Category Archives: Weapons Themselves

This classic old Colt Mustang .380, the original Colt knockoff of the Llama pocket-pistol knockoff of the 1911, has seen better days. Can it be saved? A customer brought it to a gunsmith who told the story on Reddit and Imgur (all these photos came from Imgur, and are linked in the Reddit thread).

The old Colt is still functional enough, but it’s fugly. The steel slide and barrel are pitted. The alloy frame is also corroded, and the trigger guard, integral to the frame, is nicked and generally chewed-up looking. Can it look like new again? Click “more” to see!

Sometimes the Worst Gun Wins, and other Lessons from History

In Smith’s The History of Military Small Arms, the author claims to see a parallel between the introduction of the Dreyse Needle Gun and the history of military small arms in general. To wit:

Dreyse Needle Gun with fabric cartridge and projectile showing primer location at projo base. From The Firearm Blog.

When the Dreyse was introduced into the Prussian service it was a “military secret” of the first order. Like most “military secrets” it was a secret only to those naive branches of the military who never seem to be aware of what has been done in their line—those artless individuals with which every country is regularly afflicted, and who strangely enough seem to be nearly always in a position to make policy while submerging the real experts who are present in any army.1

The Dreyse shouldn’t have been a surprise to anybody, as the technology had been patented by a Swiss circa 1830, when the Prussian generals who would command Dreyse-wielding riflemen were subalterns. And while the Dreyse Needle Gun had an edge on the French Chassepot, it wasn’t that big an edge, really.

The edge was that the Dreyse was able to use a metallic cartridge, even though these images show a fabric one (even though the illustration shows it with a fabric cartridge). But in the Americas, Union cavalry was armed almost exclusively with breechloaders, and in significant part with breech-loading repeaters, generally firing fixed rim- or center-fire ammunition, by war’s end. Having the Dreyse gave the Prussians a momentary advantage over the muzzleloader-toting Austrians, who soon thereafter followed such leaders as Britain (with the Snyder) and the US (with the Allin conversion) and rebuilt its muzzle-loaders into breech-loaders.

Here’s another view of a Chassepot, action closed. The stylistic resemblance to the much later Mosin-Nagant repeater is eerie; did it inspire that design?

Out in the real world, small arms development is seldom secret, and when it is, it is seldom kept secret for long. Engineering and science have long been observed to proceed, worldwide, at the same pace, and weapons of war face something akin to the evolutionary pressures faced by animals under natural selection (minus, perhaps, sexual selection, although the natural competitiveness of armies leads to a pursuit of bragging rights and pride internationally that has some parallels, but with much less power).

It is an interesting fact that, when two armies meet in the field, both sides are almost always convinced that their equipment is superior. When it turns out not to be for one side, an even more interesting fact is that weapons superiority is not always, or even often, decisive. No grunt came away from Cuba or Puerto Rico still believing that the .30-40 Krag, selected by the USA over the Mauser because the Krag had a simpler and easier-to-inspect magazine cut off “to save ammunition in combat,” was the superior rifle. Ordnance’s error in prioritizing that, or perhaps in accepting the priorities given to it by the generals, was clear, and the guns were scarcely still before Springfield was directed, although perhaps not in the words of a later Smith & Wesson executive, to “copy the m’f’er!”

Yet, as deficient as the US mix of Krags and trapdoors was vis-a-vis the 7mm x 57 Spanish 1893 Mauser, a technically superior rifle was not enough to make up for the many other technical and tactical deficiencies the Spaniards faced in trying to hang on to their colonies. Weapons are complex enough to present many features and capabilities, and survival-oriented officers and soldiers quickly learn to exploit their system’s strengths and overcome its weaknesses. The Germans learned to fight against the superior mobility of American and Russian tanks; the Allies learned to fight against the German’s better armor and armament. Meanwhile, a “secret” weapon is only secret until it’s used; after that, the enemy knows its effects, and his own engineers and ordnance men can figure out what the weapon was — as every nation’s scientists and engineers are at, to a first approximation, the same level of knowledge. (The classic example of the limited life of a secret weapon is the way the Soviet Union went from ignorance of the potential for a nuclear weapon to leapfrogging US/UK development of fusion weapons in 4 years).

Napoleon’s maxim about the relative weight of the material and the moral in war is as good an explanation as any for the phenomenon: sometimes the guy with the worse gun wins.

Notes

- B. Smith (2013-07-13 00:00:00-05:00). The History of Military Small Arms (Kindle Locations 910-914). Kindle Edition.

