Category Archives: Historical Places

This morning, a steady drizzle fell, and it brought down many of the remaining leaves with it. It remained warm, to a welcome if unseasonable degree, and on our way from one place to another we found ourselves in the Norman Rockwell village of Hampton Falls, New Hampshire.

Like most small towns that existed in 1865, it has a Civil War memorial that has accreted memorials for various other conflicts in the following ages. It was constructed like many other memorials, with an obelisk aspiring to the clouds, and a display of forever-silenced cannon and cannonballs. Unlike many, if not most, such memorials, the cannon and pyramids of shot survived the scrap drives of WWI and WWII. The memorial is located in a small park which is home to various festivals and events during the warmer months, but adjacent to the busy north-south (appropriately enough!) Lafayette Road, named for the French volunteer’s use of the road in the 1820s to visit old friends from the Revolution. Lafayette Road is also US Highway 1, which runs in an unending ribbon of strip malls, motels and neon signs from Maine to Key West. Lafayette Road is on the left in this picture; the yellow building is on the other side of it.

Thousands of people drive by this square every day and never give it a moment of thought.

Of greatest interest to you, dear reader, may be the Dahlgrens themselves. There are four of them, and four pyramids of projectiles, evenly arrayed around the memorial, in the shadow of the flagpole (were there any sun to cast a shadow today!)

The guns appear to be in nearly new condition, although they’re filled with something — probably cement. It’s possible that they were cast at a foundry nearby, and then never delivered to the Navy due to the end of the war. It’s also possible that the Portsmouth Navy Yard had them in storage for fitting out ships. The Navy Yard is a short distance away by road or rail.

The smoothbore Dahlgren guns have a distinctive, coke-bottle shape. They are beautiful machines, and were used in shore defense installations and on seagoing vessels alike. They often had a wooden carriage that resembled the cannon carriage of the Napoleonic wars.

These iron carriages are strictly for display.

Cannon balls may have been obsolete by 1865, but they sure did stack up nice. This pyramid has layers of 25, 16, 9, 4 and 1 ball = 55 cannonballs total.

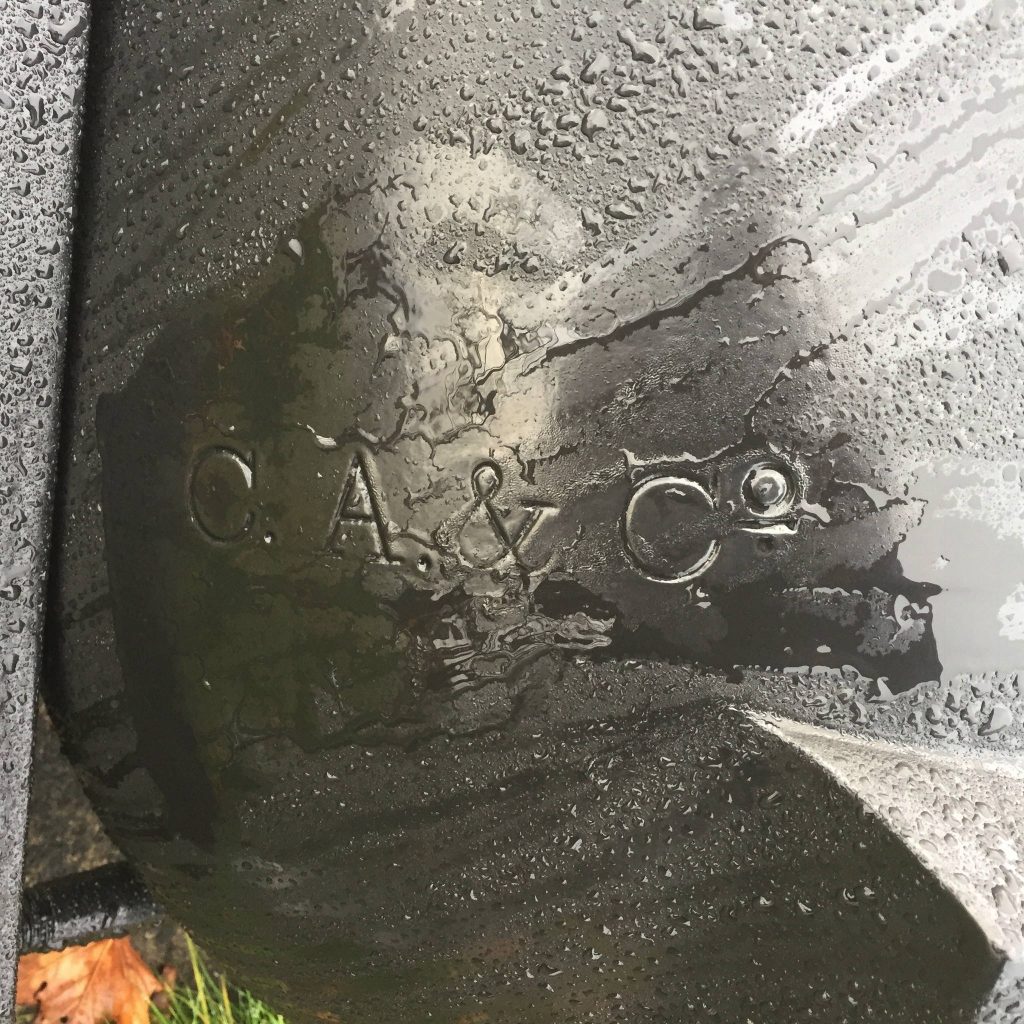

Each Dahlgren Gun is engraved with its maker, its serial number, and its weight, at least to the nearest 5 lb. This one was 4500 lbs. The others were all within 10 pounds plus or minus of this one.

Each Dahlgren Gun is engraved with its maker, its serial number, and its weight, at least to the nearest 5 lb. This one was 4500 lbs. The others were all within 10 pounds plus or minus of this one.

Why bother recording the weight? One possibility we can think of is for trim and balance calculations aboard ship. Three guns were cast by “C.A. & Cº,” and on one the maker name was not visible, but might well have been the same.

