If you take that question the wrong way, you’re thinking who is this bozo to diss Saint JMB? But we’re not putting the emphasis on the JMB side of the sentence, but the What’s so special? end. As in: we really want to know. Why is this guy head and shoulders above the other great designers of weapons history? What made him tick? What made him that way?

Browning was not a degreed engineer, but he is, to date, the greatest firearms designer who has ever lived. Consider this: had Browning done nothing but the 1911, he’d have a place in the top rank of gun designers, ever. But that’s not all he did, by any means. If he had done nothing but the M1917 and M1919 machine guns, he’d have a place in the top ranks of designers. If he’d done nothing but the M2HB, a gun which will still be in widespread infantry service a century after its introduction, and its .50 siblings, he’d be hailed as a genius. One runs out of superlatives describing Browning’s career, with at least 80 firearms designed, almost 150 patents granted, and literally three-quarters of US sporting arms production in the year 1900 being Browning designs — before his successes with automatic guns.

He did all that and he was just getting warmed up. He didn’t live to see World War II, but if he had, he’d have seen Browning designs serving every power on both sides of the war. If an American went to war in a rifle platoon, a Sherman tank, a P-39 or P-51 or B-17, he and his unit were gunned-up by Browning. If he made it home to go hunting the season after V-J day, there were long odds that he carried a Browning-designed rifle of shotgun, even if the name on it was Remington or Winchester. Browning’s versatility was legendary: he designed .25 caliber (6.35mm) pocket pistols and 37mm aircraft and AA cannon, and literally everything in between. He frequently designed the gun and the cartridge it fired.

A lot of geniuses have designed a lot of really great guns since some enterprising Chinese fellow whose name is lost to history discovered that gunpowder and a tube closed at one end sure beats the human hand when it comes to throwing things at one’s enemies. But nobody comes close to Browning’s level of achievement; nobody matches him in versatility.

So why him? As we put it, what’s so special?

We think Browning’s incredible primacy resulted from several things, apart from his own innate talent and work ethic (both of which were prodigious). Those things are:

- He was born to the trade

- He was prolific: his output was prodigious

- He was a master of the toolroom

- He lived at just the right time

- He could inspire and lead others

Born to the Trade

John M’s father, Jonathan Browning, was, himself, a gunsmith, designer and inventor. He made his first rifle at age 13, and despite being an apprentice blacksmith, became a specialist in guns by the time he was an adult. From 1824 he had his own gunshop and smithy in Brushy Fork, Tennessee, and later would move to Illinois (Where he befriended a country lawyer named Lincoln). He joined the Mormons in Illinois and fled with them to Utah, making guns at each way station of the Mormon flight.

Jonathan Browning Cylinder Repeater. Image from a great article on Jonathan Browning by William C. Montgomery.

Very few of Jonathan’s rifles are known to have survived, but he made two percussion repeating rifles that were, then (1820s-1842), on the cutting edge of technology. The Slide Bar Repeating Rifle was Jonathan’s term for what is more widely called a Harmonica Gun. The gun has a slot into which a steel Slide Bar is fitted. The slide bar had, normally, five chambers; after firing a shot, the user cocked the hammer and moved the Slide Bar to the side to move the empty chamber out from under the hammer, and a loaded chamber into place. When all five chambers had been discharged, the Slide Bar was removed, and each chamber loaded from the muzzle and reprimed with a percussion cap. Jonathan Browning’s gun differed from most in that it had an underhammer, and that an action lever cammed the Slide Bar hard against the barrel to make a gas seal. He also made a larger Slide Bar available — one with 25 chambers, arguably the first high-capacity magazine.

The second Browning innovation was the Cylinder Repeating rifle. This was a revolver rifle, with the cylinder rotated by hand between shots. Like the Slide Bar gun, the cylinder was cammed against the barrel to achieve a gas seal — the parts were designed to mate in the manner of nested cones.

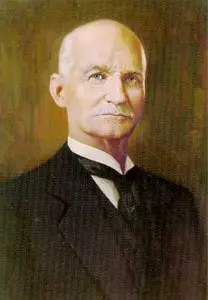

Young John M. Browning. From the Browning Collectors web page.

The designer of those mid-19th-Century attempts to harness firepower sired many children; like other early Mormons, he was a polygamist, and his three wives would bear him 22 children. From age six one of them apprenticed himself, as it were, to his father. Within a year he’d built his own first rifle. This son was, of course, John Moses Browning.

(Aside: the last gun made by Jonathan Browning was an example of his son’s 1878 single-shot high-powered rifle design, which would be produced in quantity by Winchester starting in 1883).

Malcolm Gladwell has popularized the idea that it takes 10,000 hours of hard work to become an expert — that’s roughly five years of fulltime labor. JMB had exceeded this point before puberty.