Here’s a Good Gun Review

The editors of Shooting Illustrated did something wicked smart — they gave one of those new “guns for gals” to an actual gal to review, but even more cleverly, they gave it to one who was able to appreciate the engineering, not only the feminine colors (wait. How many of the women you know drive pink cars? Not knowing any Mary Kay reps, my answer is ze-ro. Interesting fact, that). But in this case, the designers of the gun, European American Armory (and their production partners, Italy’s Fratelli Tanfoglio) redesigned the firearm around the fact that there is sexual dimorphism in the human species.

Di-what? That means, men and women tend to be different sizes and strengths. While there’s a lot of overlap in the distributions, both the mean and the positions of the tails of the distributions of things like size and strength skew far higher for men than for women. Which is why you’re going to see a woman on an NFL offensive line around the time a man wins the ladies’ gymnastics gold at the Summer Olympics, and Satan stops burning coal because he needs the carbon credits.

Here’s what our distaff, engineering-wise reviewer has to say about the EAA Pavona:

[W]hat sets EAA’s offering apart from so many in the field, is how the company handled the other half of the equation: the engineering side of things. Mechanically, what EAA needed to accomplish was to design a pistol that would be easy for a new shooter—perhaps with small hands and below-average grip strength—to operate, and still have it appeal to more experienced shooters as well. Fortunately, the platform EAA started with was a solid one.

The gun is based on the CZ-75. Back when the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was being stingy with export licenses to the Evil Capitalists, the licensed their design to the Tanfoglio Brothers, whose early pistols were close copies, and whose current pistols are, like current CZs, more in the line of evolved derivations.

The Pavona is a single-action/double-action semi-automatic, with a long trigger pull for the first shot, and a shorter, lighter pull for subsequent shots. My trigger scale only reads to 8 pounds, and the Pavona’s double-action trigger broke just past the end of the calibrated area. The single-action pull broke consistently right at 4 pounds. The double-action pull, while heavy, was not gritty on the test sample, and the single-action pull had minimal take-up and broke cleanly.

It is just stupid-easy to shoot well, especially for a compact pistol in a service caliber.

Firing controls are also intended to be unobtrusive and snag-resistant. Unfortunately, they are not ambidextrous, although a southpaw might find it easier to activate the slide-stop lever with their trigger finger than a righty would with their thumb. This is a roundabout way of noting the reach to the slide-stop lever is a long one. I

The safety was easy to use and fell naturally under the thumb as the pistol was grasped. Further, unlike a 1911, the Pavona’s slide can be worked with the thumb safety on. That’s a good thing, because it means administrative chores like unloading the handgun or taking it apart for cleaning can be accomplished with the hammer cocked—so the shooter doesn’t have to fight the resistance of the mainspring while running the slide—and still have the safety on as an added layer of precaution.

That’s a CZ-75 feature, as is the ability to carry cocked-and-locked. If you carry cocked-and-locked, why carry a DA pistol? In our case, it’s for a second strike at some Third Worldian primer. The rest of you, keep toting those 1911s. The tradeoff is, as our reviewer notes, that you don’t have a decocker. Some people prefer a decocker to a safety (like in the Beretta 92G). Some want both as independent controls (hence, the fans of SIG’s service pistols). Some of us just live dangerously and point it at the dog while dropping the hammer with our thumb on it (just kidding! No dogs were harmed, or even threatened, in reviewing this review).

Conscious of the needs of new shooters or those with less grip strength, the folks at EAA took a two-pronged approach to remedying this potential pitfall. [The Petter rails-inside-frame design leaves little freeboard for grasping the slide to operate it — Ed.]

First, the company reshaped the serrations on the slide. Despite appearing cosmetically pretty with their shallow, scalloped cuts, when I gripped the slide, I was impressed by the purchase they afforded. There was no problem getting a sufficient grip, even with a thumb-and-forefinger pinch instead of my preferred over-the-top, whole-hand grab.

Another aid built into the handgun is the use of lighter recoil and mainsprings. The reduced-power mainspring (which is accompanied by a heavier firing pin to ensure reliable ignition) also makes it easier for those with less grip strength to cock the hammer before racking the slide.

You know we are going to tell you, especially the chick yous, to go and Read The Whole Thing™. It’s also a pretty good example to illustrate the kind of stuff to cover in a review. Things like:

- What’s special about this design?

- Who is it best suited for?

- How does it compare to a few guns everybody knows (or thinks he knows?)