Civil War Artillery.com has a useful page about cannon manufacturers, which breaks out this abbreviation as follows:

Cyrus Alger & Co.: Cyrus Alger, who during the War of 1812 furnished the government with shot and shell, in 1817 started South Boston Iron company which at an early date was known locally as Alger’s Foundry and later became Cyrus Alger & Co. The Massachusetts firm was a leading cannon manufacturer and when Cyrus died in 1856, leadership was assumed by his son, Francis, who piloted the company until his death in 1864. During the war, both Army and Navy were supplied with large numbers of weapons. The initials “S.B.F.” (South Boston Foundry) occasionally may be found on cannon, but the signature is traditionally “C.A. & Co., Boston, Mass.” or, rarely, “C. Alger & Co., Boston, Mass.”

The Serial Numbers of the gun whose maker was invisible (perhaps underneath, or marked on the muzzle) was Nº 105. The others were Nº 155, Nº 156, and Nº 157. (Without measuring them, these appear to be 32-pounder guns, of which 383 total were made by Alger and several other founders).

This gives some support to the idea that the guns came direct from production or storage, uninstalled and unfired, to the memorial. Since Alger had been casting cannon for almost 50 years at the close of the Civil War, these numbers must be unique to Dahlgren gun production at the Alger firm’s South Boston, Mass. facility.

Today, it is a place where you can see four Dahlgren guns at once.

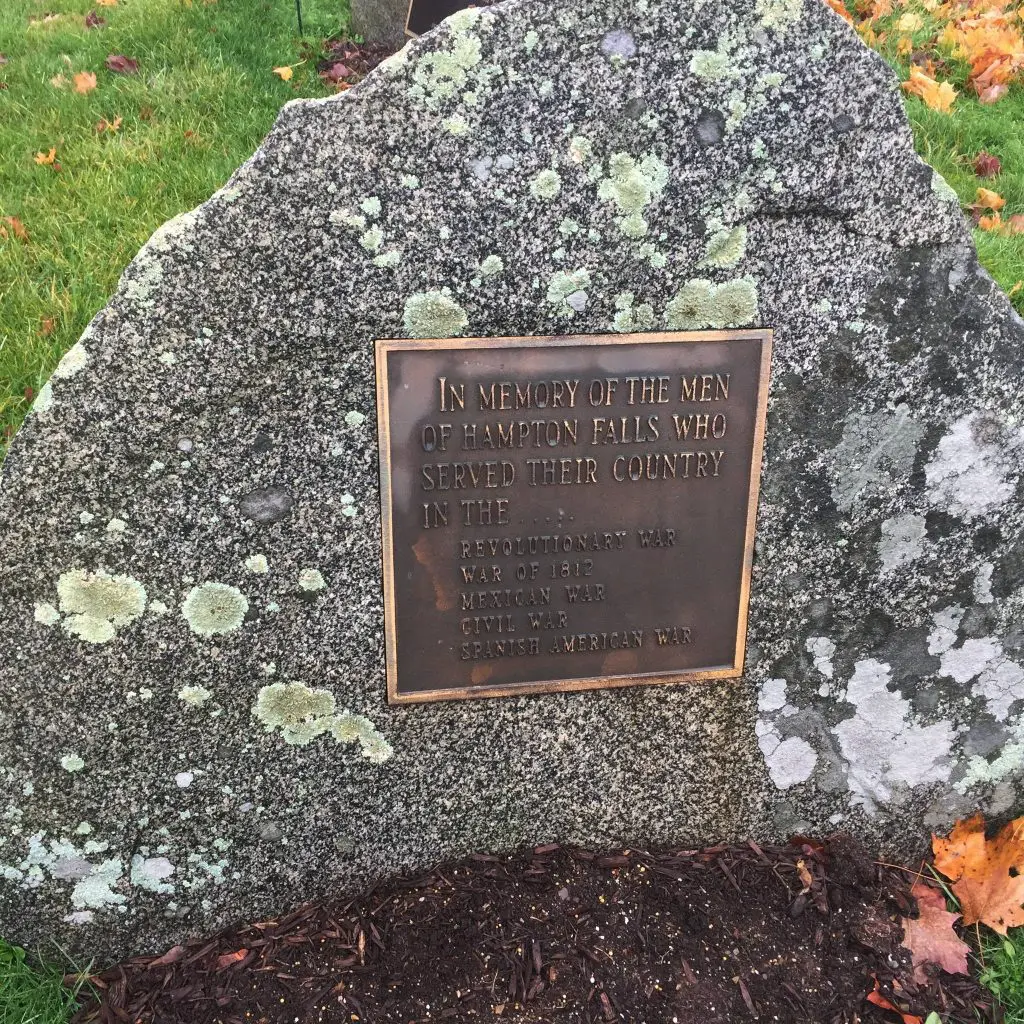

And numerous plaques honor the town’s many veterans, of the nation’s many wars.

Unfortunately, our shot of the Vietnam War honor roll was not successful, nor the one we took of the Civil War honor roll. It was a very different America in 1865 — the names were all English or Northwestern European, and many families sent five to eight men with the same surname to the war.

The town and the veterans’ groups cooperate to tend this little memorial well.

While the Dahlgren Gun served the Union well, and Rear Admiral Dahlgren did, also, he paid a considerable price by giving his design to the nation free of charge. The USA then not only produced some 4,700 Dahlgren guns and howitzers for American used, it furnished the design gratis to various foreign nations. Alger did pay Dahlgren a royalty of 1¢ per pound of guns cast in South Boston for foreign customers, but his widow wound up in straitened circumstances and petitioned the Congress for relief.

Another GI Comes Home from Korea

The responsible authorities, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) never have given up this quest, even as the odds decline, that anyone who knew the deceased in life will be here to get the message of his demise.

Every once in a while they get a DNA hit on remains they only suspected were a certain individual’s. In this case, an Army private murdered by starvation by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army in 1951. Breitbart:

Wayne Minard enlisted in the U.S. Army with his mother’s permission when he was 17 years old but died two years later in a prison camp in North Korea on February 16, 1951, the Bellingham Herald reported.

His mother, Bertha Minard, never forgave herself for letting her son enlist; she died nine months later.

“They say she died of a broken heart,” said Wayne Minard’s great-nephew, Bruce Stubbs.

On Wednesday, sixty-five years later, his remains are coming home to Wichita, Kansas, where Minard grew up, the Washington Post reported.

In Spring 2005, an Army recovery team found a North Korean burial site that held the remains of an American soldier, the Post reported.

Scientists tested DNA samples from two of Minard’s sisters to see if there was a match, and 11 years later, his remains were identified.

