, which reviews the CIA Inspector General investigation from a 20-years-later perspective, was never revised or approved before the death of the historian drew a curtain on the project. The reasons that the CIA never pursued the completion of this report may be debated. Our opinion is that this volume reflects an opinion which lost out at HQ, the opinion that they key decisions leading to the failure of the operation were not errors made by the CIA in-house staff whom the IG report blamed for the failure, but the ratcheting restrictions on air strikes and air support, which were imposed for political reasons by Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy.

This position was, i n official Washington where the Kennedys are beatified if not sanctified outright, a question of canon law: heresy in the first degree. Yet, the IG report (which the historian is criticising here), took such a partisan pro-Kennedy position as to assume the President (a combat veteran) and Attorney General were unaware of the need for air superiority over the beachhead.

n official Washington where the Kennedys are beatified if not sanctified outright, a question of canon law: heresy in the first degree. Yet, the IG report (which the historian is criticising here), took such a partisan pro-Kennedy position as to assume the President (a combat veteran) and Attorney General were unaware of the need for air superiority over the beachhead.

Referring to the cancellation of the D-Day air strike by President Kennedy on the evening of 16 April 1961, the Inspector General’s survey placed more blame on the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, General Cabell, and the Deputy Director of Plans, Mr. Bissell, than on Mr. Kennedy and Secretary Rusk-even suggesting that perhaps the President “may never have been clearly advised of the need for command of the air in an amphibious operation like this one.” (This, of course, was the position taken by Robert Kennedy during the hearings.) It was not that the President had not been advised, it was simply a case that he and Rusk apparently did not want to risk international criticism of the US.1

Cabell and Bissell, of course, were men whose opinion carried no weight with the Kennedy crowd: unlike JFK and the entire Cabinet, neither was a Harvard man (although Bissell was a Yalie).

SS Houston (and the invaders’ ammo supply) goes up in flames, destroyed by Cuban aircraft preserved by last-minute cuts to the rebel air strikes.

The two principal obstacles to success were RFK and Dean Rusk, and the historian spares Rusk not a bit:

During the meeting in Rusk’s office on the night of 16 April 1961, General Cabell clearly spelled out that unless the brigade aircraft were permitted the strike on the morning of D-Day-particularly the attack on the three air fields which contained the remaining combat aircraft-the Brigade’s shipping probably would be lost and resupply of the beachhead would be impossible. Similarly, at 0430 hours on the morning of the 17th when Cabell went to Rusk’s home and got permission to telephone Kennedy at Glen Ora to ask for naval air cover in lieu of the cancelled air strike, the criticality of control of the air over Cuba should have been obvious even to the slow witted.2

The CIA was required to release this document by legislation; it prepends a cover letter essentially rubbishing the document.

Follow-on consequences: abandoned, out-of-ammo rebels are bound by Castro militia. Castro would sell the survivors of his camps back to JFK — for millions he’d use to export his revolution.

We’re still absorbing the material in this report, but one interesting facet is the “Battle Report” drafted by a former newspaperman, Wallace R. Deuel, based on the story of the landings as told by one of the two CIA case officers with the landing force (who were under orders not to land themselves; Grayston Lynch was a former Special Forces officer, and the other case officer, “Rip” Robertson, was a Marine, both veterans of amphibious combat in WWII).

The IG’s diary contains no further reference to the Deuel report, but a 29 September 1961 Memorandum for the Record from Robert D. Shea-a member of the IG inspection team-read in part as follows:.

In June 1961, Deuel, formerly a well-known foreign correspondent for the Chicago Daily News, was requested to write the story of the invasion. He did this in about three weeks, chiefly by debriefing Grayson [sic) Lynch, who is not a “word man.” The result was a 52-page article entitled “The Invasion of Cuba: A Battle Report,” dated 4 July 1961, of which we have a copy. The request to do this job, which was transmitted to him by Mr. Kirkpatrick, resulted from a suggestion made by Admiral Burke, or another of the Joint Chiefs, in the presence of General Taylor, the DCI, and J.C. K[ing], that the true story should be written and published in order to counteract the untrue accounts that were circulating. A copy of the article was sent to General Taylor, who forwarded it to State and DOD for clearance. State’s reply, under date of 6 September 1961, was that they were against circulating this sort of article and disapproved of the contents. Deuel said that he is glad that the article was thus killed, as he felt that it was somewhat fuzzy, due to the fact that lit was not slanted for any particular magazine.3

One of the great disappointments is that the author’s questions for former CIA Director Allen Dulles, outlined in Appendix D of the report (beginning on p. 156), were apparently never asked and answered. Many of these questions remain.