- When you shot it, and it didn’t jam, exactly how many rounds are we talking about?

Finally, a review has places for both subjective impressions and cast-iron facts. An extra plus in this review for trying to verify some of the manufacturer’s specifications. Sure, the manufacturer says it weighs this, has a trigger pull of that, and holds so many rounds in its magazine. I greatly prefer reviews where they verify these factory numbers. The ugly fact is that the numbers that come in the press packet (for those firms turned-on enough to have a press packet) come from the marketing department and they may have nothing but a nodding acquaintance with the numbers the engineering department is using when they QC the guns.

So we always like it when a reviewer gets the trigger gage out and that sort of thing. This was a good review. We liked it. We’re not the target demo for the gun, but we know people who are. And she’s dead right that the gun-store guys recommending snubby revolvers to women as EDC guns need to reexamine their preconceptions.

Oh, did we say who the reviewer was? Tam of A View From the Porch, one of the folks who made gun blogging look so easy that we followed ’em in. As we close in on three years, it’s a damn sight harder than we expected….

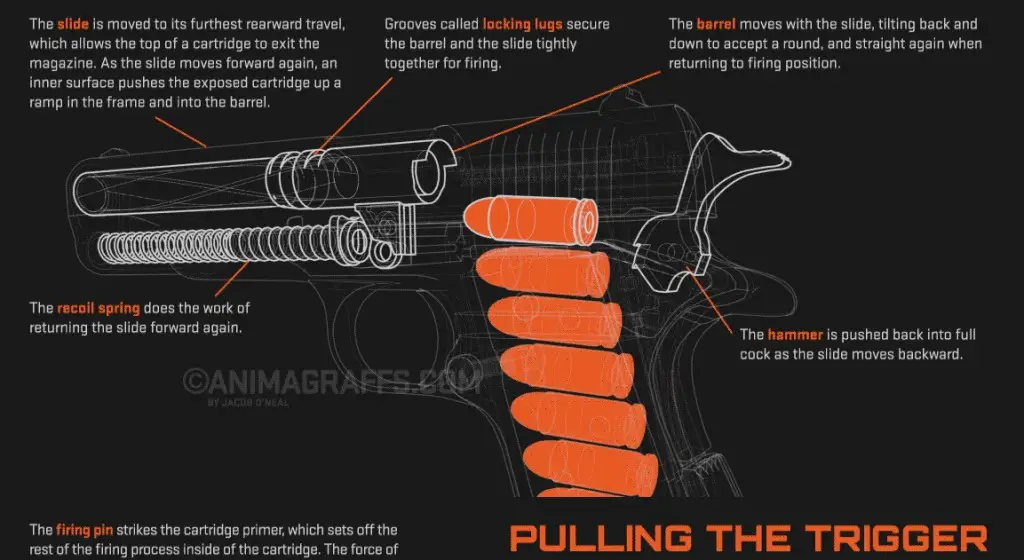

A cool 1911 graphic

We saw this blurbed at Instapundit:

The full thing by artist Jacob O’Neal is something you have to see. Because as cool this is, even clicked-to-embiggen, this is just one small part of it, as a static graphic. The real thing offers several views, and is animated.

Boy. Sure wish we’d had this back in Weapons School, when two of us ran a study hall late into the night to try to save the guys who had been recycled from the class before us. (We did, but it was hard work — mostly by them, we just happened to be college boys with good study habits who could help out).

Go to his animations site, animagraffs.com and enjoy Jacob’s artistry. Along with the gun he’s got jet and piston engines and a tarantula. Then come back, hear?

Back now? Was that 1911 animation cool, or what? So, now go see the animated infographic he did for SilencerCo some time back. (And all you 1911 bashers who wanted a Glock, guess what’s hosting the SilencerCo Osprey in the graphic?)

Guy’s a talented artist. Some website looking for differentiation ought to commission him. (We don’t think we can afford him without crimping the toy budgets).

Colt M4LE Model 6921 Unboxing

Objective: build the best possible transferable replica of an Afghanistan, early war, Special Forces carbine. Specifically the one we toted around Kandahar, Bagram, and on Operation Roll Tide with the 3rd Battalion of the Afghan National Army in the Khamard and Madr Valleys of central Afghanistan.

We started with noting what a young(er) WeaponsMan toted around the hills: an early M4A1 to which the SOPMOD I kit came as an afterthought (and because our company was remote from, and in a different state from, Battalion and Group HQ, we didn’t get the whole kit until we returned, because the Group S4 ratholed it and forgot about it. Supply, a most under-appreciated field of endeavor). We figured the nearest we could come to it was a Colt LE M4, as it would have roll marks similar to the combat-carried weapon, and the correct barrel length. We ordered the gun two years ago, and it came quickly to our FFL.