The Pentagon released a statement saying that Minard’s remains had been accounted for in September.

Minard “was a member of Company C, 1st Battalion, 9th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, fighting units of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Forces (CPVF)” when “enemy forces launched a large-scale attack with heavy artillery and mortar fire” on November 25, 1950, according to the Pentagon.

He was reported missing in action the next day.

“Minard’s name did not appear on any POW list provided by the CPVF or the North Korean People’s Army,” the Pentagon statement said. But two prisoners of war reported that Minard died at Hofong Camp on February 16, 1951.

“Based on this information, a military review board amended Minard’s status to deceased in 1951.”

Do Read The Whole Thing™. You may find it rewarding. You may also find it interesting to look at press releases related to the identification and homecoming of many Korean and occasional WWII and Vietnam vets the Agency has repatriated and released — 8 men’s remains since the new fiscal year began on 1 October.

A Historic Memorial

OTR, Our Traveling Reporter, is traveling again, and this time he finds himself in a place marked by history. Perhaps you recognize it from the image on the right. A terrible thing happened here — one that remains a magnet for controversy even today .

It’s an open field with a roughly fish-shaped area marked by a yellow-painted anchor chain embedded in the surface. inside, there’s a stone-paved area, and a bronze marker. To get here, you need a military ID — or to join a regular tour, which is closed to all foreign nationals.

Are you ready to guess yet? No? We’ll show you some more images.

To start with here’s another angle. Got it yet?

Hmmm. Let’s try another angle. This looks like a clue. And look at the size of those hangars in the background. They’re behind that white one-story building!

What’s those hangars in the background? Let’s go to the next page for more images, if you haven’t got it yet.

Continue reading

CIA Issues Declassified Bay of Pigs Report — with a Disclaimer

Many years after the event, the CIA had an in-house historian, Jack Pfeiffer, write a five-volume secret history of the Bay of Pigs invasion, and has previously declassified four of the five volumes. The draft fifth volume, which reviews the CIA Inspector General investigation from a 20-years-later perspective, was never revised or approved before the death of the historian drew a curtain on the project. The reasons that the CIA never pursued the completion of this report may be debated. Our opinion is that this volume reflects an opinion which lost out at HQ, the opinion that they key decisions leading to the failure of the operation were not errors made by the CIA in-house staff whom the IG report blamed for the failure, but the ratcheting restrictions on air strikes and air support, which were imposed for political reasons by Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy.

Many years after the event, the CIA had an in-house historian, Jack Pfeiffer, write a five-volume secret history of the Bay of Pigs invasion, and has previously declassified four of the five volumes. The draft fifth volume, which reviews the CIA Inspector General investigation from a 20-years-later perspective, was never revised or approved before the death of the historian drew a curtain on the project. The reasons that the CIA never pursued the completion of this report may be debated. Our opinion is that this volume reflects an opinion which lost out at HQ, the opinion that they key decisions leading to the failure of the operation were not errors made by the CIA in-house staff whom the IG report blamed for the failure, but the ratcheting restrictions on air strikes and air support, which were imposed for political reasons by Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy.

This position was, i n official Washington where the Kennedys are beatified if not sanctified outright, a question of canon law: heresy in the first degree. Yet, the IG report (which the historian is criticising here), took such a partisan pro-Kennedy position as to assume the President (a combat veteran) and Attorney General were unaware of the need for air superiority over the beachhead.

n official Washington where the Kennedys are beatified if not sanctified outright, a question of canon law: heresy in the first degree. Yet, the IG report (which the historian is criticising here), took such a partisan pro-Kennedy position as to assume the President (a combat veteran) and Attorney General were unaware of the need for air superiority over the beachhead.

Referring to the cancellation of the D-Day air strike by President Kennedy on the evening of 16 April 1961, the Inspector General’s survey placed more blame on the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, General Cabell, and the Deputy Director of Plans, Mr. Bissell, than on Mr. Kennedy and Secretary Rusk-even suggesting that perhaps the President “may never have been clearly advised of the need for command of the air in an amphibious operation like this one.” (This, of course, was the position taken by Robert Kennedy during the hearings.) It was not that the President had not been advised, it was simply a case that he and Rusk apparently did not want to risk international criticism of the US.1

Cabell and Bissell, of course, were men whose opinion carried no weight with the Kennedy crowd: unlike JFK and the entire Cabinet, neither was a Harvard man (although Bissell was a Yalie).

SS Houston (and the invaders’ ammo supply) goes up in flames, destroyed by Cuban aircraft preserved by last-minute cuts to the rebel air strikes.

The two principal obstacles to success were RFK and Dean Rusk, and the historian spares Rusk not a bit:

During the meeting in Rusk’s office on the night of 16 April 1961, General Cabell clearly spelled out that unless the brigade aircraft were permitted the strike on the morning of D-Day-particularly the attack on the three air fields which contained the remaining combat aircraft-the Brigade’s shipping probably would be lost and resupply of the beachhead would be impossible. Similarly, at 0430 hours on the morning of the 17th when Cabell went to Rusk’s home and got permission to telephone Kennedy at Glen Ora to ask for naval air cover in lieu of the cancelled air strike, the criticality of control of the air over Cuba should have been obvious even to the slow witted.2

The CIA was required to release this document by legislation; it prepends a cover letter essentially rubbishing the document.

Follow-on consequences: abandoned, out-of-ammo rebels are bound by Castro militia. Castro would sell the survivors of his camps back to JFK — for millions he’d use to export his revolution.

We’re still absorbing the material in this report, but one interesting facet is the “Battle Report” drafted by a former newspaperman, Wallace R. Deuel, based on the story of the landings as told by one of the two CIA case officers with the landing force (who were under orders not to land themselves; Grayston Lynch was a former Special Forces officer, and the other case officer, “Rip” Robertson, was a Marine, both veterans of amphibious combat in WWII).

The IG’s diary contains no further reference to the Deuel report, but a 29 September 1961 Memorandum for the Record from Robert D. Shea-a member of the IG inspection team-read in part as follows:.

