A comment by Daniel Watters on our Wednesday post about the Lewis gun made us dig back into that same book, Ordnance and the World War, because we remember Brig. Gen. William Crozier being somewhat defensive about the 1917 Enfield as well.

If you didn’t download it then, here it is: ordnance_and_the_world_war_4.pdf (The digit 4 just refers to our serial attempts to fix the non-searchable nature, bad OCR, and humongous file size of the original, which can be found in Google Books, and also in a different version at Archive.org. It took us several tries to get it right — kind of like World War I gun designers).

A note about terminology: some collectors are snippy about calling the 1917, which was an American sheen on a British-designed rifle of general Mauser action, an “Enfield.” Of all the millions of these “Enfields” made, none were made at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock, England, which was working flat out to make Short Magazine Lee Enfield Mark I and I* rifles for the war, apart from the initial, experimental Pattern 13. With nothing sufficing to make enough rifles for the meat grinders of the Western Front, Dardanelles, and to a lesser extent Middle East fronts, Britain reached out to American manufacturers to modify the Pattern 13, which had been designed for an experimental 7mm rimless cartridge, for the service .303. And they were, in fact, building these rifles when the USA entered the war, having the same problem with its excellent M1903 Springfield rifle — too little production base for the millions needed.

A note about terminology: some collectors are snippy about calling the 1917, which was an American sheen on a British-designed rifle of general Mauser action, an “Enfield.” Of all the millions of these “Enfields” made, none were made at the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock, England, which was working flat out to make Short Magazine Lee Enfield Mark I and I* rifles for the war, apart from the initial, experimental Pattern 13. With nothing sufficing to make enough rifles for the meat grinders of the Western Front, Dardanelles, and to a lesser extent Middle East fronts, Britain reached out to American manufacturers to modify the Pattern 13, which had been designed for an experimental 7mm rimless cartridge, for the service .303. And they were, in fact, building these rifles when the USA entered the war, having the same problem with its excellent M1903 Springfield rifle — too little production base for the millions needed.

We’ll let General Crozier take it from here, for a bit. We pick up on page 56 of his book; and we have added only some paragraph breaks for comfort of the modern reader, and some explanatory interjections.

The most important weapon with which nations go to war is the infantryman’s rifle. This remains a fact notwithstanding the greatly increased impor- tance of artillery, the extensive use of the machine gun, the revival of such early weapons as the hand- grenade and the trench mortar, and the introduction of new ones such as the aeroplane and asphyxiating gas. The rifle was, therefore, a matter of very early concern with the Ordnance Department upon entering into the war, as, indeed, it had been for a considerable time before.

The standard rifle of the American service, popularly known as the Springfield, is believed to have no superior; but our supply was entirely insufficient for the forces which we were going to have to raise. Our manufacturing capacity for the Springfield rifle was also insufficient, and could not be expanded rapidly enough for the emergency. This capacity was available at two arsenals: one at Springfield, Massachusetts, capable of turning out about a thousand rifles per day, and one at Rock Island, Illinois, which could make about five hundred per day. Until September of 1916 the Springfield Armory had been, however, running far below its capacity, and the Rock Island Arsenal, or at least the rifle-making plant, was entirely shut down, due to lack of appropriation.

The money was coming. (The appropriation Crozier mentioned below was also the first real money provided for machine gun procurement, as we’ve already discussed). But physical plant and money, it turns out, are not the only constraints on defense production. Skilled manpower quickly surfaced as a second bottleneck.

At the end of August, 1916, there had been appropriated $5,000,000 for the manufacture of small arms, including rifles. A considerable sum of this appropriation had to be put into pistols, of which we were even shorter than we were of rifles, but the remainder was used to reopen the rifle plant at Rock Island, and to increase the output at Springfield, as rapidly as these effects could be accomplished in the stringent condition of the supply of skilled labor occasioned by the demands of the private factories making rifles for European governments. The dis- sipated force could not be quickly regathered. Fortunately, it had been the policy of the Ordnance Department to keep on hand a considerable reserve of raw material, so that little delay was caused by lack of this important element. We had in April, 1917, about 600,000 Springfield rifles, including those in the hands of troops and in storage; and the ques- tion was as to the best method of rapidly increasing our supply of rifles, of sufficiently good model to justify their procurement.

Note here that Crozier is satisficing, not optimizing; he’s not demanding a rifle the equal of the Springfield (which is a fine example of the genus Mauser, and was more or less forced on the Army after the superiority of Spain’s M1893 7mm Mauser to the US .30 Rifle and Carbine (Krag) was made evident in 1898-99). He just wants rifles of “sufficiently good model”. The logical place to turn is to American industry, where small arms are in production for several European nations. (The US maintained a fig leaf of neutrality by a “cash and carry” policy for arms from 1914-17; we wouldn’t ship them to belligerents in American bottoms, but if you sailed into an American harbor, we’d help you load all the arms you could afford. Getting them home was your problem. This fair-sounding policy actually favored the Allies, because of British sea dominance).