The trip to the workbench was long and eventful. An attempt to set up new trust came unglued, and after a second attempt, we moved forward with an individual purchase. (And yes, that means when we get the trust straightened out we’ll have to pay another two bill transfer tax to put it in the trust). Then, of course, ATF fell far behind in approving NFA transfers. They finally got the paperwork after all of our delays in March, 2014; in October, at the 6-month point, we called NFA Branch for an update.

“It’s all good,” the examiner said. “There’s nothing wrong with your packet, and it’ll probably be approved.”

“Great!”

“…in January.”

“Oh. Well, thanks. Out here.”

But the examiner underpromised and overdelivered. In November, we got a call with the welcome note: “Your stamp’s here!”

Cool. Two months early! We couldn’t pick it up till this month, so it was like getting an early Christmas gift.

You’ve seen the box; overleaf, there’s a photo-rich set of detail pictures of the carbine after the jump below. The photos are unretouched except for cropping, setting levels, erasing serial numbers (a bit silly, as the guys who scan the net for serial numbers already have this one) and stripping EXIF data.

Continue reading

Gun Oddity: Beretta ‘Combo’

We prowl the halls of GunBroker, half looking for stuff to buy, and half looking for edutainment. This is an example of the latter, in that we never knew it existed: a Beretta 92/96 Combo, which appears to be a factory set with slide/barrel/recoil-spring units in 9mm and in .40 S&W.

Here’s the seller’s blurb:

For sale a Beretta 92/96 Combo, 9mm and 40s&w. As far as I can tell it is unfired, Has the original blow-molded case, original box and all paper work. Barrels and lower are stamped COMBO. Also has extra grips. I will pay for transfer using my local FFL if picked up locally. When I say rare, look around, you won’t find many… IF any! I can send more pictures if you are a serious buyer.

Looks legit to us. The number of these that were produced isn’t visible in any official document, but web pages here and there offer up claims of 500 or 2,500. They come up for sale from time to time, at a premium over a 92 or 96 in equivalent condition.

There is a great deal of modularity in the M92 (etc) design, and the 92 and 96 have identical frames. Therefore, they are convertible simply by swapping complete upper (slide-barrel assembly-recoil-spring), and, of course, the magazine. The recoil spring assembly can be reused, but it’s easier to just have a whole unit to swap. (Also, the recoil spring is probably the single most life-limited part in the Beretta, especially the 96, which has the same spring as the 92 but punishes it more).

There are some limitations on swapping, mostly involving odd-lockwork guns and early (pre-92FS) guns. You can even get some use out of just a 92 barrel in a 96 slide, although the reverse won’t work. However, the newer “Brigadier” slide (the one with the thickened area by the locking block) may have fewer interchange options.

What’s amazing is that guys will still write that you can’t swap uppers from 9mm to .40 on Berettas. This Combo is living proof that Beretta thought you could!

Forgotten Weapons on the Development of the 1911

Through blind luck, the current Rock Island Premier Auction has one of every major variant of Browning-Colt production (even, very low production) pistol from the earliest Model 1900 “sight safety” locked-breech pistol through the 1911, 1911/24 Transitional, and 1911A1 issue pistols. These are three of the oldest: a 1900, a 1900 converted to 1902 (lacking any safety whatsoever), and a 1902 military (square butt and lanyard ring).

Through blind luck and directed expertise, but mostly directed expertise, Ian McCollum of Forgotten Weapons noticed this, and used those pistols — and a Savage 1907, one of Colt’s competitors — to do an impromptu video on 1911 developmental history.

Through blind luck and directed expertise, but mostly directed expertise, Ian McCollum of Forgotten Weapons noticed this, and used those pistols — and a Savage 1907, one of Colt’s competitors — to do an impromptu video on 1911 developmental history.

Except… it’s not least bit impromptu. It’s a real pro job! A half hour plus of awesome gun history. Go thither and enlighten thyself.

And you’ll know what you’re looking at when you encounter one of these, somewhere down the road:

It’s the granddaddy of them all, the “sight safety” pistol that Colt just called the Colt Automatic Pistol — after all, in 1900 it was their first and only one — and that collectors call the M1900 Sight Safety. The name comes from the safety, which was the rear sight: with the hammer cocked, it can be rotated down to block the firing pin.

