Afghanistan, 1980-something. A Soviet tank unit visits a brutal reprisal on a Pashtun mountain village north and east of Kandahar. It’s a scene of casual barbarity and calculating murder. The villagers fight back with rifles — mostly old Lee-Enfields — grenades and a single recoilless rifle. One resister is made an example of, crushed under the treads of a tank after his capture. The men of the village are killed or driven into hiding; their few fatal blows against the armored Russian beasts don’t affect the outcome one iota. The women throw rocks at the tanks, without effect; the Soviets don’t even bother to kill them.

Afghanistan, 1980-something. A Soviet tank unit visits a brutal reprisal on a Pashtun mountain village north and east of Kandahar. It’s a scene of casual barbarity and calculating murder. The villagers fight back with rifles — mostly old Lee-Enfields — grenades and a single recoilless rifle. One resister is made an example of, crushed under the treads of a tank after his capture. The men of the village are killed or driven into hiding; their few fatal blows against the armored Russian beasts don’t affect the outcome one iota. The women throw rocks at the tanks, without effect; the Soviets don’t even bother to kill them.

After poison gas and poisoning water holes and wells, they shoot ’em, stab ’em, and in this case, roto-till ’em.

That monstrous opening introduces The Beast, one of the very few movies about the Soviet nightmare in Afghanistan, a long and bitter war that undermined one of the greatest empires in history, and had a direct role in its dissolution. That history was in the future when The Beast edged into theaters in 1988; the story and events in the movie closely tracked the headlines of the 1980s. But the movie, shot in Israeli locations in a desert remarkably similar-looking to the actual areas it’s supposed to portray, is something else: it is an adaptation of a stage play that didn’t lose its staginess when it grew an outdoors and lost its confined stage.

The tank and the mountain setting notwithstanding, it’s really a movie about fraught personal relationships: those within the tank’s four-man crew, those within and among the pursuing mujahideen, and those where the two sets intersect.

Acting and Production

The actors are proficient journeymen and do what they can with an overwrought, often wordy script. Three roles are very important: Jason Patric as Konstantin Koverchenko, George Dzundza as tank and unit commander Daskal, and Steven Bauer in a typically good turn as Afghan villager Taj Mohammad, who’s forced to become Khan before his time by the death of his father.

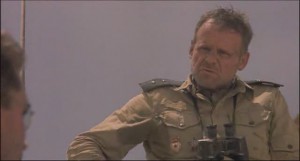

Daskal is the weakest of the primary characters, not because there’s anything wrong with Dzundza’s performance, but because the script gives him such crabbed and meager scope. Daskal is almost cartoonish in his singleminded cruelty and drive; Dzundza delivers it, but it’s all he’s got to deliver. A story about his childhood, in which he killed German tanks as an 8-year-old at Stalingrad, becoming a celebrity called “Tank Boy,” seems an ill-fit with his present role as a company or battalion commander of an armor unit. But then the talky script often tells instead of shows, and when it does show: i.e. Russians poisoning a waterhole, to underline that they’re bad guys, or gunning down a friendly out of sheer paranoia — it overdoes it.

The conflict between Koverchenko and Daskal is mirrored by conflict between Taj Mohammad and another Afghan leader, even as the main conflict is supposed to be between Taj and the other muhajideen on the one side, and Koverchenko and the Russian tankers on the other.

Despite the script’s awkwardness, the actors do what they can. Some of the bit players are especially good, also. Eric Avari, an Indian-American actor of Parsi descent, is especially brilliant as Samad, an Afghan officer who tries to reconcile his Pashto heritage with his commitment to modernity and “scientific socialism.” The script, again, undermines his understated performance by all but hanging a “tragic figure!” sandwich board on the guy.

Apart from the absence of a script doctor’s tender ministrations, the movie has a few other telltale signs of a low budget. In the sweeping tank attack, for example, we seldom if ever see more than two moving tanks. And a key ingredient in the story — the conflicts, alliances, and realliances among the characters — often rings false. The characters act in ways that seem inexplicable without the dead hand of a writer making them do irrational things to build on-screen conflict or suspense.

But before we beat up the writer too badly for his stagey dialogue, let’s mention a few things he gets right: the power of the code of Pushtunwali, which is central to the plot of the story in its balancing of badal, revenge, and nanawatai, hospitality. For Hollywood reasons, the code is simplified, but it’s accurate. The script also emphasizes the eternal nature of Afghan culture with quotes and themes lovingly lifted by the greatest poet of the Northwest Frontier, Kipling. Only occasionally is the reader beaten over the head with this, as when a Kipling quote leads in to the movie; more often is so subtle as to be subliminal, as in the way the relationship of Taj and Konstantin tracks those of some of Kipling’s characters.