Six manufacturing establishments were making rifles in the United States for foreign governments, and of these, three, the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, of New Haven, Connecticut, the Reming- ton Arms Company of Ilion, New York, and the Remington Arms Company, of Eddystone, Pennsylvania, were making what was known as the Enfield rifle, for the British service.

The British called this rifle the Pattern 1914 or P14 rifle. Yes, the “Eddystone Arsenal” was a Remington plant all along. Two of the other three lines — Remington and New England Westinghouse in Chicopee, Mass. — were making Mosin-Nagant rifles for Imperial Russia, as were plants in France and Switzerland. The third was a Remington production line for French Berthier M1907/15 rifles. If he considered the Mosin or Berthier rifle, he didn’t write about it. (Some so-called Colored units in France would be armed with Berthiers, but they were French-supplied rifles. The Remington order appears to have been rejected by France, as the Mosins were by Russia after the Revolution).

The capacity of these three plants was sufficient for our purpose, and as their contracts with the British Government were running out, and the general type of the rifle which they were making was a good one, it was not difficult to decide that these plants should be used to supplement those at Springfield and Rock Island, which should, of course, be stimulated to their utmost production.

To make the Enfield rifle work in the US Army, it had to be converted to US ammunition, or replace the Springfield and .30-06 round entirely, or, the Army had to live with two incompatible rifle rounds. Crozier really didn’t like that third option.

Certain other questions, however, at once arose. The British type of ammunition, for which the Enfield rifles were being made, was not a very good one, in that the bullet was of low velocity and the cartridges, having a projecting rim at the base, were likely to catch upon one another in feeding from the magazine, and to produce a jam. In addition, this ammunition was not interchangeable with our own, and could not be used in the Springfield rifle. The manufacture, for ourselves, of the Enfield rifle as it was being made would, therefore, have entailed the use of two kinds of ammunition in our service,—and one of these not a very good kind,—or else the abandonment of our Springfield rifle and the complete substitution of the Enfield, with the corresponding throwing out of commission of the Springfield and Rock Island plants and the Government ammunition factory at the Frankford Arsenal.

You see where he’s going with this, right?

There was another difficulty about the Enfield rifle. It was being independently manufactured at the three factories, and there was not only very poor interchangeability of parts in the product of a single factory, but as between the three factories the parts were not interchangeable at all. Under these circumstances, and in view of the moderate supply of Springfields on hand and the manufacturing capacity of the arsenals, it was decided that the new Enfield rifles should be manufactured for use with the United States’ ammunition, and that the manufacture should be standardized so as to effect practical interchangeability of parts throughout.

Here is a period video of M1917 Enfield production. Note the non-trivial amount of hand and eye work here. We’re not sure which of the three plants this is.

It was considered that the Springfield rifle situation justified taking the time required for these changes, of which the first would necessarily appeal strongly to any military man, and the one involving interchangeability could, fortunately, be considered with the aid of an officer who was very familiar with the Enfield rifle as it was being manufactured at the three private factories. This officer was Colonel John T. Thompson, formerly of the Ordnance Department, who had been retired from active service and was in the employ of the Remington Arms Company in connection with their rifle manufacture for the British. I called Colonel Thompson back into active service and placed him in charge of small arms and small arms ammunition, and had the benefit of his expert and especially well-informed advice in deciding that the interchangeability wanted would be worth its cost in time.

Yeah, he’s talking about that Thompson. He goes on to recount some of the abuse he, the Ordnance Department, and the Army took for this decision to modify the M1917, which necessarily delayed its delivery to the front. Here’s a very technical beef with the interchangeability decision from one Senator Chamberlain (Crozier quotes his statement at greater length).

Here were the engineers of these great arms companies, who got together and finally agreed upon a program for the manufacture of these guns, and concluded that they would manufacture them with seven interchangeable parts, and they started to manufacture the gauges, the jigs, and dies, and everything necessary for the manufacture of guns with seven interchangeable parts. After the Ordnance Department had practically accepted the suggestion, it went to work through a distinguished ordnance officer and changed the plan from 7 to 40 interchangeable parts, and finally raised it to over 50 interchangeable parts, with the result that everything had to be stopped for awhile that additional gauges might be made. This may have resulted in improvement, but why the delay in the midst of the smoke of battle?

In fact, the delay was estimated at about 30 days, net over what it would have taken to resume P14 and .303 production. While there was a short period in which soldiers were mobilized before sufficient rifles were on hand, nobody failed to get a modern rifle and train with it before it was time to ship out.

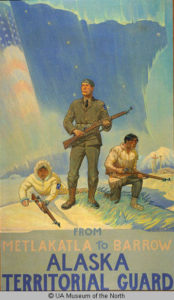

With different lettering, the same poster was used to sell war bonds. Note the M1917s. One man is Eskimo, one white, and one Alaskan Indian.

The M1917 acquitted itself well in combat. Sergeant Alvin York, of the not-airborne-yet 82nd “All American” Division, was one celebrated US Enfield user. The point the critics tried to make was that it could have been on hand sooner. While that may be true, the cost of getting the first Enfields a month earlier would have been a bifurcation of small arms ammunition logistics for the duration of the war. And, of course, the Enfield had a second wind in the Second World War (Alaska Territorial Guard, right).