Some of the rebels’ small arms, most of which were clearly of US military origin. Here, M1919A6 Browning .30-06 machine guns. In the left background, you can see the barrel of a .50 M2HB.

Why would an in-house CIA Inspector General (former operations officer Lyman Kirkpatrick) narrow the focus of his report to focus only on in-house screwups (which were, Pfeiffer agrees, considerable)? Pfeiffer suggests it was a great CIA tradition, to wit, a tawdry Headquarters backstabbing:

Both [IG staffer Kenneth] Greer and [CIA Historian Wayne G.] Jackson indicated that the IG’s survey took the form that it did because Kirkpatrick wanted Bissell’s job. This apparently simplistic view probably was basically at the heart of the matter. By focusing exclusively on internal CIA affairs, the failure of the Bay of Pigs operation could be laid on Mr. Bissell. Had the IG’s investigation taken cognizance of the changes imposed on the plan by the White House and the Department of State, Bissell would lOok to be less the villain. At risk of venturing into psychohistory, a part of the explanation of why Kirkpatrick wanted Bissell’s job is that he believed (perhaps correctly) that if he had not become physically handicapped when his career was in its ascendency, he would have been named DDP before Bissell.4

Kirkpatrick fell victim to polio in 1952, ending any prospects of advancement on the clandestine side of the house; at the time of the Bay of Pigs IG report he’d been IG for eight years and badly wanted the Deputy Director, and ultimately, Director, chair.

But yeah, you can see why the Agency was reluctant to release this, and had to be forced.

The five volumes of the Official History of the Bay of Pigs Operation include:

-

Air Operations, March 1960-April 1961;

-

Participation in the Conduct of Foreign Policy;

-

Evolution of CIA’s Anti-Castro Policies, 1951-January 1961;

-

The Taylor Committee Investigation of the Bay of Pigs;

-

[draft] CIA’s Internal Investigation of the Bay of Pigs.

All these documents, and more besides, are online in the CIA’s electronic reading room. We leave finding them (which can be a challenge in the scavenger’s hoard that is the electronic reading room) as an exercise for the reader. We have provided an OCR’d version of Volume 5 (the one we downloaded from CIA was not OCRd, perhaps they have corrected that by now) for your convenience.

Notes

- Pfeiffer, p. 33.

- Ibid.

- Pfeiffer, pp. 88-89.

- Pfeiffer, pp. 91-92.

Sources

Pfeiffer, Jack B. Official History of the Bay of Pigs Operation: DRAFT Volume V, CIA’s Internal Investigation of the Bay of Pigs.

Ave atque Vale, Charlie Aycock

Charles Aycock was a man you never forgot. If you didn’t know him, it is our mission to, by the end of this short blog post, make you regret that you did not. He made that easy,

Charles Aycock was a man you never forgot. If you didn’t know him, it is our mission to, by the end of this short blog post, make you regret that you did not. He made that easy,

He was a rare officer to have served in all components of Army SF — Active, Reserve, and National Guard Special Forces assignments; SF special mission units; and as a Department of the Army civilian supporting Special Forces.

After graduating SFOC, his initial assignment was in the National Guard 20th Special Forces Group. Volunteering for active duty and Vietnam, he served in MACV-SOG as a Hatchet Force leader and later attached to the combined interagency Phoenix Program. He served also in a variety of military free fall jobs, including as a team leader on an MFF Special Atomic Demolition Munition team.