In June 1961, Deuel, formerly a well-known foreign correspondent for the Chicago Daily News, was requested to write the story of the invasion. He did this in about three weeks, chiefly by debriefing Grayson [sic) Lynch, who is not a “word man.” The result was a 52-page article entitled “The Invasion of Cuba: A Battle Report,” dated 4 July 1961, of which we have a copy. The request to do this job, which was transmitted to him by Mr. Kirkpatrick, resulted from a suggestion made by Admiral Burke, or another of the Joint Chiefs, in the presence of General Taylor, the DCI, and J.C. K[ing], that the true story should be written and published in order to counteract the untrue accounts that were circulating. A copy of the article was sent to General Taylor, who forwarded it to State and DOD for clearance. State’s reply, under date of 6 September 1961, was that they were against circulating this sort of article and disapproved of the contents. Deuel said that he is glad that the article was thus killed, as he felt that it was somewhat fuzzy, due to the fact that lit was not slanted for any particular magazine.3

One of the great disappointments is that the author’s questions for former CIA Director Allen Dulles, outlined in Appendix D of the report (beginning on p. 156), were apparently never asked and answered. Many of these questions remain.

Some of the rebels’ small arms, most of which were clearly of US military origin. Here, M1919A6 Browning .30-06 machine guns. In the left background, you can see the barrel of a .50 M2HB.

Why would an in-house CIA Inspector General (former operations officer Lyman Kirkpatrick) narrow the focus of his report to focus only on in-house screwups (which were, Pfeiffer agrees, considerable)? Pfeiffer suggests it was a great CIA tradition, to wit, a tawdry Headquarters backstabbing:

Both [IG staffer Kenneth] Greer and [CIA Historian Wayne G.] Jackson indicated that the IG’s survey took the form that it did because Kirkpatrick wanted Bissell’s job. This apparently simplistic view probably was basically at the heart of the matter. By focusing exclusively on internal CIA affairs, the failure of the Bay of Pigs operation could be laid on Mr. Bissell. Had the IG’s investigation taken cognizance of the changes imposed on the plan by the White House and the Department of State, Bissell would lOok to be less the villain. At risk of venturing into psychohistory, a part of the explanation of why Kirkpatrick wanted Bissell’s job is that he believed (perhaps correctly) that if he had not become physically handicapped when his career was in its ascendency, he would have been named DDP before Bissell.4

Kirkpatrick fell victim to polio in 1952, ending any prospects of advancement on the clandestine side of the house; at the time of the Bay of Pigs IG report he’d been IG for eight years and badly wanted the Deputy Director, and ultimately, Director, chair.

But yeah, you can see why the Agency was reluctant to release this, and had to be forced.

The five volumes of the Official History of the Bay of Pigs Operation include:

-

Air Operations, March 1960-April 1961;

-

Participation in the Conduct of Foreign Policy;

-

Evolution of CIA’s Anti-Castro Policies, 1951-January 1961;

-

The Taylor Committee Investigation of the Bay of Pigs;

-

[draft] CIA’s Internal Investigation of the Bay of Pigs.

All these documents, and more besides, are online in the CIA’s electronic reading room. We leave finding them (which can be a challenge in the scavenger’s hoard that is the electronic reading room) as an exercise for the reader. We have provided an OCR’d version of Volume 5 (the one we downloaded from CIA was not OCRd, perhaps they have corrected that by now) for your convenience.

Notes

- Pfeiffer, p. 33.

- Ibid.

- Pfeiffer, pp. 88-89.

- Pfeiffer, pp. 91-92.

Sources

Pfeiffer, Jack B. Official History of the Bay of Pigs Operation: DRAFT Volume V, CIA’s Internal Investigation of the Bay of Pigs.

The Short, Sad Career of USS Lancetfish

Who was the unluckiest guy in the US Navy in World War II? You could make a pretty good case for Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, who was holding the bag when the Imperial Japanese Navy recycle-binned the surface fighting power of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. Naval tradition was served, and Kimmel’s head rolled (career-wise, that is; unlike among our Japanese enemies in that war, in American English that was just an expression).

Who was the unluckiest guy in the US Navy in World War II? You could make a pretty good case for Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, who was holding the bag when the Imperial Japanese Navy recycle-binned the surface fighting power of the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. Naval tradition was served, and Kimmel’s head rolled (career-wise, that is; unlike among our Japanese enemies in that war, in American English that was just an expression).

But we’d like to nominate Commander Ellis B. “Burt” Orr, the first, and only, captain of the submarine USS Lancetfish, SS-296. Orr had been the commissioning-crew engineering officer on the successful USS Rasher, SS-269. For a submarine officer, there can be no greater moment in a career than taking command.

But for Orr, a moment is all it was.

Lancetfish was, in her design and construction, a typical World War II fleet submarine of the Balao class. A submarine was a long-lead-time project; Lancetfish was launched eight months to the day after her keel was laid down at Cramp Shipbuilding Company in Philadelphia.

Lancetfish was, in her design and construction, a typical World War II fleet submarine of the Balao class. A submarine was a long-lead-time project; Lancetfish was launched eight months to the day after her keel was laid down at Cramp Shipbuilding Company in Philadelphia.

Nine months later, the submarine, still a pre-commissioning unit, left Philadelphia under tow to be completed in Boston. Finally commissioned on 12 Feb 45 in the usual ceremony at the Boston Navy Yard, it was having the last things taken care of when, a little over a month later, a dockworker screwed up.

Torpedo tubes have two sets of doors, inners and outers, and you will immediately recognize which is which from their formal names: breech door and muzzle door. Subs of the period were supposed to have an interlock that kept them both from being open at the same time. Perhaps that was one of the things being installed in Boston, but somehow, a worker managed to open the inner (breech) door of #10 torpedo tube, unaware that the muzzle door was already open. He couldn’t shut the door against the rush of water, and scrambled out of the after torpedo room. He might have mitigated the damage by closing the watertight door to the aft torpedo room, but… well, he didn’t. No lives were lost, but Lancetfish settled on the bottom 42 feet below the surface at Pier #8 on 15 Mar 45.

Torpedo tubes have two sets of doors, inners and outers, and you will immediately recognize which is which from their formal names: breech door and muzzle door. Subs of the period were supposed to have an interlock that kept them both from being open at the same time. Perhaps that was one of the things being installed in Boston, but somehow, a worker managed to open the inner (breech) door of #10 torpedo tube, unaware that the muzzle door was already open. He couldn’t shut the door against the rush of water, and scrambled out of the after torpedo room. He might have mitigated the damage by closing the watertight door to the aft torpedo room, but… well, he didn’t. No lives were lost, but Lancetfish settled on the bottom 42 feet below the surface at Pier #8 on 15 Mar 45.

