Iron sights are obsolete. Britain saw this one, and acted on it, before the United States did. (So did Germany, even earlier; but then they backed off). The plain truth is that iron sights are obsolete, outdated, dead; they’re not just resting or pining for the fjords. They’ve shuffled off their mortal coil and joined the Choir Invisible.

They’re dead, Jim.

As a shooter, you should still understand and be able to use the many kinds of iron sights that have been used on rifles, pistols, and machine guns over the last few centuries. The shooting fundamentals work the same (with the self-evident exception of sight picture and sight alignment) regardless of what kind of sight you’re using, but the iron sight imposes physical, temporal and human factors obstacles that optical sights do not.

The most important of these factors is that an optical sight, whether it’s a traditional telescope, a red-dot, or a holographic sight, puts the aiming point and the target in the same focal plane. How important is this? It’s vital. It reduces the time spent to align the shot (more than compensating for the initial delay imposed by a magnified sight with a limited field of view, it lightens the shooters neurocognitive load, and it reduces hit dispersion downrange.

It’s the nature of a human eye that, unlike a camera, its an extremely complicated piece of hardware that is normally used in pairs to collect a dynamic and changing amount of light that is resolved, not upon the focal plane of a retina, but by the software of a brain resolving, merging and interpolating light data.

Unlike a camera, where the focal plane is just that, a plane, a retina is curved. Unlike a camera, where one pixel receptor of a charge-coupled device (or traditionally, one chemical grain of film coating) resolves the same shades or colors and responds the same to a given amount of light towards the periphery as its companion does at the center, our retinal cells are not all the same. The different kinds, which respond differently to light and color, are distributed unevenly. Unlike a camera, the human visual mechanism with its two eyes, brain, and “software”-driven focus is, at once, a wide-angle lens (with pretty lousy off-axis resolution, but good for movement) and a telephoto (which can perceive great detail, but only straight on).

And unlike a camera, human depth of field is not variable, although the location of focus is. What this means is that you can’t simultaneously focus on the front sight, the rear sight, and the target. Well the most important of those three items is the target, with iron sights you’re likely to miss it if you don’t focus on the front sight. Shooters must be trained (and must practice) to focus on the front sight like that.

So the eye is an awesome piece of engineering (or engineered hardware/software integrated system, really). But it has its limits. In optic land, your aiming point (whether it’s a dot or a crosshair) is superimposed on your target, in a single focal plane. Again, you must train for this, but it takes less training, and it leads to a more rapidly acquired sight.

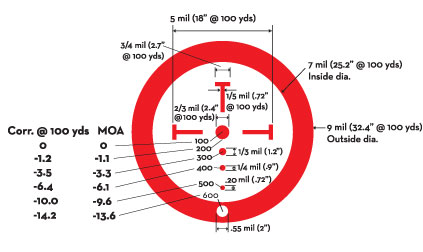

The aiming point can be a crosshair, another reticle, or an illuminated dot. Each has its pros and cons. For rapid training it’s very difficult to beat the red dot. For distance shooting, numerous compensated reticles are available. Some sights try to provide both: any sight with a complicated reticle rewards study, understanding, and practice.

The military forces of the world have been slow in seeing this and issuing optics on a general, wide-scale basis. In fact, it’s taken most of a century for them to catch on worldwide. Before they were able to do so, of course, optics needed to improve: first they needed to be weather-sealed and fog-resistant (first achieved just before WWII), then needed coated optics for improved light transmission, and finally they needed to be ruggedized, or grunt-proofed, if you will. This last is not a small task, as the grunts of any army you could name take a perverse pride in their ability to destroy flimsy gear, and their definition of “flimsy” is eye-opening, if you are not a grunt.

Now, the armies of the world understood the benefits of optics for various artillery, aviation, and even machine-gun uses. (The US issued a dreadful Warner & Swasey telescopic sight for the Benet-Mercié Machine Rifle of 1909; the Imperial Japanese Army had scopes for the Type 92 (1932) medium and Type 96 (1936) light machine guns.

Germany started to do it in World War II, but they lost the war before they could universalize their general-purpose infantry optic, the ZF41. (ZF41, seen here on an FG42, was more common on G.43 and MP/STG.44 type weapons).

After the war, the Federal Republic was slow to adopt optics again, but by the 1960s was issuing a Hensoldt scope to designated marksmen. The current G.36 has its issues, but is optics-ready and issued with a range of optical sights.

Britain, bruised by international opinion, introduced a low-magnification, lighted-reticle optic in 1973, first in Northern Ireland for designated marksmen, then throuhgout the British Army. It never achieved universal issue, but its successor, the SUSAT for the problematical SA.80 rifle, did.

This SUIT (Trilux) sight appears identical to the UK model, but is marked in Hebrew. Gee, wonder who used it?

Meanwhile, in 1977 the Austrian Army adopted the revolutionary Stg.77, known to the world as the AUG (Armee Universal-Gewehr), its trade name. The AUG was a bullpup design with a 1.5 power optic in an M16-like carrying handle, with rude backup sights on top of the scope housing. (Later AUGs used standard, rail-mounted modular optics).

In the 1980s, Canada issued the domestic Elcan C79 as standard on their new rifle, the Diemaco (later Colt Canada) C7, and the C9 general purpose machine gun. The US Army, whose motto in small arms sometimes seems to be “First? Us? Never!” adopted this sight as the M145 Machine Gun Optic (MGO). US SOF drove the adoption of optics in the 1990s, formalizing what had been a lot of single-unit experiments with the circa 2000 SOPMOD initiative. SOPMOD I saw the first version of the Aimpoint M68 and the Trijicon ACOG adopted. (General purpose forces adopted these optics, or improvements on them, very quickly thereafter).

Russian and Chinese forces are seen more and more frequently with optics and with modular sighting equipment.

If you’re still aiming with a peep or open rear sight and a bead or post up front, good for you. It’s great for marksmanship basics. But small arms history is leaving you behind. It’s time to scope out some scopes.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.