He might have gotten a Regular commission, but he didn’t get his college degree until 1981, and then by assembling credits from here and there to get a degree from the Regents’ External Degree Program (now Excelsior University) of the State of New York. He actually did graduate level work (at the Command and General Staff College) before having a college degree. That was still possible in his generation — if a man had the talent.

He also had some thankless assignments, but that’s just the ebb and flow of a soldier’s career.

When he was named Distinguished Member of the Regiment (SF’s version of the downmarket Hall of Fame that some other special operations units have) in 2009, it was unfortunately overshadowed by having MOH recipient Col. Ola Lee Mize in his DMOR cohort. Mize earned his Medal the hard way — in Korea, in front of a swarm of screaming Chinese, wielding an entrenching tool when the ammo ran out. Had the other man been anyone but Mize, Aycock would have received the bulk of the news coverage.

He’d have hated that, most probably.

Colonel Aycock shared our highest award, the Combat Infantryman Badge, but he also had a bunch of still higher awards that we do not, like the Legion of Merit, the Presidential Unit Citation (as a personal award, as member of the unit when it earned the ribbon), and Master Military Free Fall wings. He passed on to one final reward that we have not, yet, at approximately 9 AM on the morning of 24 October 2016.

He is survived by a substantial family, many of whom inherited his gene for selfless service. While new greats are always arising, Charles A. Aycock can never be exactly replaced.

Ave atque Vale.

How the Helicopter Seat Came Home

The phone rang and one of the full-timers in the National Guard Special Forces Company picked it up.

“Sergeant Pseudonym speaking, not a secure line.” (There was a long spiel you were supposed to say. It wasted time. We didn’t bother, to the irritation of all the sort of officialdom whose enmity told you you were on target).

“Can you guys destroy two helicopters?”

Can we destroy [fill in the blank]? Is the Pope Catholic? Is water wet? Do Kennedys party hearty? “Sure thing. What’s the deal?”

It turns out an Army Guard unit in our unit’s state (as is common with SF Guard units, most of us individuals were from out of state) had transitioned from flying attack helicopters — obsolete, Vietnam-era UH-1B and AH-1S models — to being a Black Hawk medevac unit. Good mission, and they sure loved the extra power and twin-engine safety of the ‘Hawk, as opposed to the Huey, which was revolutionary in its day, but was a product of the time when cars had tail fins, and putting a turbine engine in a helicopter was a new and dodgy thing.

The commander of the unit had turned in most of the Hueys and Cobras for their smelted future as Hyundai cylinder heads and COSCO screen doors, but he had saved the two most historic craft in his fleet with a view to donating them to an air museum.

The air museum said, “No, not unless you also give us money to restore them.” Well, that the skipper didn’t have. So he tried another air museum.

And another.

And another.

Hueys were either too recent, or too plebeian, and museum curators tend, these days, to be Baby Boomers whose fondest memory of the Vietnam War is how they sent some poor black city kid or hayseed Polack farm boy in their place, so the iconic copters sat at the unit’s old hanagar on an Air Force Reserve base for months that turned into years. The commander with museum ambitions changed out. The Air Base commander who had told him,” leave them as long as you need to,” changed out. The guys that changed out, changed out, as season follows season. The two historic copters were now derelict trash interfering with good order on the Air Base. Not to mention the planned reuse of the hangar as a sort of pavilion with a podium from which the new Wing King could speak enlightenment to his adoring troops, in mandatory attendance. The Air Force Reserve poked the Army National Guard State Headquarters (since renamed Joint Force HQ, and a more wretched hive of scum and villainy, not to mention of well-connected staff officers entering Year 16 of war without a day in 1000-mile proximity to same, there never was). “Get off my lawn,” was the subtext of the message.

In State HQ, the lights went on and unholy things you’d rather not dwell on scattered and scurried. The Fundamental Law of Plumbing applied and you-know-what flowed downhill until the tasking reached some harried Property Book Officer (“Extra duties I don’t want for $500, Alex!”) in the form of an unambiguous command: make those helicopters disappear.

Putting them on eBay was considered, until an outbreak of that persistent plague that rises up and inhibits the human race from truly taking charge of its God-given mastery of the planet.

Yes, lawyers.