Normally, we’d embed the video, but we’d really like you to go check out Ian’s presentation, because he also links to each pistol’s page at the RIA auction. At RIA, each pistol’s page also includes links to other vintage Colts.

The Education of Bubba

Here’s a thread in ARFcom’s Build It Yourself forum where the consequences of gorilla (no, not “guerrilla”) gunsmithing come home to roost.

The modular nature of the AR let Our Hero (who just joined ARFcom, and thus dwells in Baby Duck World) assemble a working one first shot:

I built my first AR, took it to the range and it shot great. No malfunctions and great groupings.

Since he titled his thread, “Shouldn’t have messed with [it]” we have already had some foreshadowing of the fact that he did not leave well enough alone, and he didn’t:

I didn’t like the compensator I had though so I bought the standard A2 style flash hider. Put my upper in the action block and into my vise.

Anybody see what’s about to go wrong here? Class? Bueller? Anyone?

We’ll explain. The action block is for protecting the receiver, which although forged 7075 is still only a thin-walled alloy forging, while removing, installing, and especially torquing a barrel. We’re going to emphasize what’s next: action blocks are not for removing muzzle devices. Why not? Well, consider the following as a crude illustration of an AR barrel, with the letter E being the chamber and barrel [E]xtension, the letter A being the gas block or FSB, and the letter D in brackets being the muzzle [D]evice:

[E]]==========A====[D]

So what our novice protagonist did was secure “E” and apply torque at about “D” — 16 or 20″ distant. The barrel is fairly stiff and acts more like a torque tube than a torsion bar, delivering most of that torsion efficiently to the interface between the barrel extension and the upper receiver — where nothing resists that torque but the barrel nut, a little, and the locating pin on the extension which fits into a matching groove in the upper receiver. The locating pin is just for lining the barrel up consistently; it’s not made to bear torque loads, but it is steel and the aluminum alloy slot it rides in is even less able to resist. The pin can bend, but it’s steel. What usually happens is that it springs the upper receiver or cuts the metal of the upper.

What happened here:

The comp came off no problem but the crush washer did not so I got a screw driver gave it a few taps and it came off but damaged the threads on the barrel a little.

Repeat after WeaponsMan, please: “The right tool for the right job.” In fact, write that down. There will be a test. Because all of life is a test — an IQ test.

If you have a crush washer that will not come off, you can thread it off. Don’t worry if you have to mark up its perimeter with pliers or even grind flats on it to get purchase with a wrench, because then you’re going to throw it away. Many fasteners, from the rod bolts on your 350 Chevy to the crush washers on muzzle-devices, are made for one use only.

If you gouge the threads, the right thing to do is to chase them with the right size die. WWBD, though — What Will Bubba Do?

It didn’t look too bad so I put on the new flash hider and it wasn’t too hard to get on I attributed it to the damaged threads but when it got down to the crush washer I had to put some serious torque on it to get it to line up but it went on.

Yeah, ’cause nothin’ fixes threads like cross-threading something else over them. Note also the calibrated Bubba torque wrench, with its precsion torque meter:

- Faint city-boy torque;

- Some torque;

- Some serious torque;

- King-hell torque.

Well, “some serious torque” may not be what the -50 says but the proof of the pudding, etc., so how did Our Hero Bubba do at the range?

at 25 yards it was shooting 8 inches high and 6 inches to the left I knew it would change my POI a little but I had to adjust my sights as far as they would go to zero it again and I know that is not right and I am not okay with that since I didn’t have to adjust the sights at all the first time I went out.

He didn’t say anything about the size of the group changing yet, just point of impact (POI) shift. any muzzle device causes a point of impact shift. Ceteris Paribus asymmetrical devices cause more of a shift than symmetrical ones. The M16A2 flash suppressor is asymmetrical — two “slots” are not milled out, so that no gas escapes in that direction. Those slots should be oriented down, to reduce the amount of dust that’s kicked up when the gun is fired. And so you do have to expect

Quick rule of thumb: a fresh AR upper should work with the windage and elevation near the center of their travel. (A few clicks off absolute center is OK. Most of the way to the end of travel, is not OK). If it doesn’t, Bubba is In Da House.

He’s also violated the Golden Law of Troubleshooting: change only one thing at a time. But for a Bubba, he wises up quickly, and makes one change:

So I took of the muzzle device off and found out I cross threaded it and thought that was the issue so I shot it again with no muzzle device and same thing 8 inches high 6 inches left but still a great grouping its just not where I want it to be.