Orr was not aboard; the sub was still in the hands of shipyard personnel; the Navy had yet to fill out her crew. He lost his ship without ever having taken her to sea. Indeed, she never moved as much as a yard under her own power.

If you’re going to sink, of course, there’s few better places to sink than shallow water, pierside, in a Navy yard. But even so, it took eight days to refloat Lancetfish. Eight days in which seawater did its worst with the ship’s electrical, mechanical and hydraulic systems. The Navy being the Navy, both the sinking and the salvage operations were attended by photographers’ mates, and documented to a fare-thee-well.

If you’re going to sink, of course, there’s few better places to sink than shallow water, pierside, in a Navy yard. But even so, it took eight days to refloat Lancetfish. Eight days in which seawater did its worst with the ship’s electrical, mechanical and hydraulic systems. The Navy being the Navy, both the sinking and the salvage operations were attended by photographers’ mates, and documented to a fare-thee-well.

Meanwhile, Navy finance personnel had been estimating her salvage costs, and they came up with $460,000 (about $6.2 million in 2016 dollars). For the Navy, the juice wasn’t worth the squeeze, and Lancetfish was decommissioned the very next day.

Burt Orr survived the loss of Lancetfish. (His old sub, USS Rasher SS-269, actually survived 8 war patrols and the war, too, and even served off Vietnam, before going to the knackers in 1974). But Burt and his sub are likely to retain for all time the unhappy title of shortest command, and shortest commissioned service, in the submarine (and perhaps, in the American naval) service.

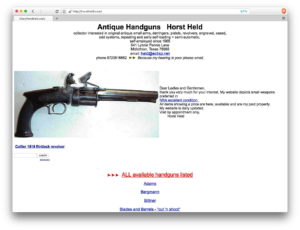

Wednesday Weapons Website of the Week: Horst Held

Why would we make a single dealer the Wednesday Weapons Website of the Week? Well, Horst Held is not just any dealer. Not when you take into consideration the historic significance and quality of the collector pieces Horst is selling. Even if some of them are priced in the nosebleed range, his collection is broad enough, deep enough, historic enough, and packed enough with odd curiosities — like the flintlock revolver currently on the front page — to be an education in itself.

Why would we make a single dealer the Wednesday Weapons Website of the Week? Well, Horst Held is not just any dealer. Not when you take into consideration the historic significance and quality of the collector pieces Horst is selling. Even if some of them are priced in the nosebleed range, his collection is broad enough, deep enough, historic enough, and packed enough with odd curiosities — like the flintlock revolver currently on the front page — to be an education in itself.

We first came across his site while trying to decode the mysteries of the repeating pistols of Weipert (Vejprty), Bohemia. For example, he has two Gustav Bittners in stock. Given the prices he has placed on them, all we can do is look, but he has characteristically included numerous photographs of these peculiar and historic “missing links” between the first single-shot and double-barrel cartridge pistols, and the true semi-automatic service pistol which came along in a few years and rendered the repeaters, operated lever-action (usually by action of the trigger guard), obsolete.

Bittner Repeating Pistol, (7.7mm?) cased with tools, ammo and en-bloc clips, from Forgotten Weapons. We believe this pistol to be in the personal collection of Horst Held.

He also has a page on those strange hybrid weapons that incorporate a pistol or revolver and some kind of knife or sword blade, with an awful lot of examples, not including the rare Elgin Sword Pistol. The Elgin may be rare in absolute terms, but it’s common compared to his examples, like this Dumonthier revolver with a folding bayonet!

And then there’s a Dreyse needle-fire — but it’s not the celebrated Prussian rifle of 1870, but a double-action needle-fire revolver.

But there’s far more here than just that. If you can look at this site and not learn anything, we’ll be very surprised — “By the heathen gods that made ye, you’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din.”

And if you look at the site, you’ll almost certainly be entertained. You may not want to spend thousands on exotic antiques, but you’ll marvel at the ingenuity that went into some of these artistic creations, even as you wonder at the thought processes of the designer who thought it might be practical.

Hand Work in Making 1903 Springfields

During World War I, the national arsenals kept manufacturing the M1903 rifle, while industry was asked to manufacture the M1917. The arsenals decided to document their manufacturing processes anyway, just in case… and the process was published in a book, postwar, by Fred Colvin and Ethan Viall.

While the title of the book is United States Rifles and Machine Guns, it’s almost entirely about the manufacture of the 1903 — part by part and process by process. One gets the impression that the arsenals didn’t actually have a really systematic set of process sheets before someone asked them to make them up for war production; that before that request, this was all tribal knowledge contained in the foreheads of foremen and minds of machinists.

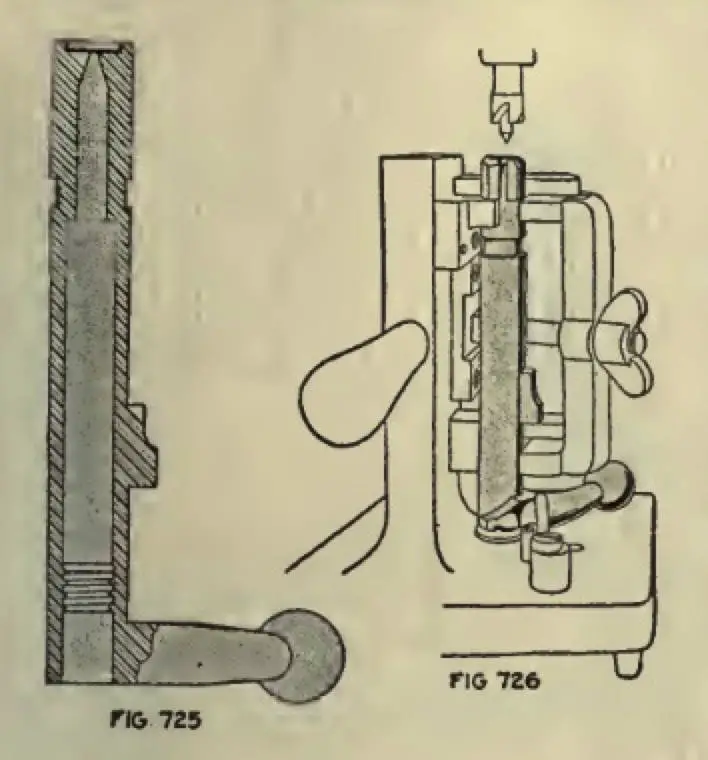

The sheer complication of 1903 production is one take-away from this book, but another thing that really struck us was that this 20th Century rifle, an icon of mass production, was not entirely produced by machines. Along with many machine setups and many trick jigs and fixtures, there are significant hand operations. Here’s one example. If you have a Springfield (or a Mauser, close enough), pull out the bolt and look at its face. See how the bolt face is relieved or “counterbored,” so that the head of the cartridge case is supported? This Is the two-step operation that produces that counterbore. And while the rough operation is done with a powered drill, the finish operation is done with a hand tool. First, let’s look at the rough cut:

OPERATIONS 45 AND 45½, COUNTERBORING FOR HEAD SPACE, ROUGH AND FINISH

Transformation: Fig. 725.

