The word most used describing Back to 1942 is “epic,” and that it surely is. Its entertainment value is limited, though, by the sheer misery of the tale it tells, a tale of grinding, unrelieved suffering. It is a Chinese film with a predominantly Chinese cast; western actors like Adrien Brody and Tim Robbins are cast in supporting roles. The film is mainly shot in Chinese, with foreigners’ parts in Japanese and (often accented) English. Everything’s fortunately subtitled.

The word most used describing Back to 1942 is “epic,” and that it surely is. Its entertainment value is limited, though, by the sheer misery of the tale it tells, a tale of grinding, unrelieved suffering. It is a Chinese film with a predominantly Chinese cast; western actors like Adrien Brody and Tim Robbins are cast in supporting roles. The film is mainly shot in Chinese, with foreigners’ parts in Japanese and (often accented) English. Everything’s fortunately subtitled.

It tells the story of the events of the war in Hunan Province in the captioned year. Hunan is a breadbasket province and one of the ur-sources of the Chinese festival cuisine loved worldwide, thanks to the Chinese restaurant diaspora. But in 1942, drought, war, and central planning by the Kuomintang (nationalist) government harvested a whirlwind of crop failure, misallocation, and privation. Three million Chinese starved to death; untold millions were dislocated. Neighboring Shansi Province, traditionally the succor of disaster-struck Hunan, had its own woes and turned its neighbors away. The Japanese had a brilliant stroke of UW thinking, and began to feed the starving refugees, co-opting them as laborers. For the average Chinese peasant or smallholder, life then was as near to Bronze Age slavery as makes no difference.

Back to 1942 is unsparing in its evocation of this bleak time in Chinese history. It is hard to sit and watch. In fact, we metered it out over three nights, in part because it uses a cat as a plot device and we have just lost a cat — our suffering, and our cat’s probable end at the teeth and claws of a fisher, don’t compare in any way to the miseries brilliant director Feng Xiaogang metes out to his characters (not to mention what looks like tens of thousands of expendable, and expended, extras), but the little guy’s absence did not leave us in the right frame of mind for this exercise in cinematic masochism.

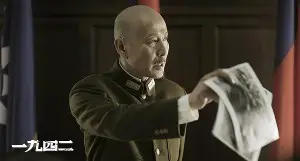

In part, perhaps, this tale is meant to tarnish the escutcheon of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, the wartime Chinese leader and postwar rival to Mao, and his Kuomintang government. But any such intention is undermined by the excellent performance by Chen Daoming as Chiang. He fully gets across that this is a man who must be publicly confident whatever his private feelings. Chen is clearly capable of great things, and we’d like to see more of him.

The story tells several interlocking plots of Chinese people at every level of society and status; it’s reminiscent of a Russian novel, or one of James Michener’s later works, that way. The central story is that of a small landholder (Master Fan) and his family, young daughter Xingxing, pregnant daughter-in-law Huazhi, and loyal, if dim, servant Shuanzhu. But we also follow a traveling judge whose court rolls in an oxcart and whose authority comes in the form of two soldiers; a Chinese priest who confesses to his expat bishop a complete loss of faith; Chiang himself and his advisors, who have to select their war decisions from a menu of bad options; and the melancholy Governor of Hunan. Brody has a solid supporting role as American Communist newsman Theodore White. Brody is a fine actor, probably best known to American audiences for his brilliant performance in the gripping The Pianist (which we can’t recommend only because its director is a kiddie diddler. If you can separate that out in your mind or moral system, it’s a great film).

In the course of the movie, one disaster after another quite believably cascades down on the long-suffering shoulders of Fan and his clan. For them it is TEOTWAWKI; they lose their wealth and position, their health, and one after another, their lives or liberty. It almost doesn’t matter if the disaster is natural, man-made by depersonalized Japanese war machines, or man-made by China’s own corrupt warlords or routed, fleeing soldiers. When those disasters are not horror enough, the characters are given choices, but only between greater evil and evil still greater yet. It’s just one disaster after another.

There is a miracle of survival, but not for everyone and not without terrible cost.

Acting and Production

The acting is excellent. We’ve already mentioned some of the actors, but Zhang Guoli’s Master Fan is an incredible performance, stoic in the face of unimaginable horrors. Zhang Hanyu has a powerhouse role, too, as Father SImeon, the Chinese priest whose originally solid faith can’t bear up under the weight of privation and human depravity. A Japanese attack on a refugee column is the last straw, and Simeon asks the question theologians ever struggle with: “Why does God let this happen?” Robbins as his superior responds that what Simeon has seen is not the work of God, but of Satan. At the end of the scene, Simeon’s faith is not restored one bit. Zhang’s performance as Simeon is so strong, you scarcely notice Robbins’s lines.

The production is epic, also. As we mentioned, it’s reminiscent of a Russian novel, and some of Feng’s long camera shots and other cinematographical effects are reminiscent of two movies with Russian themes, the excellent Dr. Zhivago and the dreadful Reds. Feng seems to enjoy juxtaposing beauty — the classical landscaping of China’s leaders’ gardens, for instance — with repulsive ugliness. But as the film shuffles on, the ugliness gets uglier and more front and center.