If you aspire to breaking Browning’s records as a gun designer, you need to acknowledge that, unless you started from childhood, you’re starting out behind already.

Prolific Output

Browning worked on pistols, rifles, and machine guns. He worked on single-shot, lever, slide, and semi-automatic actions, and his semi-autos included gas-operated, recoil-operated, direct-blowback, and several types of locking mechanism. Exactly how many designs he did may not have been calculated anywhere: it’s known he designed 44 rifles and 13 shotguns for Winchester alone, a large number of which were not produced, and some of which may not have been made even as prototypes or models.

His military weapons included light and heavy infantry machine guns, aerial machineguns for fixed and flexible installations, and several iterations of the 37mm aircraft and anti-aircraft cannon, the last of which, the M9, would fire a 1-lb-plus armor-piercing shell at 3000 feet per second; an airplane was designed around it (the P39 Airacobra, marginal in US service but well-used, and well-loved, by the Soviets who received many via lend-lease). All the machine guns used by the US from squad on up in WWII and Korea were Browning designs. But these were only his most successful designs; there were others. At his peak, he may have been producing new designs at a rate of one a week.

If you want to to be the next John Browning, you need to start designing now, and keep improving your designs and designing new ones until the day you die. (Browning died in his office in Belgium).

Master of the Toolroom

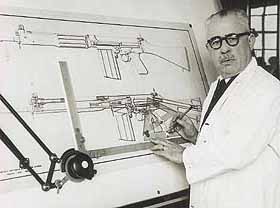

From an early age, John learned to cut, form and shape steel. This is something common to most of the gunsmiths and designers of the early and mid-20th Century — if you remember our recent feature on John Garand, the photo showed him not a a drawing board by at a milling machine.

Browning could not only design and test his own prototypes — he could also design and improve the machinery on which they’d be produced, a necessary task for the designer in his day. Nowadays, such production development is the milieu of specialized production engineers, who have more classroom training, and probably less shop-floor savvy, than Browning brought to the task.

A reproduction of Browning’s workshop in the Browning Museum in Ogden, UT. (From this guy’s tour post).

In Browning’s day, processes were a little closer to hand-tooled prototype work, but it still required different kinds of savvy and modes of thinking .

If you want to be Browning, you have to master production processes, for prototypes and in series manufacturing, from the hands-on as well as the drawing-board angle. There may never again be a designer like that.

Living and Timing

John M. Browning in 1921 with Mr Burton of Winchester and the category-creating Browning Automatic Rifle.

John M Browning lived in just the right time: he was there at the early days of cartridge arms, when even basic principles hadn’t yet been settled and the possibilities of design were wide-open and unconstrained by prior art and customer expectation. No army worldwide, and no hunter or policeman, really had a satisfactory semi-auto or automatic weapon yet (except for the excellent Maxim)

It’s much easier to push your design into an unfulfilled requirement than it is to displace something a customer is already more or less comfortable with.

If you’re going to retire some of John M. Browning’s records, you’re going to need the right conditions and a few lucky breaks — just like he had.

Inspiration and Leadership

To read the comments of other Browning associates of the period is to see the wake of a man who was remarkable for far more than his raw genius. Browning was admired and respected, to be sure, but he was also liked. At FN in Belgium, the gunsmiths called him le maître, “the master,” and took pleasure in learning from him.

His Belgian protégé, M. Dieudonne Saive, went on to be a designer of some note himself. While he did not achieve Browning’s range of designs, he, too, is in the top rank for his work finalizing the High-Power pistol (also known as the GP or HP-35) that Browning began, and for his own SAFN-49 and FAL rifle designs, and MAG machine-gun, all of which owed something to Browning’s work as well as Saive’s own.

If you want to be the next John Moses Browning, you have to know when to step back, and how to share the burden — and the credit.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

4 thoughts on “What’s so special about John Moses Browning?”

EMC

Great summary of a great man. I happen to come through David Browning, John’s brother who worked in the family shop in Ogden as a gunsmith. I like to think that my interest in tinkering with firearms has some genetic link. The Ogden museum is a fun place to visit.

What your post points out, and a lot of people don’t grok, is that Browning not only designed firearms, he designed whole categories of firearms.

In the fields of, say, repeating shotguns or self-loading pistols, they were designing around Browning’s patents for decades.

JMB is responsible for millions of lives being saved. A firearms designer as humanitarian? You better believe it.

First things first. there was no. such. thing. as an engineering degree 120 years ago. He couldn’t have been a ” degreed engineer” even if he had wanted. In that day and age one became an engineer by “doing” engineer things. He was a genius. A remarkable man who designed firearms like crazy and who was not quite, but nearly 100 years ahead of his time. As a mechanical designer I have trouble even benchmarking his machining processes, let alone recreating them. He was a truly remarkable man. You would do well to emalate his processes and work ethic.