He found the POI change was the same with the A2 flash suppressor and without it:

i dont think its anything with the muzzle because I shot it with the cross threaded flash hider and with no muzzle device just exposed threads and it shot in the exact same spot for both

Ergo, it wasn’t the A2 cage per se that changed his point of aim. But something did it. Without examining the bubba’d upper, we can’t diagnose it, but our guess is that it was a consequence of either damaging the muzzle crown in his enthusiastic attack on the crush washer, or of torque damage to the barrel assembly or its seating in the upper receiver.

Amazingly — it is ARFCom, after all — he got good advice about what his problem might be, and he began to take it. His responses:

[D]oes this mean I need a new barrel or upper receiver or just take it all apart and re torque everything down to specs?

…I will take it apart as soon as I get home from work and see what she looks like. And my die to re thread the muzzle is supposed to come in today….

Barrel is a gov profile barrel. I learned my lesson and ordered all the correct equipment for my next build….

Ok took it all apart and everything looked fine except for the feed ramps but I could hardly tell they didn’t line up its barely noticeable. Put it back together torqued it all to specs and took it to the range. its shooting in the same exact spot maybe just an inch lower this time but still way off. So I have no idea whats going on

The bit about the feed ramps not lining up tells us he did torque the barrel out of its place in the upper receiver, and the consistent and continuing shooting to a point of impact eight inches out from the point of aim strongly suggests the receiver is hosed, probably where the barrel alignment pin sits.

In the end, he (with a lot of help from the board) came to the understanding that he needed to try a new upper. He lacks the tools, information and skills to inspect his present upper.

Update: I can zero the rifle but I have to adjust the front and rear sights to their extremes which I am not ok with. It is to the point that when I shoulder the rifle I need to remove my cheek from the stock to get a clear sight picture (sure optics would work) but the poi is out of my comfort zone. So I ordered a new upper from Anderson and just my luck the upper is botched and my bcg hangs up about halfway in and my charging handle won’t fit either. So I’m calling them on my lunch break to see what they can do for me.

One suspects that he’ll learn a lot, and in the end have a shootable rifle, but right now he doesn’t. Contrary to what is said in the thread, a displacement of point of aim can come from a damaged crown (without necessarily opening up the groups) but his problem is almost certainly a bubba’d upper receiver.

Eight inches is rather badly out of spec. He can’t even use this thing as a burglar defense gun now, unless the burglars where he’s at are broader in the chest than the skinny meth heads we have around here.

What he should have done, and the things he did right

So, what should Bubba have done, and his rifle would be good and accurate?

He should (as he undoubtedly knows now), have clamped the barrel forward of the FSB (or, with an FSB block, at the FSB) before R&R’ing the flash hider. He definitely should have gotten some advice before putting his back into the wrench on the flash suppressor.

But he did some things right. He asked for help, and most of the comments in his thread gave it to him. He didn’t act on his first impulse, which was to reef on the barrel again, clamping it with a Reaction Rod instead of an action block. (A Reaction Rod is the cat’s ass, but doesn’t address the problem of applying force 15-20″ away from where the barrel’s anchored). Few things can produce more expensive scrap metal faster than impatience at the armorer’s bench.

And a Final Warning

One last warning. Many people take on a flash suppressor replacement as a first attempt at customization. There are a million different kinds to try out. And it’s so tiny, it’s trivial, right?

No, not right. This guy’s results explain why that’s not necessarily a good idea: Just because of part is small, doesn’t mean it’s easily handled, or susceptible to trivial customization. Make your first experiments in AR-smithing on some part of the firearm that is not critical to accuracy and reliability. (That means, not the barrel).

