Such was a British headline a century ago. after Germany released poison gas on French Algerian troops in May, 1915. But the Hun actually introduced posion gas into warfare 100 years ago today, making today the centenary of WMD.

The BBC has an interesting article with some of the history, as well as some interesting observations on the effectiveness of gas weapons in the Great War. That first introduction on 31 January 1915 was a disappointment to its Trutonic authors, says the Beeb:

As he climbed to the top of the church belfry in Bolimow, west of Warsaw, General Max Hoffman of Germany’s Ninth Army was expecting a bird’s-eye view of a military breakthrough – and a new chapter in warfare.

The date was 31 January 1915, and he was about to witness the first major gas attack in history.

Gen Hoffman watched as 18,000 gas shells rained down on the Russian lines, each one filled with the chemical xylyl bromide, an early form of tear gas. But the results left him disappointed.

“I had expected much greater results from the employment of this ammunition in – as we then imagined – such large quantities. That the chief effect of the gas was destroyed by great cold was not known at that time.”

But the failure at Bolimow proved to be only a temporary setback.

By April, German chemists had tested a method of releasing chlorine gas from pressurised cylinders and thousands of French Algerian troops were smothered in a ghostly green cloud of chlorine at the second Battle of Ypres. With no protection, many died from the agonies of suffocation.

via BBC News – How deadly was the poison gas of WW1?.

The actual effect of the gas was much less than its large presence in the public consciousness of World War I would indicated:

Casualty figures do seem on the face of it, to back up the idea that gas was less deadly than the soldiers’ fear of it might suggest.

The total number of British and Empire war deaths caused by gas, according to the Imperial War Museum, was about 6,000 – less than a third of the fatalities suffered by the British on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916. Of the 90,000 soldiers killed by gas on all sides, more than half were Russian, many of whom may not even have been equipped with masks.

Far more soldiers were injured. Some 185,000 British and Empire service personnel were classed as gas casualties – 175,000 of those in the last two years of the war as mustard gas came into use. The overwhelming majority though went on to make good recoveries.

According to the Imperial War Museum, of the roughly 600,000 disability pensions still being paid to British servicemen by 1929, only 1% were being given to those classed as victims of gas.

“There’s also an element of gas not showing itself to be decisive, so it’s easier to… not have to worry about the expense of training and protection against it – it’s just easier if people agree to ban it,” says Ian Kikuchi.

In the end, gas was a psychological weapon, but with war gases and gas-countermeasures such as masks and suits equally available to all sides, the prospect of a decisive employment of gas was unlikely. That makes it a little clearer why postwar conventions banned gases.

Gas After the Great War

Gas research continued, and the Germans made numerous interwar breakthroughs, which then inspired British breakthroughs (producing the nerve gases, G- and V-agents respectively). But Germany never used gas in World War II, perhaps because of Hitler’s experience being gassed at the Front in the First War, perhaps out of fear that the Allies had equaled German research (they hadn’t, until very late). Russia never renounced the use of gas, and used it postwar in various peripheral conflicts (as well as supplying it to numerous client states), but never used it in the Great Patriotic War. Russians, as the Beeb noted, suffered more than anyone from the gas warfare of the First World War.

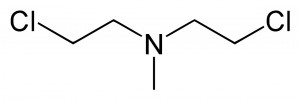

In World War I, every nation tried to be the one that used a new gas first. In World War II, every nation held its war gases back, to retaliate if someone else did — and no one did. The most serious gas casualties of World War II resulted from an American stockpile aboard ship in the harbor of Bari, Italy, being inadvertently released by a German Ju88 night bomber attack on shipping in the harbor on the night of 2 December 43. One of the 16 sunken ships contained 100 tons of nitrogen mustard, HN (methyl-bis(beta-chloroethyl)amine hydrochloride). The HN was reportedly not in bulk storage, but loaded into M47 series chemical bombs:

Most of the HN burned off, but the part that mixed with bunker oil in the water injured 617-628 men (numbers in sources vary), of whom 83 subsequently died. Ironically, because of HN’s effect on lymph nodes and leukocytes, follow-on studies on the Bari bombing survivors were helpful in developing chemotherapy for leukemia, Hodgkin’s Disease, and other lymphomas.

War gases (mostly nerve and blood agents) were a critical part of Warsaw Pact and Soviet war plans, and were used widely in Soviet proxy wars, mostly against civilians. The US developed safe-handling binary chemical munitions as a counterweight, but has since destroyed its chemical stockpiles and production capacity.

We’ve come a long way from the Kaisers 1914 “Devilry.”

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

10 thoughts on “Devilry, Thy Name is Germany”

Technically, the US still has a small portion of its stockpile. Pueblo Chemical Depot (Pueblo, CO) has 2,500+ tons of mustard agent, mainly in artillery shells. Blue Grass Army Depot (Richmond, KY) has 500+ total tons of H mustard agent and GB and VX nerve agents in a combination of artillery shells and unguided rockets. Both facilities are in the process of building destruction plants and their inventories should be gone by the early 2020s.