On the plus side of the ledger, director Kevin Reynolds knows how to exploit the suspense, however created; and how to shoot action. The climactic battle between the tank and an RPG team is well-paced enough to induce anxiety in a viewer (even if he has little love for either set of characters — can’t they both lose?). One way Reynolds does this is to cut between close-up shots and a very distant view that shows both the tank speeding along the road, and the muj rocketing over a mountain on gazelle feet to cut the off. It’s a “race to the crossing” for the late 20th Century.

Accuracy and Weapons

There are two facets to the accuracy of The Beast: the props and the action. The action is, in places, quite unbelievable. There is a key moment when the action of women muj turns the tide of battle — something that is so foreign to Pushtu tribal culture that it’s starkly unbeliavable.

There are two facets to the accuracy of The Beast: the props and the action. The action is, in places, quite unbelievable. There is a key moment when the action of women muj turns the tide of battle — something that is so foreign to Pushtu tribal culture that it’s starkly unbeliavable.

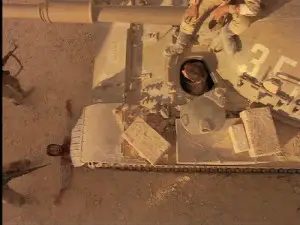

On the props, the producers tried. Perhaps the key prop is the tank itself: a generic T-55, the kind scattered around the world by Soviet influence-building approaches. Sometimes Reynolds shoots inside the tank with a widish-angle lens, emphasizing the cramped quarters, as the tankers run through realistic (if NATO-terminology) crew drills in combat. The muj refer to it as The Beast, and compare themselves to David hunting Goliath.

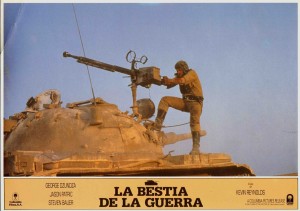

A foreign poster shows the fake DShK from its most convincing angle. The tank is itself almost a character in the film.

The tank’s flexible gun is supposed to be an DShK, but it isn’t; it’s a Browning cosmetically hacked to look Russian. The Russians do have period AKMS rifles, but the Afghans are armed with an improably wide range of weapons that includes not only AKMs, jezails and Enfields, but also Israeli-pattern FALs. Wait…what? A “Russian” helicopter is a Aerospatiale Super Frelon with a make-up job (the Frelon was in Israeli service during the making of this movie, which is probably how it came to stand in for an Mi-8). And they did show an RPG and an 82mm recoilless rifle somewhat accurately. There’s a hokey scene in which Koverchenko repairs an RPG with parts cannibalized from an Enfield. (Kids, don’t try this at home). The Afghans seem amazed at his mastery of the RPG… which is just silly, if you’ve ever known any Afghan men. Every one considers himself an absolute expert with all weapons, especially if you have the poor fortune to have to train these men who don’t think they need training.

Honest, he’s just dry-firing the RPG-7V in this scene. The movie does show it needs a rocket-grenade to work.

So, the weapons were sometimes right. Two things deserve consideration here, before we beat their accuracy up: first, in 1988 the Soviet Union was still largely a denied area, and its (and its satellites’) weapons exports to the West were de minimis. (Some years prior to this, it had taken a Presidential Finding to acquire comblock weapons for operational use by American special operations forces). So apart from the second thing, the filmmakers might be excused their irregularities. The second thing is that Israel, where they shot most if not all of the film, captured industrial quantities of Soviet arms in 1956, 1967 and 1973. So somebody should have been able to outfight the combatants with the right stuff.

The sights and sounds of guns firing are generally good. Artillery fire and explosions, though, are generally wrong: great Hollywood gouts of gasoline fire.

At least theres no bad CGI — this movie predates CGI.

The bottom line

The Beast is the best movie about Russians in Afghanistan to be set largely in and around a 36-ton tank. With its negative portrayal of not only the mission, but also the men, it must drive Russian Afghantsy to a reasonable first approximation of insanity. We know that former mujahideen hate the way they are portrayed here. (But what other feature tells the story of the Russo-Afghan war at all? Russians and Afghans alike also have problems with 9 Rota). It’s a fast-moving watch, with some cinematic and stage pretensions, which may explain why it has a certain cult-film following these days.

You’ll probably enjoy it if you’re not Russian, a mujahid, or prone to taking movies too seriously. K boyu!

Kevin was a former Special Forces weapons man (MOS 18B, before the 18 series, 11B with Skill Qualification Indicator of S). His focus was on weapons: their history, effects and employment. He started WeaponsMan.com in 2011 and operated it until he passed away in 2017. His work is being preserved here at the request of his family.