If there was criticism of the wartime production of the US Rifle M1903, it didn’t rise to a level where Crozier felt he had to address it. And the criticism of his Enfield decisions, while it really stung him (he seems to have been a thin-skinned fellow), was trivial compared to the beating he took over the issue of machine guns and artillery. History ought to record that his decisions on the Enfield were sound and reasonable, and did put first-class rifles in the hands of American doughboys.

The limitations of the defense industrial base forced the United States to use two different infantry rifles in the First World War, but they were both excellent rifles, and were interoperable with respect to ammunition.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

21 thoughts on “General Crozier and the US Rifle, M1917 “Enfield.””

Thanks for digging this out. I’ve downloaded the pdf, thanks for that effort as well, but have only had time to skim it up to now. I’ve got fall break coming up and will try to get it read in that time.

I’m reminded of the old aphorism that history is written by the victors when I read Crozier’s accounts of his decisions. Are you aware of any rebuttals by his peers of his take on things?

Personally, I think he did an adequate job, considering the financial and other constraints undef which he operated from 1914-16.

For the most part, history remembers Crozier via the lens of Lewis’ narrative, which was then parroted by the US press and Congress.

Colvin & Viall’s “US Rifles and Machine Guns” covers the production of the Springfield at the tool and die level. Colvin still felt it was necessary to point out that many of the cuts on the Springfield appeared to be cosmetic and others were needlessly complex and time-consuming.

Note that the Springfield was so labor-intensive to make that the decision to tool up for an entirely different rifle was made rather than to expand the Springfield’s production.

This is the book TRX mentions.

https://archive.org/details/unitedstatesrifl00colvrich

Thanks, added to the E-book pile.

No, they did not turn to a new rifle. The P14 was already in production. They retooled to make the parts interchangeable.

That was very interesting. The model 17 certainly saved the day for our rapidly expanding army at the time and proved equally as good as the 1903. I’ve always wondered why, when WWII came along, the 1903 was front line issue and the model 17 was considered a second line rifle? I’ve shot both and can’t see that difference.

NIH played a large part, from what I’ve read. My only beef with it is the lack of adjustability in the rear sight. The only one I’ve gotten any stick time on is a pretty rough example from the CMP; bore is black, but it shoots just fine, around 3-4 MOA with surplus ammo.

The lack of interchangeability between the different manufacturers didn’t help. You’d only be able to support them via the cannibalization of existing rifles of the same make. You’ll note that the US fixed the issue by dumping much of their M1917 stockpile on desperate allies via Lend-Lease.

The P17’s were frontline rifles in the defense of the Philippines against the Japanese. Around 100,000 were lost there.

Knowing my luck, as a newly minted 2nd Lt of the Army of the United States, I’d get an Enfield and Victory model revolver.

Could be worse. You could get a Chauchat and a Nagant revolver.

I found THIS curious “….was a short period in which soldiers were mobilized before sufficient rifles were on hand, nobody failed to get a modern rifle and train with it before it was time to ship out. ” as the recollection of my maternal Grandfather was (grumbling) “Didn’t even give me a gun till I got to France”. Now he mighta trained on one INCONUS but the best photo we have of him training (since he looks inspection-ready with wrap-puttees and an empty rifle belt) shows him with a German 1888 Commission rifle. I guess one could consider this a “modern rifle” but Grampa didn’t.

He volunteered as a motorcycle courier and carried a 1911 in that role. I think they only had one and so they swapped out – there are several photos where his holster appears empty.

I have a sporterised US rifle of 1917 (built from a bubba’d rifle). It has an original GI barrel. The action locks up like a bank vault. After the sight protection ‘ears’ are removed 7 the rear part of the receiver is properly rounded, it takes scope mounts for a Remington model 30.

The rifle shoots groups right around 1″ consistently. I took me almost a year for the metal work and the stock work but a fine rifle resulted.

Remington kept the same basic action in production for many years as a sporter. A lot of them built for African or Alaskan game, or big lower-48 game like elk and moose.

The Model 30 or 1917 are wonderful actions for dangerous game rifle conversion.

Typical changes are:

1. Remove the “ears” on the rear sight as mentioned above.

2. Forge out the dog-leg in the bolt handle.

3. Modify the bottom metal (magazine) to hold whatever large round you want to shove into the action.

I’ve seen 1917’s modified to accept .505 Gibbs.

The original A-Square rifles were based on the M1917/Remington Model 30.

While I don’t have a great deal of regard for Crozier, either as a man or an officer of ordnance, I must admit his decision on the M1917 was solid.

I regret now I didn’t get a M1917 back when they were available at reasonable prices in the 1990’s.

Last time I checked they normally can be had for less than a 1903.

Which may or may not be a “reasonable” price depending. Seeing A3’s going for 4-5 times what I paid for my first one.

Thanks for reminding me that my new condition M1903A3 of early WWII provenance needs a M1917 for company….