Most of the mustard is no longer viable for its intended use because it dates to the 1940s and the liquid contents have partially solidified like an expired jar of Grey Poupon. The nerve agents are still potent.

Cool, when I worked in WMD defense I was on the bio side and I recall the chem destruction programs always being a political football locally.

When you drive around certain facilities, you still see the markings on the buildings. I suspect you know what I mean.

There’s a destruction facility in Maryland that was built for stuff there. For the general readers, they aren’t cool with putting this stuff on trucks and trains any more, so they try to destroy it close to where it’s stored.

The US renounced offensive use of bio and first use of chem in 1970, but no first use of chem was always US policy after WWI. Since 1970, all us bio research has been defensive in nature, and it’s very necessary, as five or six nations maintain an offensive capability or research to support one.

There’s also the occasional dump (literally) of shells that turns up interred at a range facility. About 10 years ago they found WWI vintage chem artillery and mortar rounds that had been buried in WWII at Anniston Army Depot, IIRC, or somewhere in Alabammy, anyway. That was how they closed warehouses out until 1943 or 44 or so. So there’s possibly a few more instances of that practice, still out there somewhere.

Does anyone have an idea of how effective Warsaw Pact deployment of chemicL weapons would have been? I seem to recall reading in some alternative history novel, either Red Storm Rising or Team Yankee probably, that they would not be very effective, really just a nuisance. With Russia on the march again, maybe those novels are relevant again.

I think WWI tells the story, mostly. Very effective against unprepared troops, and a minor pain in the ass against prepared ones. The US mil in the 1980s was well prepared. In 10th Group we jump-tested several mask designs. I never figured out if the US M17 (standard at the time, we were testing large-faceplate replacements) was a copy of the Czechoslovak M10 (I think that’s the nom) or the other way around. Bad for rifle shooting, but good masks in general.

We expected Ivan to hit things like airfields with nonpersistent blood agents (high lethality, quick dispersal) and follow up with landings, and to hit things like logistics centers with persistent nerve and blister agents to force the loggies to stay masked and work slowly.

Thank you for the response. I would to read more about your Cold War dealings.

You have a May 1914 and a 31 January 1914 that look out of place. Should they both be 1915?

Thanks, Simon. Start of year error, like I make in my checkbook. Fixed, thanks.

where can I read (preferably online) about Soviet use of chemical weapons in post-WW2 period?

thanks

The only place I know Soviet forces used them directly is Afghanistan. The Soviets also used to provide them to their allies, which is how such worthies as Assad, Gaddhafi and Hussein got them, not to mention Cambodian state agencies.

Here’s a declassified TS summary from 1982. The deletions mostly refer to intelligence sources and methods, although some are mentioned. Only in Afghanistan did the USSR use the chemical weapons directly; in other nations they supplied them, and the know-how to use them, to locals.

http://www.foia.cia.gov/sites/default/files/document_conversions/89801/DOC_0000284013.pdf

Here’s a follow-up. By this point we had samples of toxins and chemical weapons from Afghanistan (see Annex 1):

http://www.foia.cia.gov/sites/default/files/document_conversions/89801/DOC_0000273395.pdf

Why did they do it (one year follow-up):

http://www.foia.cia.gov/sites/default/files/document_conversions/89801/DOC_0000284024.pdf

Here is a more recent academic report laying out evidence against the Yellow Rain aspects of the US’s 1980s analysis. Note that it does not alter reporting on agents such as tabun or phosgene oxime, which were also used in Afghanistan:

http://cns.miis.edu/npr/pdfs/81tucker.pdf

All I will say about that is that Harvard biologist Matthew Meselson’s neutrality in issues regarding the US vs. the USSR is, to put it mildly, disputed in the US intelligence community. But his case for the USSR is laid out fairly in that paper.

I think that the USSR decentralized chemical (& bio & nuke, too) weapons release a lot more than its western opponents did. These things could have been done by some Colonel, and maybe not even a Russian or Soviet one (there’s thin evidence for pro-Soviet Afghan government use of CW against rebeles even before the Soviets arrived to keep the rebels from winning).

We NATO WMD Powers (US & UK) restricted nuclear and chemical exactly weapons alike, and they required National Command Authority permissive action link release. (I do not believe that France ever pursued an offensive chemical or bio program after WWII, by the way, or even much research). That, and the fact that the US and UK did not provide these weapons to our allies, helped to reduce our accidents and problems with the stuff. We had a bio testing accident that killed sheep in Utah; Biopreparat had accidents that killed a bunch of citizens of Sverdlovsk. There was probably a luck factor in that: ours was good, your guys’ was bad.

Chemical weapons are more useful as area denial and to impede military operations by forcing everyone into MOPP than actual killing/wounding power. Operating an Artillery battery, cooking chow and other sundry task become more tedious and slow.

Actual best use is on unprepared and un protected troops and civilian’s.

It serves mostly to piss your enemy off and make reprisals a certainty.