The lawyers pointed out that the helicopters must be demilled, that is, rendered unusable and their key parts rendered unusable as weapons of war. Just having engines and avionics out of them — which parts had been cannibalized, or souvenired, we’re not really clear which, in the intervening decade — would not do. They needed to be thoroughly and completely destroyed.

Now, State HQ being the natural habitat of staff officers, hothouse flowers, and power groupies of all kinds, you could look long and hard without finding anyone who had ever destroyed anything more substantial than a subordinate’s part-time Guard “career,” or had any idea how to go about it. So the search began for someone who could destroy something, a talent that is in rather short supply in the upper regions of today’s military.

They found “Company C, XX Special Forces Group” in a phone directory, and someone dimly remembered a movie with John Wayne.

“So, can you guys destroy two helicopters?”

“Yeah, we can do that.”

The question became how to (1) not offend the various Air Base Commanders, Wing Kings, panjandrums, sachems, sagamores and satraps on the Air Base and (2) get the max training value from a couple of helicopters, in such a way that the rotorcraft would be rendered indisputably hors de combat. Everybody’s first choice, “Demo crosstraining!” would certainly have reduced the ships to coin-sized and smaller shards of aircraft aluminum, with all the joy and adventure that comes from having your medics, commo men, and the knuckle-dragging weapons men play with C4, hollow charges, ANFO improvised cratering charges and all kinds of things, usually without bothering with all the ugly arithmetic that the actual demo men have to learn. (“That equation needs more of factor P for Plenty!” FOOM!).

That idea was vetoed by alarmed Air Force officers, and a new requirement was explained: destruction of the rotorcraft had to be environmentally sound.

That meant that Plan B, the big bonfire hot-enough-to-ignite-aluminum in the swamps, pardon, wetlands on the far side of the runway — an area we knew all too well from jumping a tad early on our runway-centric drop zone — was right out, too.

What we came up with was, since medical combat trauma crosstraining was already on the schedule, we’d use the helicopters to stage crash scenes, giving the guys some practice in crash rescue and recovery and casualty evacuation as well as initial treatment in the austere environment.

We hatched an idea with a Chinook outfit to longline the Hueys to a point about 200 feet over the clearing we were given as a training area, and then drop them in. Nothing simulates a helicopter crash like a falling helicopter, right? But that was vetoed by State HQ, with some hurtful words about the unwisdom of letting aviators and SF mission-plan over pitchers of beer. Instead, we had to crash the helicopters using our own resources.

It worked better than expected, although they were kind of sore about the damage to the 5-ton truck (a Huey, it turns out, is stronger than you think).

One of the resources a Special Forces unit does not have is a bunch of privates, and so it’s quite normal for your 5-ton driver to be a bored senior sergeant. And it’s not unheard of for SF guys to take a shine to souvenirs. And if you look around the ranks, you just might find a guy who has an A&P rating and an incredible set of tools in his trunk.

And so it came to pass, when, hours after the exercise was supposed to be entirely secure, with the medical trauma training pronounced a challenge and a success, and even the lawyers thrilled with the shredding of the helicopters incidental to the training evolution, and the green eyeshades of the Finance Corps pleased with the economy of it all, a borrowed 5-ton wrecker dragged in our hors de combat 5-ton cargo truck, complete with a hunk of rotor blade embedded in the brush guard, radiator and fan, and a UH-1B command pilot seat, inexplicably, in the back.

The mechanic cursed his friend, because it was so heavy. We’d guess about 250 lb. It rode the rest of the way home hanging out of the trunk of an old Mustang, into which it did not fit (an attempt to borrow the 5-ton for this purpose was met with unamusement, and pointing out that the 5-ton was paws-up for the next couple of weeks). Then it was horsed up stairs into a Man Cave or War Room, and spent several years there providing a quasi-comfortable seat for reading war books in, before migrating to its current location in the War Room (just inside the Reviewing Our Panzers Balcony, which is really a thing) at Hog Manor. And now, it is promised to an old teammate for his man cave.

Hey, he’s younger. And he, too, was there that day.

Sorry about the truck.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.