Machine Used: Pratt & Whitney 14-in. upright three-spindle drilling machine.Work-Holding Devices: Drill Jig, Fig. 726; bolt handle stops against a stop, while clamps are drawn down on body by an equalizer bar.

The bolt is on the left, the jig on the right. We’ve omitted Figure 727, which is a scaled three-view providing more detail the drill jig in Figure 726 and the way it locks in the bolt. It’s obvious that getting this right (or wrong) has serious implications for headspace, which affects safety and accuracy.

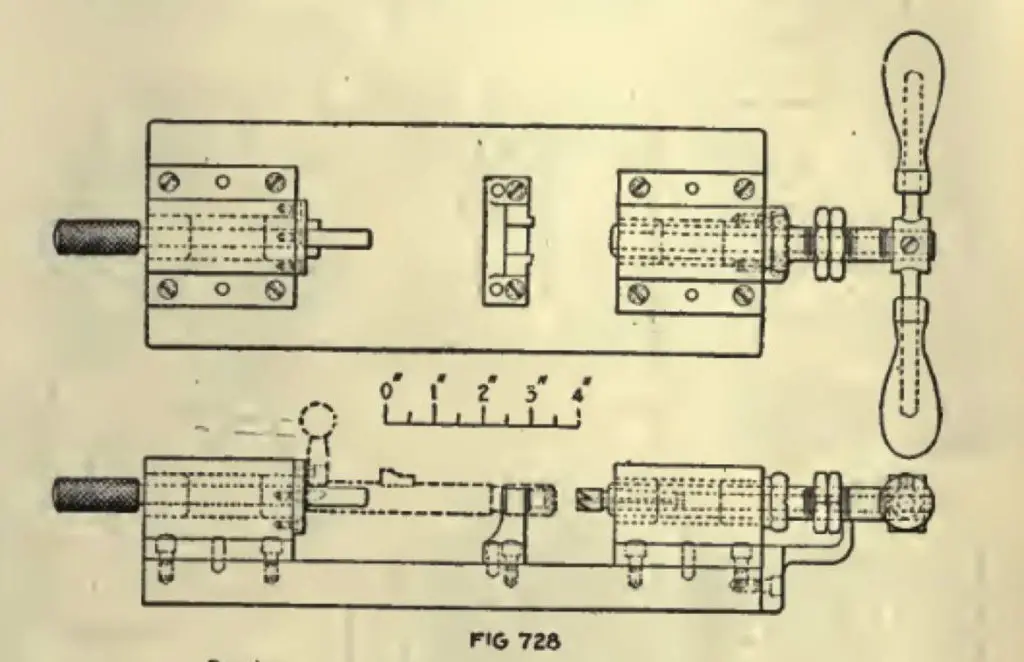

The hand operation’s setup is shown below. It too requires a specific jig. Since here we’re in the forty-something’th operation on the bolt alone, and almost every operation needs one or more jigs or fixtures, the tooling requirement for an early-20th-Century rifle plant is mind-boggling.

Why the hand operation? Our best guess (because the book doesn’t say why) is that, while the Pratt drill press was great at removing a lot of metal, it didn’t have the precision needed (“safety and accuracy,” right?), so a finer cutter in a hand fixture finishes the cut to exact depth and desired surface finish.

As Europe slid into war again, the arsenals were making a new rifle, the US Rifle M1. One suspects this book was the guide for industry as they, once again, produced a version of the 1903, this time with countless manufacturing simplifications. Many manufacturing processes were simplified (and more hand operations eliminated) as the war replaced and supplemented prewar craftsmen with wartime hires longer on enthusiasm than experience.

Incidentally, for the set-up seen here, the book even shows how the cutters and pilots are made, and their dimensions. (There are separate rough and finish cutters). It doesn’t show all the gages that must have been used by both the set-up men and operators of the machinery, let alone the inspectors.

It does show enough that you could probably set up your own Springfield factory and do it exactly the way they did it back in 1917 — if you could find a supply of 1917 Connecticut River Valley gun-industry craftsmen to make all these cuts for you. And if you could get some billionaire to fund you. (Well, there are two famous billionaires competing for the same job right now, one or the other will be looking for opportunities in a couple of weeks). Good luck!

A Scientist, a Fort, an Improvised Measurement

At the climatology blog Watt’s Up With That, guest blogger Tim Ball has a story of how an obscure fort in remote Churchill, Manitoba on the west coast of Hudson’s Bay became the avenue for a scientific competition between France and the British Empire that shaped the world by validating Newton’s Law of Gravitation — or would have done, if the damnable instruments worked. A key player was a British scientist of unprepossessing background:

At the climatology blog Watt’s Up With That, guest blogger Tim Ball has a story of how an obscure fort in remote Churchill, Manitoba on the west coast of Hudson’s Bay became the avenue for a scientific competition between France and the British Empire that shaped the world by validating Newton’s Law of Gravitation — or would have done, if the damnable instruments worked. A key player was a British scientist of unprepossessing background:

William Wales (1734 – 1798), was born in Yorkshire to working class parents. He moved to London and married Mary Green, the sister of astronomer Charles Green.

He obviously showed mathematical ability because in 1765 he entered the employ of the Astronomer Royal, Sir Nevil Maskelyne. He began work on one of the two major scientific challenges of the day, the accurate determination of longitude. However, that was to become interlinked with the other challenge, testing of Newton’s Theory of Gravitation, published in 1687.

via Scientific Integrity is Constant Challenge: A Classic Historical Example | Watts Up With That?.