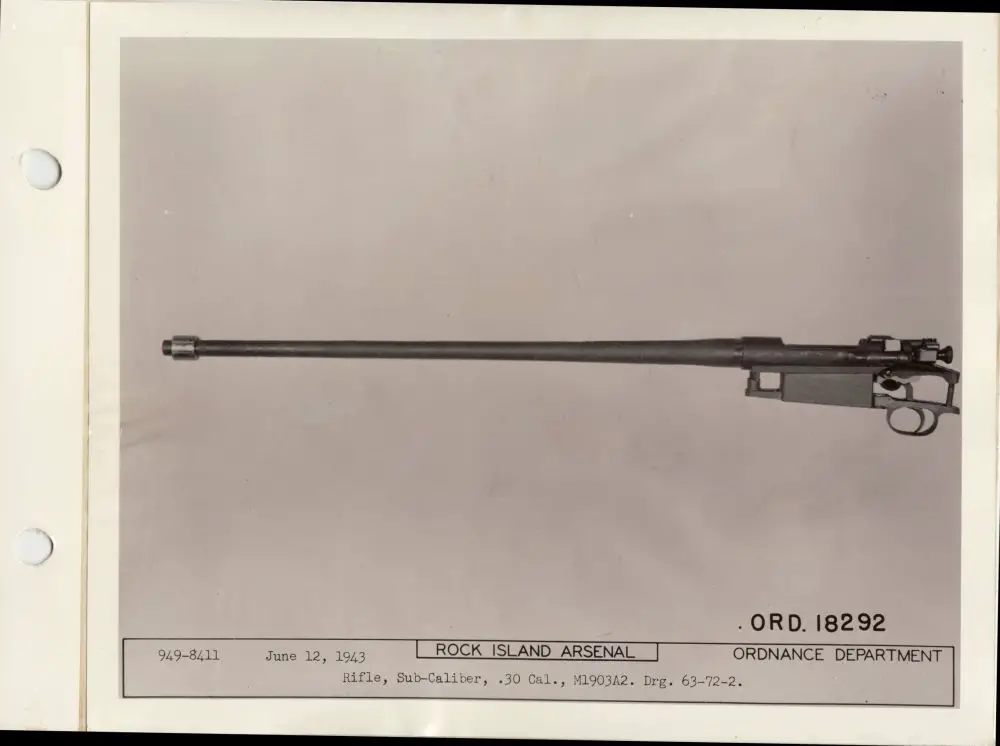

Springfield Rifles: What’s the Difference?

The US model 1903 Springfield rifle was made in five major versions. New entrents to collecting American martial arms sometimes struggle to tell these very similar rifles apart, but actually it’s pretty easy. Here’s a Springfield cheat sheet to take with you to the fun show:

From GlobalSecurity.org. Note that the stock on the A3 is more commonly like the one shown on the A1.

- The US Rifle Model 1903 was originally made for the M1 Cal. .30-03 cartridge, and service rifles were rechambered to the improved .30-06. There were metallurgical problems with early serial number receivers and bolts, and firearms under number 800,000 from Springfield Armory and 286,596 from Rock Island Arsenal should not be fired, because those are the numbers beyond which improved heat treating methods are known to have resolved this problem. (The bolts aren’t numbered, but any bolt that has a handle “swept back” rather than bent at 90º to the bolt axis is good to go).

A few very early models had rod bayonets, and these were mostly converted to Model 1905 16″ knife bayonets after 1905 (at the insistence, we’ve noted, of Theodore Roosevelt) so they’re extremely rare. The rear sight was a ladder sight that went through several iterations, mounted forward of the front receiver ring. It could be used as an open tangent sight or raised and elevated for volley fire to ranges of almost 3,000 yards. A variant of the 03 called the US Rifle M1903 Mark I was adapted for use with the Pedersen device. Most of these were made in 1918-1919 and they wound up issued as ordinary 1903s. They are not especially rare, but make good conversation pieces. Another rare variant (illustrated) used the Warner & Swasey telescope commonly fitted to the Benet-Mercié “automatic rifle” — it had a terrible time holding zero, but that’s what American snipers had Over There.

- US Rifle Model 1903A1 is identical to the 1903, except for the stock, which has a pistol grip.

- US Rifle Model 1903A2 is another extreme rarity: a Springfield altered to be a subcaliber device for conducting direct-fire training on various artillery weapons on small arms ranges. The stock, handguards, sights were removed and the gun could be fitted into a 37 mm sleeve for use in a 37mm gun, or the 37mm adapter could in turn be fitted in a larger-caliber adapter for 75mm, 105mm or 8 inch (203mm) artillery. They were generally made from 1903s and will have the “A2″ notation hand stamped after the 1903 on the receiver ring. A brass bushing on the muzzle, just under an inch (0.994”) in diameter, adapted the bare barreled action to the adapter. A few have the A2 electro-penciled in place, it would take a Springfield expert to tell you if that’s authentic (the example Brophy shows is stamped). Most of the A2s were converted back into ordinary rifles, surplused, or scrapped at the end of the war as the Army had abandoned subcaliber artillery training.

