One of the least covered, but quite serious, insurgencies in the world is that in Mali. The Francophone nation in West Africa has, since its founding, had an uneasy mixture of disparate peoples. The black Africans in the south, a national majority who have dominated Malian politics and institutions, don’t blend with the Arabs and Tuareg of the north.

One of the least covered, but quite serious, insurgencies in the world is that in Mali. The Francophone nation in West Africa has, since its founding, had an uneasy mixture of disparate peoples. The black Africans in the south, a national majority who have dominated Malian politics and institutions, don’t blend with the Arabs and Tuareg of the north.

The Tuareg in particular have been fighting for over fifty years for independence from Mali. The Malian Army is a typical African military: cheerful good intentions met by low cognitive ability all round and an absolute lack of technical and tactical competence. The Malian Joes are willing enough, SF trainers from 3rd (and occasionally 20th) Group have found, but they have a long way to go.

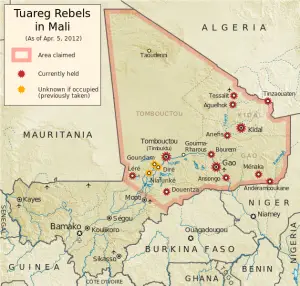

The Tuareg, a nomadic race with a warrior culture, took their show on the road into gun-rich but politically collapsing Libya, and came back armed to the teeth. But they were already armed to the teeth, and after rolling up some Malian Army garrisons, were even more so. The Combating Terrorism Center at West Point reported in the CTC Sentinel:

Although much has been made of the Tuareg rebels’ return from Libya via northern Niger following the collapse of the Qadhafi regime, this circumstance more helped to reinvigorate a stalemated conflict than was itself the raison d’être for the present war. Although Tuareg fighters returned from Libya with fresh stocks of small-arms, ammunition, fighting vehicles, and anti-aircraft weaponry, they also accessed weapons stockpiled from previous outbreaks of political violence and raided arms depots abandoned by retreating Malian troops. A press report described the Malian army weapons acquired by AQIM in Gao as a “vast cache.” (This report ran in AFP on 27 May 12 — WeaponsMan Eds.)

There is evidence that the third source of weapons—those that rebels either never surrendered in previous bouts of secessionism or gained in the years leading up to the 2012 war—also likely forms a significant amount of arms in the current conflict. Ensconced in the rugged Tigharghar Massif due south of the Algerian border, Tuareg rebels then led by Iyad ag Ghaly and the late militant leader Ibrahim ag Bahanga began as a movement called the Alliance for Democracy and Change (ADC) on May 23, 2006, when it mounted attacks on army garrisons in Kidal and Menaka in which they acquired a large trove of weapons.

Another foreign policy website attempts to place the Tuareg rebellion in a historical context here.

The rebels refer to their separatist homeland as “Azawad,” but are divided between nationalist and jihadist-Salafi groups. The balance of power recently shifted when the leader of the largest nationalist group, the Ansar Eddine, became radicalized and now supports extremist Wahabbi/Salafi islam. That leader is the above-referenced Iyad ad Ghaly. This group (sometimes transliterated as Ansar Dine) has also fought with the secular, or at least less-Islamist, Tuareg rebels, the MNLA.

Ad Ghaly’s conversion opens up yet another source of logistical support, including financial and weapons: the world network of Islamic terror financiers. Funds donated expressly for terrorist support make up only a percentage of the haul. A large percentage is donated at mosques worldwide as alms, ostensibly for the poor. Almsgiving is obligatory for faithful Moslems; it is one of the five pillars of Islam. Diversion of these funds to jihad happens at several levels, and is rationalized several ways. Many of the alms givers are comfortable with the notion of their donations spreading the faith, means notwithstanding. Others have been exposed to skillful and pervasive jihadi propaganda. These messages depict terrorist groups as plucky resistance fighters seeking to overcome oppression of the faith.

Mali government troops in their Land Rover match the PKM and raise the stakes: M2HB. Nice guys, but if they can’t exploit the political and ideological faultlines between the factions of their enemies, they could finish last.

Along with arms funded by jihadi auxiliary networks, there is also the possibility of state sponsorship, although no sign of such for Ansar al Eddine or the other Malian groups has yet appeared. In the past, nations as diverse as Egypt, Jordan, Libya, Pakistan and Iran have provided arms directly to Islamist irregulars. Pakistan and Iran have factories which have in the past produced sterile, deniable weapons for insurgent and terrorist use.

We can expect to see more of the Malian rebels in the news. One feature of Islam, of course, is its iconoclasm, in the literal sense. With the rebels in control of the ancient seat of learning at Timbuktu, they have embarked on an orgy of destruction of tombs and shrines (a feature of Sufi Islam that Wahabbis consider shirk or polytheistic idolatry) and have threatened to destroy the libraries of early Islamic documents there.

In an apocryphal tale of the burning of the Library of Alexandria, a Moslem warlord is alleged to have said: “If the books there contain the same information as is in the Koran, they are redundant: burn them. And if they contain information that is not in the Koran, they are heresy! Burn them.” Ansar Eddine leader as Ghaly is reported to have said something eerily similar about the ancient manuscripts of Timbuktu.

So to recap, where did the Malian insurgents get their guns:

- From stockpiles kept since previous unrest;

- From the collapsed military of a failed state next door;

- Battlefield recovery from defeated or deserting government troops, and;

- From abandoned or uncontrolled government arsenals. There are also two other possibilities, which we’ll call

- (speculative) purchased with jihad donations; and

- (speculative) presented by state sponsors of terrorism.

There are many paths by which motivated people can arm themselves. Guerilla logistics are sufficiently flexible and resilient that a wise counterinsurgent attacks not the easily replaced secondary targets of arms, supplies and other logistical nodes, but the primary target: guerilla motivation.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.

2 thoughts on “How do Guerillas Gun Up? A Case Study”

We’ve been looking at this for some time. The gear is Libyan and has been moved south of the border by Muammar’s bedu and tuaregi mercenaries after the revolution, who are now trying to reestablish the ancient fiefdoms. Further fighting between tribal warlords and Al Quaeda offshoots likely.

Some of it’s from Libya, sure. For some strange reason these dictators arm themselves to the teeth, and so when they fall there are warehouses full of all kinds of nastiness for the taking. I have the number ratholed here somewhere, but the Defense Threat Reduction Agency has helped persuade various nations to commit around thirty thousand MANPADS for destruction (mostly SA-7s, but also newer Russian and Western guided missiles). Some third world nations whose militaries ought best to focus on internal security had scores and even hundreds of these things, with inventory controls so lax as to be nonexistent in come cases.

But along with the Libyan arms are many other sources. The Tuareg have been armed with something since their time of legends.