This January, 2010 dash-cam video has been making the rounds by email again (it first went around in April of that year, after a coroner’s jury ruled it a good shoot). It’s worth posting in order to discuss the engagement dynamics.

Hamilton Montana – Police Car Stop Shots Fired – YouTube.

Ross Jessop was a young cop with less than two years on the job at the time. While most commentary in the engagement-dynamics community and in cop-shops everywhere has emphasized the suddenness of the event and the degree to which it took Officer Davis by surprise, the Billings Gazette notes that he knew already that Davis, a man known to be violent when drinking, was drunk; and Jessop was already on edge as he approached the vehicle.

This makes the professionalism in his approach even more impressive. Here’s the Gazette:

On Jan. 1, [Jessop] came on shift at 4:45 p.m. He was scheduled to get off work 10 hours later at 2:45 a.m.

Jessop first saw Davis that night talking to two Hamilton police officers.

The men were questioning Davis about some battery cables that had been cut on his girlfriend’s car earlier that night. Jessop saw Davis shake the officers’ hands and go back inside.

The officers told Jessop that Davis was heavily intoxicated and had been warned not to drive.

Not long afterward, Jessop spotted Davis’ Lincoln Navigator driving north on Second Street. He pulled in behind and followed the vehicle as it turned on Adirondack Street. When Davis used a turn lane to drive straight through the next intersection, Jessop turned on his lights.

Davis crossed the railroad tracks on Fairgrounds Road and pulled over on a patch of dirt almost directly across from the fairgrounds entrance.

Jessop activated his spotlight.

And then the officer saw something that he’d never seen before during a traffic stop. Davis reached out and slowly adjusted his mirror so he could see the officer.

“That’s very unusual,” Jessop testified. “Our spotlights are very bright and they hurt your eyes.”

Most people immediately turn their mirrors so the light is reflected away from their face.

“At that point, I was caught off guard,” he said. “I approached with a little more caution than I usually do.”

Jessop could smell the alcohol on Davis as soon as he neared the window. He asked the man how much he’d drank that night.

“Plenty,” came the reply.

Jessop said the face that stared out the window that night was hard to describe.

“It was argumentative … very sure of himself, almost cocky.”

In the story — do read the whole thing — Davis’s friends describe him as a mean, violent drunk, and say that he’d told two of them that they weren’t going to see him again, and let them know he had the gun. It’s impossible to know what he meant by that; in any event, he was very drunk.

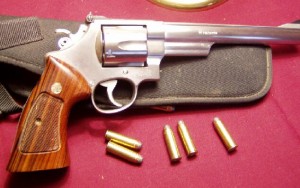

Fortunately for Officer Jessop, Davis was inadvertently playing an inverse game of Russian Roulette — along with five live rounds, Davis’s Smith & Wesson .41 Magnum contained one fired casing. Nobody knows when or where (or at what or at whom) Davis fired the other round, but that empty casing providentially came to be next one up when Davis decided to kill Jessop.

(Aside: a .41 Mag is a pro’s gun, it’s very rare to encounter one in the hands of a criminal. Criminals like guns that are cheap, which the .41 Mag isn’t at all, or guns that have a tough-guy reputation; they’d prefer a .44 Magnum to the more controllable .41. And Davis was a criminal, a repeat violent felon and ex-con who’d done time for assaulting a cop on the Hamilton, Montana police force — the same one that Jessop worked for. Davis couldn’t buy or own a gun legally).

Jessop asked him what he meant by plenty. A split second later the officer was staring down the barrel of a .41 mag-num Smith and Wesson pistol.

“The end looked bigger than a quarter,” Jessop said.

That is, in fact, a common psychological effect of having a gun pointed at you at close range. A .41 looks quarter-size; a shotgun looks like an M-79.

Jessop heard a click.

Davis pulled the trigger and the hammer fell on an empty round.

That click is audible on the YouTube video, immediately before Officer Ross Jessop says a naughty word — for which he may reasonably be excused.

“My very first thought … after I realized it was a revolver was I was terrified. Absolutely terrified,” Jessop testified. “I recall thinking I wasn’t going to see my wife again. I wasn’t going to see my mom, my brothers, or my sisters, or my coworkers or my dogs. I was terrified.”

Jessop moved his face away from the threat as fast as he could.

“I did hear the click,” he said. “I remember stopping. I was actually hoping it was just a joke … I remember thinking why would you do that to an officer?”

And then he saw Davis’ head readjust.

“I remember thinking the reason he’s readjusting his head is he’s going to shoot again,” Jessop said.

He ran toward the back of Davis’ vehicle, while drawing his Glock, Model 22.

This displacement was an excellent move. It complicated Davis’s target solution, which Davis fortunately was not able to mentally resolve well enough to score a hit on Jessop. It helped Jessop that Davis’s mind was clouded by alcohol. One is reminded of the old Irish joke: “Sure and Uncle Denny took a shot at one o’ the Black an’ Tans, but th’ curse of th’ dhrink was upon him, and he missed.” But let’s return to Ross Jessop’s testimony.