- US Rifle Model 1903A3 is a wartime, cost-reduced version of the 1903A1. Remington had been tooling up to make the 1903, not for the US, but in .303 for the British. WIth American reentry into the war, Remington converted back to making a simplified 1903. The A3 reverts to the straight (no pistol grip) stock, uses a stamped trigger guard, and has a ramp-mounted peep sight like the one on the M1 Carbine. This sight is simpler than the Rube Goldberg arrangement on the 1903, and actually has greater accuracy potential thanks to around 7″ greater sight radius. It is the version most commonly found on the market, and was carried by soldiers in the first months of the Pacific War, and by Marines for longer. Until a working grenade launcher was developed for the M1 and issued in late 1943, an Army rifle squad armed with M1s still had one or two grenadiers armed with M1903A3s and grenade launchers. By D-Day, most combat units had the M1 launchers. Remington (and Smith-Corona) produced 1903A3s from 1941 to February, 1944.

- US Rifle Model 1903A4 is a 1903A3 fitted with a Weaver 330C or Lyman Alaskan 2 ½ Power optical sight. The Weaver sight is 11 inches long and adds a half-pound to the weight of the rifle, bringing it to a still very manageable 9.7 pounds. The Lyman is a tenth of an inch shorter and a 0.2 pounds heavier (the Lyman was very rare in service compared to the Weaver). Both have an eye relief of about 3 to 5 inches. Very late in the war, the M1C came into service, but the 1903A4 was the Army’s primary sniper rifle throughout the war. Note that several vendors have made replicas of the M1903A4, some of which (like Gibbs Rifle Company’s) are clearly marked. All 1903A4s were made by Remington.

There you have it — the main variants of the Springfield Rifle in a short and digestible format.

Three Contenders for the Belt (belt of 5.56 in M27 links, that is)

Here’s Jeff “Bigshooterist” Zimba on belt-fed ARs. You know you’re in for detailed, accurate information and a lot of enthusiasm when Jeff steps up to the camera. You also will get better than the usual YouTube signal-to-noise and filler-to-fact ratios with Jeff on the job:

Jeff’s just slightly mistaken about the original belt-fed, backpack AR-10: it was a pre-Colt Armalite project, and wasn’t picked up by Colt. The video he refers to was a Fairchild promotional video, and here is a version of it. We apologize for the poor quality. The belt-fed version shows up (initially, in Gene Stoner’s hands!) at about 12:30. The weapon’s belt feed does resemble the later Ciener AR-15 conversion, but uses a nondisintegrating belt feed.

Returning to Jeff Zimba’s presentation, his technical points on the Ciener conversion, which is mechanically similar to at least one of the Armalite prototypes, are accurate and informative. It had a number of features that made it rather fiddly, dependent on some design oddities, and generally flawed. Nonetheless, it worked; it could just do with some improvements. Jonathan A. Ciener has been many things in the firearms community, including an innovator; but nobody ever accused him of being keenly attuned to customer sentiment, and the modifications and improvements were left as inspirations to others.

The Valkyrie BSR Mod 1 (BSR = “Belt-fed Semi-automatic Rifle”) is fundamentally an improved Ciener mechanism. The improvements are significant in convenience and function, and Jeff explains them in great detail.

The ARES Shrike is a completely different mechanism that uses a MG-42-like feed mechanism. This gives it some significant advantages over the others. It uses standard links, feeds like every standard belt-fed out there for the last 60-plus years, and can be moved to any standard lower with only one reversible modification (unlike the surgery the Ciener and Valkyrie belts require). Unlike the Ciener and Valkyrie, it alters the AR system to be gas-tappet operated. The operator interfaces with the ARES by a folding, nonreciprocating charging handle on the left side, and an extended bolt release that is the only part that must be changed on a standard AR lower. The ARES also has quick-change barrels, a necessity for high sustained rates of fire.

All of the weapons Jeff demonstrates also can fire from magazines. Ares Defense does make a version of their belt-fed for military and LE customers that lacks magazine feed, the AMG-1 (the version with both belt and mag feed is the AMG-2. There’s also an AMG version with the quick change barrel and tappet gas system, but mag-fed only).

Jeff doesn’t say, but the Valkyrie and ARES belt-feds are still available. Valkyrie Armament also has the modified M27 links, and belt start and stop tabs that are required by its rifle (they should work with a Ciener conversion, but we’d call Valkyrie to check, before ordering).

- ARES AMG Weapons System. (They don’t sell direct. Check out GunBroker or have your FFL order; expect to pay about $4500-5000).

- Valkyrie BSR Mod 1, $4599.

- Valkyrie BSR conversion on your AR, $3599.

Hat tip, the Gun Wire.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.