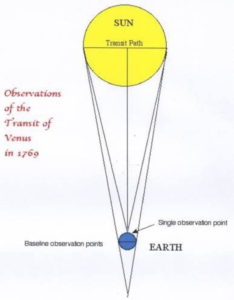

There were several possible ways to do this, and the way that Sir Nevil proposed, Wales didn’t think would work. He got assigned to do it any way — he would go to Churchill, and on the other side of the world, explorer Captain James Cook would be in Tahiti, and they would observe the transit of Venus across the Sun, timing it with precision chronographs, and then by application of trigonometry, they’d have the missing ingredient to plug into Newton’s law of gravity.

There were several possible ways to do this, and the way that Sir Nevil proposed, Wales didn’t think would work. He got assigned to do it any way — he would go to Churchill, and on the other side of the world, explorer Captain James Cook would be in Tahiti, and they would observe the transit of Venus across the Sun, timing it with precision chronographs, and then by application of trigonometry, they’d have the missing ingredient to plug into Newton’s law of gravity.

Previous attempts by both European rivals had failed; the next window was 1769.

The major reason for the 1761 failure, inadequate instrumentation, was not resolved. Nobody knew this better than William Wales. In a parallel of today’s global warming fiasco, the scientists, who were effectively bureaucrats or relied on sponsorship, believed that political support and more money was the answer. So Wales faced a dilemma, keep your mouth shut and do what the King and his lackeys like Maskelyne wanted, or face incarceration and possibly even hanging.

Wales didn’t think the instruments were accurate enough.

Finally, Wales agreed to take up the challenge, but only after negotiating a generous contract that included provision for his family should he not return….

Wales knew the accurate timing was essential to success. He also knew the problems of producing an accurate chronometer. One was specially constructed, and on the Atlantic crossing, he tested it rigorously only to discover it was losing several minutes every day. It was inadequate.

They took a prefabricated observatory with them and on arrival set it up on the SE bastion of Fort Prince of Wales.

In the Georgian era, Wales couldn’t just send for a new chronograph from the remote wilderness of Churchill. And he couldn’t use the one the Royal Observatory had given him. He was trying to measure an angle that would turn out to be 9.57 milliradians. So what options were left?

He built a sundial. (Image at right). Archaeologists unearthed it at the Fort and it now rests in the Parks Canada museum in Churchill.

The challenge for Wales was to establish some way of determining time more accurately than with his failed chronometer. During the restoration of the Fort, a remarkable sundial was dug up at the base of the wall. They also found an iron spindle that allowed the user to turn any of 24 faces toward the Sun.

Ball and Leslie Ross were able to demonstrate that the sundial definitely was Wales’s: it contains the same exact error that is in his after-action report to Sir Nevil and the Royal Society.

In a 1984 article “Observations of the Transit of Venus at Prince of Wales’s Fort in 1769” I identified the latitude Wales had calculated for the Fort. Leslie Ross, a researcher at the National Museum of Canada, was also doing research on the sundial. He asked where I obtained the latitude. I told him it was the one Wales recorded in his journals. He said the latitude matched his calculations for the latitude of the major sundial face (June 1983 Stone sundial from Fort Prince of Wales. Research Bulletin #193). It was clear evidence that Wales made the sundial because both latitudes were different from the actual latitude by 11 minutes. I was skeptical that a sundial could be better than even a faulty chronometer, but Ross told me it could determine the time to within two minutes, which made it superior to the watch.

And the report itself says something about Wales:

On his return to England Wales … refused to submit his report. He said the results were of no value. The timing was imprecise, and the telescope optics were inadequate. Wales was finally ordered to submit a report that was published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.

We are fortunate he complied because Wales did not waste his time but carried out countless other experiments and made many observations. He brought the first barometers and thermometers, constructed to Royal Society specifications to northern North America. He produced an excellent instrumental record beginning in 1768. This continued after he left because he instructed the surgeon in their use.

In the end, Wales’s imperfect measurement of the transit of Venus was overtaken by better measurements, validating Newton’s law. And he resumed work on his other great challenge, measuring longitude.

Far from being angry with Wales, his peers were impressed with his integrity, and when he resumed work on the longitude problem…

Two years after his return to England, the Board of Longitude commissioned him to sail as astronomer and navigator with Captain Cook. Wales job, in association with William Bayly, was to test Kendall’s K1 chronometer based on the H4 of John Harrison.

These superior chronometers resolved many problems, and Wales is a fine representative of the many nameless scientists who toiled (and still toil) in the shadows, gradually dragging the world of the past into a better informed future. Do Read The Whole Thing™.

These superior chronometers resolved many problems, and Wales is a fine representative of the many nameless scientists who toiled (and still toil) in the shadows, gradually dragging the world of the past into a better informed future. Do Read The Whole Thing™.

And what of Fort Prince of Wales? This may have been its high point. While it had 42 guns and another battery of six more across the Churchill River, its garrison was depleted and construction ceased after 1771. During a French raid in 1782, the garrison comprised only 39 civilians, and the fort was surrendered to the French with no resistance or loss of life, and its structures and goods sacked and burned. The cannons on its walls? They never fired a shot in anger. It’s now a Canadian national park and tourist attraction… for tourists willing to travel to someplace that is still quite remote.

Guerrilla Recruitment Lessons from Greece in WWII

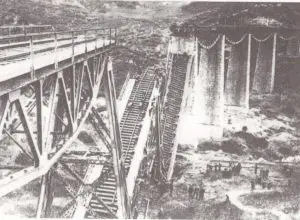

This bridge sabotage on the Gorgopotamos closed the one rail route to Greek ports for six weeks in 1942. The resistance was not directly involved, but afterward, the saboteurs stayed in Greece to form a British liaison mission to the Free Greek underground.

In World War II, there was a moderately effective resistence in Greece, which we’ve discussed here before, and which is the subject of a 1960 monograph (then) sponsored by Special Forces, and now available online at soc.mil.

The resistance supported attacks by infiltrated British parties on German lines of communication to the Afrika Korps, may have tied down German and Italian forces (it’s hard to say; the Axis would have had to guard this flank of their Eastern front anyway), killed some thousands of Axis troops, and harassed the Germans particularly, both in situ and on the point of their withdrawal.