He heard a gunshot.

“My next thought was I had to defend myself and eliminate the threat to me,” Jessop said. “I don’t recall drawing my weapon. I do remember my first shot. I was conscious that I was shooting my gun.”

Jessop thought he’d fired seven or eight rounds. It turned out he’d fired 14.

What we’re seeing here is “reversion to training” — a man under intense, existential psychological stress, operating at the level of muscle memory without his higher-brain functions even being engaged, and therefore not forming memories of specific acts that were so drilled that they were, literally, instinctual.

Six bullets hit Davis’ vehicle, including the one that drove through the passenger and driver’s seats and into Davis’ back.

About average for a police shooting these days. Combat is extremely stressful and enervating, and the complex processes of marksmanship suffer.

After Davis’ vehicle stuck the power company’s building and came to a stop, Jessop loaded his rifle and got in his car and moved closer.

Ravalli County Attorney George Corn asked him why after he’d just been nearly killed did he move closer to his assailant.

“My duty as an officer is to make sure the community is safe,” Jessop said. “I had no idea if I hit him or not. My thought was to get close enough to keep the area safe and keep myself safe.”

Watch the video again with Officer Jessop’s thoughts, above, in your mind.

Some armchair critics have criticized Jessop’s conduct in this shooting. We see a lot less to criticize. Here’s the Weaponsman bullet-point analysis.

- He remained professionally courteous right up until a gun is in his face. Then he reacts, and says a naughty word, for which any sentient being will excuse him.

- What you see Davis’s stainless-steel hogleg shoved in Jessop’s face, understand that from this point on what’s happening, mostly, is Jessop reverting to his training. This is the point of modern stress-inoculation training: the guy makes a faster-than-the-speed-of-thoughr transition from merely alert to rapidly and effectively responding.

- Saved by the deus ex machina of the empty casing, he ran out of the KZ to a safer place, increasing the distance, moving to a position that provided some minimal cover and concealment and that gave Davis a difficult shooting angle, and providing a nonstationary target. All of these greatly complicate the target solution for the criminal shooter. Even in the hands of a sober assailant, a handgun is an imperfect tool that will conspire with conditions to produce many misses under combat stress. Anything you can do that makes it harder for him is a good thing.

- Some have criticized Jessop for shooting from behind, and for continuing to shoot as Davis drove off. Those critics are fools. Once the drunken suspect began to shoot, the reasonable thing to expect the officer to do is to continue to engage Davis until Davis’s threat was eliminated.

- As soon as possible Officer Jessop holstered his sidearm and rearmed himself with a more effective rifle. Never take an open hand to a knife fight, a knife to a gun fight, a gun to a rifle fight, or a rifle to an artillery fight. Only in Hollywood do you tool down to the opponent’s level and have a fair fight. Out in the real world, you want to make that fight as unfair as you possibly can.

The jury took one hour to rule the shooting justified. That one hour is a group of good people facing the simplest of decisions, providing a decent interval to signal that they took their duty seriously.

Some policemen will watch this video and conclude that, since any meeting with the public can go from “license and registration, please” to gunplay without warning, the right answer is to treat every ticket-writing opportunity as a felony stop, or to scream and yell and threaten your way through your shift in order to make it back home safely. in our opinion, that’s the wrong message. Ross Jessop approached his suspect as, to steal a Special Forces buzz phrase, “a quiet professional.” It is likely that in thirty more years of carrying a badge, he’ll never again encounter a human malignancy like Davis again. If he can maintain a vigilant state and the same quiet professional demeanor he used to approach Davis, he’ll leave a reservoir of goodwill for the police, which benefits forces and individual officers in myriad ways.

We’re not saying it’s easy. The nature of a cop’s job means that you’re not encountering nature’s natural noblemen at the pinnacle of their humanitarian luminosity, most of the time.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

3 thoughts on “Engagement Dynamics of a Police Gunfight”

Quite impressive. His community is fortunate to have a steady professional like that protecting them.

You had mentioned there was criticism of the policeman’s actions. I would say this to the critics, “What’s right is right What’s wrong is what gets you killed.” Obviously he survived and did his job. This video taught me a lot. It re-enforces why awareness is so vital to what I do and this gentlemen does. I’m glad he made it home.

Yes, Joe, we got a very detailed critique from a former LA Sheriffs’ Office deputy that I meant to work into a post. Bottom line was: with someone acting this flaky, where you know of his issues (remember the shooter was well known to cops and they knew he was drunk and suspected he was armed), he’d rather sit tight and wait for backup. He did agree that the cop’s instincts were good once the shooting started. I come from a military background; I’ve ridden with cops and trained cops, but that’s not the same as being a cop. And so I don’t always see things experienced cops see. As it was, the cop went home and the bad guy went to the icebox without taking anyone (officer or member of the public) with him.