Accuracy and Weapons

If you’re reading this, you want to know about the arms. While it’s a film set in war, it’s not a war film per se; despite that, the producers clearly worked like dogs to ensure the military hardware depicted was accurate, whether they were using original or repro equipment, cosmetic replicas, or CGI.

The small arms are correct for time and place: the various Chinese Mauser types, including lend-lease Springfields, and the right machine guns — ZB26, MG08 — are there. The Japanese have Japanese rifles. Many Chinese carry Broomhandles, and one shows up on the church doorstep with an early Nambu, either a Small Guard Type 14 or a Papa Nambu (it wasn’t clear enough, and we’re not Nambu-savvy enough, to be sure).

When guns are fired, in most cases there are realistic sights and sounds. One execution scene, in which Chiang’s men make an example of some profiteers, shows some unusual, probably CGI, muzzle-to-target effects. It’s probably explained as cinematic license.

Guns can be central to a scene without a shot being fired. The ox-cart court (ox-court?) at one time has Shenzhou in its grip, for possession of a firearm, and intends to give him up to the Army as a draftee. Nothing about this film’s depiction of the Chinese Army makes enlistment look desirable. In the end, the loyal servant is sprung by Master Fan paying a bribe, in what has become the currency of starving Hunan: cups of millet. The bribe is sufficient to save the servant, but not the gun; which is good enough, one thinks, because against the human, national, and celestial forces arrayed against our heroes, one Mauser isn’t going to cut it.

The powerless of an individual with a gun on this vast Bosch canvas of Hades is hammered home when a frustrated Theodore White (Brody) abandons his photographic efforts amid the chaos of a Japanese air attack, and blazes away at the Japanese planes. It is the .45 scene from Patton, but it isn’t; in Patton, George C. Scott played the scene with heroism, even an eerie fearlessness. Indeed, he hits the German plane. But here, Brody is not firing in anger and determination. It is not a heroic act, but a desperate one. He is firing at the Japanese out of frustration and impotence. He has no expectation of striking a plane, and he doesn’t, he’s just expressing futile, inchoate rage.

This is not to say that the movie is “anti-gun” (or “pro” for that matter). It exists in a world apart from such American political concepts. In Back to 1942, guns just are, and they’re just one more externality that usually brings tragedy and suffering into the lives of ordinary people.

So the guns are realistic, if somewhat orthogonal to the story. Aerial attacks (all delivered by the Japanese) are more problematical. The Japanese aircraft are, of necessity, CGI (very few survived the war, none at all of many important types), and in their sleek perfection they contrast markedly with the ox- and human-drawn carts of the Chinese refugees in their bombsights. The static renderings of the airplanes were done with great care, they’re lovely work; but their motion in the air is phony and unrealistic, and the fall of bombs and shot is grossly out of whack. The aircraft are not shown reacting to wind or one another’s wake, and they’re at patently different altitudes from inside shots to outside views and back again. They’re not depicted in any tactically sensible manner: level bombers attack from 100 feet AGL, using a sophisticated drift bombsight. What all that adds up to is that the plane CGI and the scenes involving it look fake, even dated (They’re reminiscent of the bad CGI in 20-year-old Hollywood fare, like Die Hard 2: Die Harder. That’s not what a director of Feng’s vision or talent should be seeking for a comparison). Don’t fire the CGI guys, get them more exposed to the things they’re modeling.

Vehicles and armor are shown, however they did it (the DVD has no making-of featurette) in generally accurate types and behavior. The Chinese have lend-lease Jeeps and trucks; the Japanese vehicles, including Vickers-like light tanks, seem accurate, mostly. A few times they substitute a later military vehicle (like a GAZ 69) that’s an anachronism if you’re a truck nerd. But this movie mostly takes place on foot (and at a burdened pedestrian’s pace too).

The bottom line

Back to 1942 is 2 1/2 hours of miserable suffering on-screen. Your heart goes out to compelling characters, only for them to be as doomed, in the end, as Master Fan’s innocent daughter Xingxing’s cat. (Trust us, not entirely a spoiler. If you know there’s a famine on, and you know — or will quickly learn from Back to 1942 — that Feng is a strong adherent of the principle of Chekhov’s Gun, don’t show it in act one if it won’t be “fired” in act three — you know that a beloved kitty’s on-screen destiny is a question of when, perhaps how, but never what).

You will learn something of Chinese history, assuming that Feng’s care with the details is matched by care with the setting — we don’t know enough to say. But the movie was, for us, depressing. It was a huge success in China, but not here; along with subtitle-phobia, US audiences are perhaps too conditioned to films that follow a Blake Snyder formula. The late script doctor Snyder advised screenwriters to use a “beat sheet” and at certain predictable run-time points to raise the odds and deliver defeats and setbacks to his characters, so that their final triumph delights the audience. Feng does that, except that the defeats and setbacks just lead to more defeats and setbacks. The result is a film that is cinematically and dramatically powerful, but disturbing and dissatisfying. Who goes to the movies to escape his grind of a life by immersing himself in a much more arduous grind?

Of course, it could have been worse. Feng could have tackled the Cultural Revolution.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

One thought on “Saturday Matinee 2013 035: Back to 1942”

This reminds me I should see Grave of the Fireflies. Animated Japanese take on a similar subject of two orphaned siblings in 1945 Japan..