The Allied support to the resistance served several military and political purposes; one of Britain’s most careful balancing acts was fighting the Germans without giving the strongest element of the Resistance, the Communist EAM/ELAS (from its Greek acronyms), enough power to overthrow the country postwar. This was a near-run thing; in the late 1940s, the Communists fought a cruel civil war for control of the ancient land, but were defeated.

Why were the Communists the most effective guerrillas? Their experience underground was one factor, as was their skill at forming coalitions that appeared to be broad, but in which the non-Communists were window dressing or cannon fodder. (Think the Popular Front of the Spanish Civil War, or the similarly-named French government of Leon Blum).

The Communists were effective at recruiting guerrillas, and some interesting lessons were taken away by American scholars studying this war in retrospect (p.19 in the book).

The appeals used by EAM/ELAS to attract persons into its underground apparatus were based on its desire to create the broadest possible underground support structure.

- EAM/ELAS utilized the symbol of universal hatred: the occupiers of Greece.

- It suggested positive action against the symbol of hatred: resistance to the occupiers.

- It completely identified itself with national aims and accused all other groups of being unpatriotic, if not treasonable.

- It took in and gave prestige to repressed elements in the Greek population: in a patriarchal society, women and young people were low on the social totem pole. In the underground of EAM/ ELAS, both groups were welcomed.

- At the same time, the role of men and elders was also upheld, so that the offense to these groups from d above, was held to a minimum.

- Where persuasion alone did not work, EAM/ELAS did not hesitate to use force. Surprisingly enough, persons upon whom force was used appear to have often become faithful supporters of EAM/ELAS.

Let’s look at some of those points in isolation.

1-3. Symbol, Action, Aims

EAM/ELAS was well advised to dissemble about its ultimate aims. It didn’t need fighters for Communism in 1942, it needed fighters against occupation. There would be time to bring them around to Communism later. Anybody who has a political identity toxic to some of the people he needs is well advised to seek a common denominator (and the most effective common denominators are markers of racial, ethnic and national identity). Guerrillas and underground personnel tend to be young risk takers; they will rally to the standard of action, and not the banner of caution. And in defining your war aims, keep your muzzle on the 50 meter targets. Fidel Castro was always a Communist but he didn’t say so until after he won. Why? Because the Communists, too, learned from their defeat in the Greek Civil War.

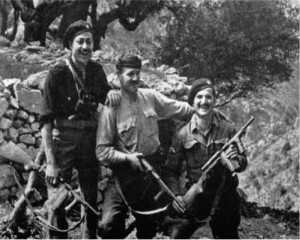

Cretan resistance Andantes. The SOE used weapons supplies as a tool to maintain balance between ELAS and EDES resistance groups. But interrupting weapons flows for political reasons could cause bad blood. Weapons are United Defense UD42 9mm SMGs.

4-5. Recruitment of Shunned Minorities. This is classic SF doctrine, as used in Vietnam (recruiting the Montagnards, Nungs, Hoa Hao and other minorities) and, effectively, in the early period of US opposition to the Taliban (recruiting people from the non-Pathan/Pushtun majority of Afghans). There is always a backlash, as the rural Greeks had to the use of women and youth: in Vietnam, ethnic Vietnamese were alarmed by the USSF taking direct control of units of national minorities, outside RVN military and political control. And in Afghanistan, the coalition of minorities nature of the allied-with-USA Norther Alliance stirred resentment among the nation’s plurality Pushtuns and invited comparison with the Pushtun Taliban.

6. Even forced recruits could become faithful.

That last comment is very interesting and has been borne out time and again in studies of other underground groups, including insurgencies as well as criminal networks. Consider that combatants as disparate as Patty Hearst of the Symbionese Liberation Army, most Local Force Viet Cong, and the vast numbers of Chinese “Volunteers” who threw their lives away against the final protective fires of United Nations troops in Korea, were all impressed, not volunteers. The sailors of the days in which the Royal Navy ruled the waves were largely press-ganged. Consider, even, the performance of units of originally-reluctant draftees at most of the battles since the French conceived the levée en masse as a form of military recruitment.

There’s more happening here than Stockholm Syndrome. In fact, even someone badly used by an organization and opposed to it philosophically can be turned to its ends. (This is very, very often done in espionage, and doing it is the subject of extensive recruitment tradecraft). It is better done by psychological manipulation than by any combination of carrots and sticks, but the carrots and sticks are still useful, just not primary.

An M1 Comes Home

It’s not every day that you hear about a rifle lost on a French battlefield coming back, through the family of the soldier who carried it, to an American museum. But it’s happening with a World War II M1 Garand rifle like the one in the picture — one that was carried by a young American paratrooper in the D-Day invasion.

Martin Teahan was a tough kid from the Bronx, so it’s probably fitting that the story was told through Bronx descendants and in the Bronx Times. And Teahan was one American kid among many whose grit and excellence forever united the American Airborne and the nation of France in the context of martial enterprise, so perhaps it’s fitting that a French Colonel and an American General got involved.

Bronx native Jimmy Farrell is awaiting the return of an M-1 rifle that belonged to his uncle Martin Teahan who served in World War II as part of the 508 Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR).

Teahan, an Irish-American, was killed on June 6, 1944 in Picauville, Normandy after he had been scouting a position.

After his capture, a German soldier killed him.

Farrell, 60, said Colonel Patrick Collet, a French Army Paratrooper commander, contacted his sister Liv Teahan on March 17, St. Patrick’s Day, to let them know the uncle’s rifle was recovered.

“It was the luck of the Irish,” Farrell said with a laugh.

Collet, while visitng a French farmer, had noticed that a rifle the farmer had was engraved with the name “Martin Teahan”.

He then made an effort to contact the family.

Farrell, who served in the U.S. Army from 1974-1977, said that in June he and his wife Monica visited the colonel in Normandy and got a chance to hold the rifle.

“I felt the cold metal of the weapon on my fingertips, and envisioned my uncle, bravely marching forward through enemy territory,” said Farrell.

Afterwards, Farrell said he and his wife got a chance to visit Teahan’s grave site where they met U.S. Army Chief of Staff General Mark Milley.

Farrell, now a resident of East Brunswick, NJ, said his uncle’s south Bronx roots played an important part in Teahan’s toughness.

Teahan, like many in his day, cheated his way into the paratroopers. He joined underage with a forged parental signature.

Farrell intends to donate the rifle for display at the 82nd Airborne Museum or at the Pentagon. It’s a good story; go Read The Whole Thing™.

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.